No Idea Too Radical: Inside New Orleans’ Dramatic K-12 Turnaround After Katrina

Two decades after Hurricane Katrina forced the reboot of New Orleans' schools, academics and college-going are up, but racial divides persist.

School had been in session for 10 days when Hurricane Katrina made its way up the Gulf Coast and slammed into New Orleans. On Monday, Aug. 29, 2005, the resulting storm surge breached major levees, leaving the city underwater. Only a handful of schools were unharmed.

As they contemplated the road to reconstruction, New Orleans’ leaders knew residents could not come back without schools for their kids. But the district — at the time the nation’s 50th largest, with 60,000 students — was at an inflection point. Official corruption was so rampant the FBI had set up an office at district HQ.

A revolving door of leaders — the Washington Post dubbed it a “murderer’s row for superintendents” — had failed to make a dent in some of the nation’s poorest academic outcomes. Louisiana’s legislative auditor called it a “train wreck,” noting that no one knew how much money the district had.

As to what should come next, no idea was too radical, the interim superintendent at the time, Ora Watson, told PBS.

Radical, indeed. Over the years that followed, New Orleans became the country’s only virtually all-charter school system. Outsiders eager to test their education reform ideas jumped to influence the experiment. School leaders took up the best innovations and joined forces to hammer out solutions to the thorniest issues.

It was the fastest, most dramatic school improvement effort in U.S. history — but one that came with steep racial and cultural costs. Now, on the 20th anniversary of the storm, the schools’ current and former leaders — and we at The 74 — are taking stock.

To tell the story of New Orleans’ dramatic turnaround, we’re focusing on six key data points, based on research from Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance for New Orleans; the Brookings Institution; Southeast Louisiana’s The Data Center; and local school system leaders. They are: academic performance, graduation rates and college enrollment; major demographic shifts in the teacher corps; changes spurred by a centralized student enrollment system; college-going and persistence; the number of publicly funded preschool seats; and the benefits of — and ongoing resistance to — shuttering underperforming schools.

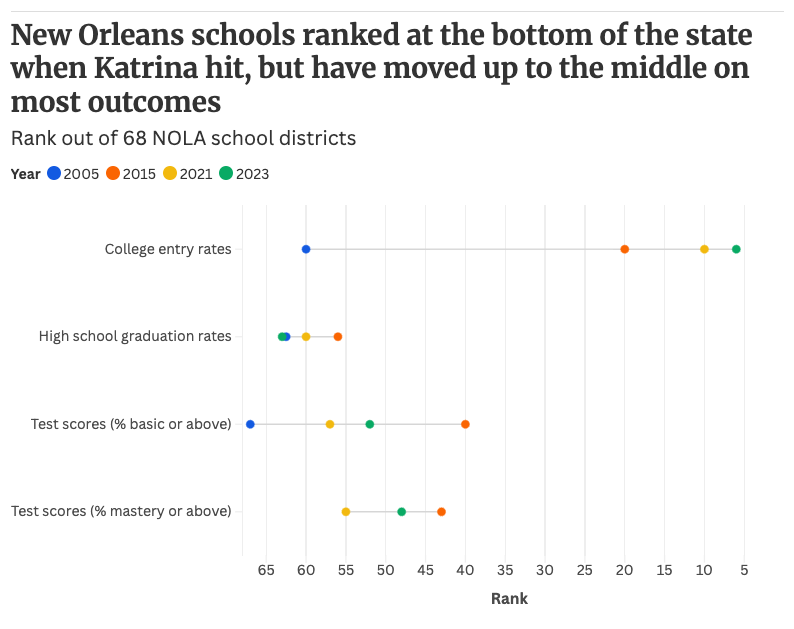

1. Student test scores, graduation rates and college-going rose quickly — but mostly peaked in 2015

Two years before Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana lawmakers voted to create a state-run Recovery School District, which could take over and turn around persistently underperforming schools. It had taken control of five New Orleans schools and converted them to charter schools.

In fall 2005, recognizing the unprecedented scope of the rebuilding needed in New Orleans, the state legislature expanded the Recovery School District’s authority. The agency took over 102 of the Orleans Parish School Board’s 126 schools. Of the remaining schools whose facilities were salvageable, the district turned several into charters and retained control over five.

The schools the district continued to operate directly were exempt from the takeover law because they were academically high performing — in large part because they used admissions tests and other screens to limit enrollment to a majority of affluent and white children.

Big names in the education reform movement leaped at the chance to weigh in on a wholesale reenvisioning of the schools. Over the next decade, the state developed a system that — controlling for demographics and other variables — is credited for rapid growth in academic performance.

Between 2005 and 2015, math and reading proficiency increased by 11 to 16 percentage points, depending on the subject and method of analysis, boosting the city’s schools from 67th in the state to 40th.

High school graduation rates rose by 3 to 9 percentage points, and college-going and graduation rates rose by 8 to 15 and 3 to 5 points, respectively.

Much of that progress is credited to the performance contracts to which the charter schools are held. Those that don’t meet their goals several years in a row lose their charters, which are then given to high-performing operators.

Overall, on state report cards, the school system rose from an F to a C during the first decade. But as Katrina’s 10th anniversary approached, community frustrations with the state takeover boiled over.

Many of the grand experiment’s architects were white and from outside the city. Conversations about flashpoints such as school closures took place in the state capital, Baton Rouge, making public meetings inaccessible to New Orleans families. While some high-performing schools did not hand-pick their students, too many kids lacked access to A- and B-rated schools.

With political pressure to end the state takeover mounting, leaders of the city’s charter school networks brainstormed solutions to some of the thorniest obstacles to reuniting all the schools in a single district overseen by an elected board. Crucially, that meant attempting to make enrollment, discipline and funding — all set up in ways that kept low-income Black children segregated in poorly resourced schools — much more equitable.

Enrollment reforms were already underway. Money, however, threatened to be a sticking point.

Because Louisiana historically gave schools extra funds for students identified as gifted and underfunded services for children with disabilities and impoverished kids, schools that served mostly wealthy students were better funded than those that served challenged demographics.

In 2016, the state changed the formula to make per-pupil funding more fair for children with disabilities and in poverty.

(NOLA Public Schools has since changed the finance system to send schools more funding to pay for services for an array of disadvantaged children, including youth involved with the criminal justice system, homeless kids and refugees. It is now considered one of the most equitable weighted student funding systems in the country.)

Locally forged policies in place, in May 2016 the Louisiana legislature passed Act 91, requiring the Recovery School District to return control of all 82 public schools to the Orleans Parish School Board by July 2018.The law holds the publicly elected board responsible for opening and closing schools according to strictly defined parameters. The schools’ independence in making decisions about staffing, curriculum and the length of the school day is enshrined in state law.

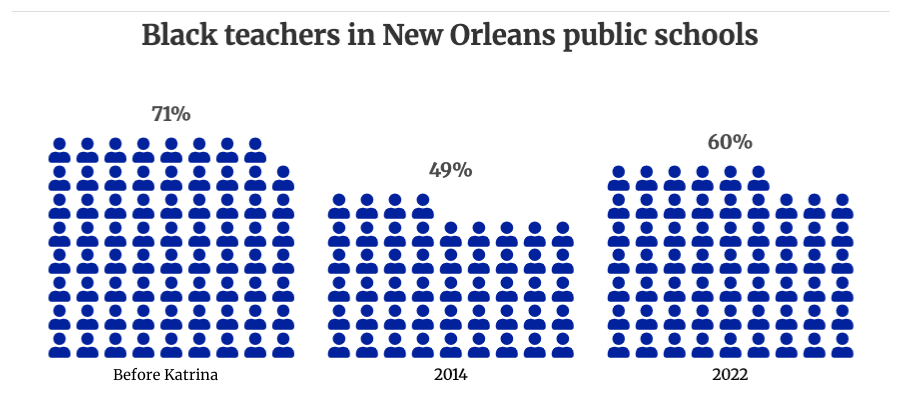

2. A new, very young, very white teaching corps

One of the most persistent, negative narratives about the post-Katrina school reforms is that white outsiders fired the city’s majority Black, veteran teachers and replaced them with an army of inexperienced, mostly white do-gooders from Teach For America and similar alternative training programs.

The actual chronology is more complicated — and rational. Yet it is true that while children are more likely to flourish when their teachers look like them, New Orleans has fewer experienced, certified and Black teachers than it did in 2005.

At the time of the flood, the district was nearing bankruptcy and facing federal corruption probes, and state officials did not send extra aid to help keep teachers — virtually all of them evacuees — on the payroll. In September 2005, the Orleans Parish School Board placed all educators on unpaid disaster leave, enabling them to collect unemployment.

In March 2006, with all but a handful of schools still closed, the district fired all its teachers. One-third qualified for retirement.

According to a 2017 report published by Tulane’s Education Research Alliance for New Orleans, 4,332 teachers were dismissed in the wake of the storm. By fall 2007, half had returned to jobs in Louisiana public schools. A third were working in New Orleans. By fall 2013, only 22% of those fired after the flood were teaching in the city’s schools.

Before Katrina, 71% of the city’s public school teachers were Black. The number dipped to 49% in 2014 and had rebounded to 60% as of 2022, while 70% of students are Black. In 2005, 67% of local teachers had more than five years of experience. In 2022, only 51% did.

As for the influx of young white educators, Teach For America had been sending small numbers of newly minted educators to New Orleans schools for 15 years before the storm. Afterward, the number mushroomed. From 2009-19, at least 20% of the city’s public school teachers were graduates of alternative certification programs. The pace of teaching during those first 10 years proved unsustainable, with many educators citing burnout on surveys probing the causes of increased turnover.

Today, teachers report mixed views on which aspects of their work have improved and declined since Katrina, but a survey of students in grades 6 to 12 finds they are significantly less likely to say their teachers care about them than their peers nationwide.

In recent years, NOLA Public Schools and neighboring Jefferson Parish Schools each have needed a staggering 500 new teachers a year — a recruiting target nearly impossible to accomplish via traditional means.

The number of new educators Teach For America has placed in New Orleans schools has slowed to 30 to 40 a year, says Jahquille Ross, chief of talent for New Schools for New Orleans, the district’s nonprofit policy partner. A training program operated by TNTP (formerly known as The New Teacher Project), teachNOLA graduates 80 to 100 new educators a year.

A former second grade teacher, Ross is in charge of a large-scale effort to bridge the talent gap.

Ross was in eighth grade when Katrina drove his family to evacuate, first to Alexandria, Louisiana, and later to Texas. As a result, during the 2005-06 academic year, he attended three schools. In New Orleans, most of Ross’ teachers and classmates were Black — not the case in his new, temporary schools.

When Ross returned to New Orleans, he enrolled at Edna Karr High School, which had been a sought-after beacon of Black excellence. It’s one of a number of schools known for educating multiple generations of individual families, who enjoy relationships with the same teachers year after year and who return to participate in the city’s fanatically active alumni associations.

An academic top performer before the storm, Ross struggled to satisfy his own high standards as his family moved from place to place. At Edna Karr, Ross was taught by Jamar McKneely, now CEO of the high-performing school network Inspire NOLA.

McKneely, Ross says, “poured it into me,” cementing his desire to become a teacher early. Partway through a degree at Tuskegee University, he reached out to his mentor in search of a student-teaching position. McKneely placed him at Inspire’s Alice Harte Charter School.

“He’s like, ‘Of course you can come,’ ” says Ross. “’But one thing: When you graduate from college, I want you to come teach at Alice Harte.’ ”

Ross didn’t need convincing. “I think about the amount of trauma that I experienced on a day-to-day basis and reflecting on my own growing up,” he says. “I wanted students who look like me to see themselves at a younger age.”

In recent years, Ross has helped create three major initiatives: A $14 million effort to bolster teacher and principal recruiting and retention in six school networks; an $8 million program that pays a living-wage stipend to trainees at Southern University at New Orleans; and educator preparation programs at Tulane, teachNOLA and Xavier and Reach universities.

The third has been by far the most successful. In its first two years, the $10 million program exceeded its goals, bringing in 125 and 231 new teachers, respectively. Two-thirds were educators of color. Year three, 2025, had been equally promising — until the Trump administration canceled the program’s federal grant funding in February. The loss is devastating, says Ross.

“It leaves many organizations and schools to figure out a huge financial gap for the remainder of the year,” he says. “In addition, our educators feel it the most. Between the stipends to mentor teachers or the tuition waivers [or] discounts, it leaves a lot of them wondering where they are going to come up with the money to continue their educational programs.”

Ross has also been instrumental in creating “grow your own” programs that begin training would-be educators while they are still in high school. We profile one such effort here.

3. The OneApp solution

Before the state turned control of the schools back to a potentially politically weak elected school board, New Orleans’ school leaders got together and, competition notwithstanding, hammered out solutions to some of their most contentious, systemwide issues. In addition to the effort to make school funding fairer, most of the school leaders wanted to make enrollment and discipline more equitable.

The high-performing schools not taken over by the Recovery School District had long used admissions tests and other screens to hand-pick their students. One gives preference to the children of Tulane faculty, for example, while others give first shot to students whose siblings already attend.

They were much whiter and wealthier than the rest of the city’s public schools. Just 3% of students in these selective-enrollment schools had disabilities.

As for the schools under state control, the post-storm move to an all-charter system initially created a Wild West landscape for families. Individual schools decided — often without criteria or explanation — whether to accept students who showed up hoping to enroll, and whether a student had too many challenges, including a special education plan. Families were forced to traverse the city, hat in hand, looking for a placement their child might not be able to keep.

For the first few years, expulsion rates in the city’s non-exclusive schools tripled. In 2012, recognizing that educational access was a core civil right, the Recovery School District took away schools’ ability to expel students and had an agency staff member review every proposed attempt to dismiss a child. Expulsions plummeted — fast.

At the same time, the Recovery School District had rolled out a computerized enrollment system that allowed families to list their top-choice schools and, ideally, get matched to one.

Initially dubbed OneApp, the system was touted as a way to give low-income families an equal shot at a seat in the most desirable schools. But in practice, it fell short. Many schools resisted joining the effort, including all the selective-enrollment programs.

As the 2016 date for beginning to return all schools to the Orleans Parish School Board approached, a compromise — disappointing many of the state takeover’s architects — was forged. Selective-enrollment schools authorized by the district could keep their screens but would have to participate in the system or risk losing their charters. It was a weak threat, since high-performing schools generally face renewal only every 10 years, but after the return to local control, expulsions continued to decline. Meanwhile, the number of students with disabilities attending school rose steadily — because of the system and also because the schools were subject to a court decree stemming from a 2010 lawsuit.

Racial enrollment disparities persist, however. A 2023 Tulane report found that in the 2017-18 enrollment matching process, Black applicants were 9% less likely to get a seat in their first-choice school than white applicants seeking the same placement.

Low-income applicants were 6% less likely to get their top choice. Black applicants were particularly disadvantaged in securing a desirable kindergarten seat because they were less likely to meet the qualifications for geographic or sibling preference.

In 2019, the district enacted a policy granting a lottery preference to applicants living within a half-mile of a school, in effect putting enrollment at the highest-performing schools further out of reach for many. In the 2019-20 enrollment cycle, 65% of applicants who lived within these catchment areas were admitted to high-demand schools, versus 28% for all applicants.

4. From 60th to 6th

In 2005, New Orleans schools ranked 60th among Louisiana’s 68 districts in terms of college entry rates. By 2023, it had surged to sixth. As academic outcomes grew, so did graduates’ college readiness — and their ability to take advantage of an unusually strong state scholarship program for those who choose to attend a Louisiana college or university.

But school leaders quickly learned that winning admission to college often does not mean a student will actually show up on campus — much less graduate —in an unfamiliar environment sometimes far from home.

As one of the city’s most successful charter school networks, Collegiate Academies has been repeatedly tapped by the school system’s supporters to develop strategies for addressing gaps in meeting students’ needs. Collegiate’s teachers have been remarkably successful in rolling up their sleeves and solving problems as they come up.

Early college persistence rates were terrible, however. Collegiate’s first school, Sci Academy, opened its doors to a founding class of ninth graders in 2008. At graduation, 97% of the class had been accepted to a four-year college or university. But between 2012 and 2018, just 15% of network graduates had earned a degree in six years or less.

New Orleans youth suffer from some of the highest PTSD rates in the country, but few got desperately needed mental health services at college. Alone and miserable, they dropped out in alarming numbers.

Over the years, the network’s educators have figured out how to get students to prep for entrance tests, burnish their application materials — often convening in the evening at coffeehouses — and put together full-ride scholarship packages.

As they looked at internal data, though, Collegiate staff realized alumni were too often enrolling in poor-performing community colleges and other programs where they did not get help making the transition to a four-year institution. The school network established a formal college persistence program and began enrolling alums in groups at the most receptive colleges.

In early 2020, even as COVID was forcing schools to close, Collegiate was one of two charter networks to launch a program now known as Next Level Nola. High school graduates from any school in the city whose admissions scores and other academic credentials weren’t yet high enough to win a place at a competitive college could sign up for a 14th “bridge” year.

In the free program, youth could work on raising their ACT or SAT scores while earning an entry-level career credential to keep their options open. Last year, Next Level Nola participants earned six associate degrees and nine business operations certificates — meaning 88% finished with a credential.

Collegiate’s overall six-year college graduation rate is still low, at 18% — but better than the national rate of 11% for the lowest-income students, according to the school’s analysis of U.S. Census data. More promising, the number of alums who return for a second year at college is 78%.

One huge shift Collegiate has made has been to send alums to “match” schools — colleges that provide more support, prioritize graduation, connect graduates to potential employers and keep the cost of attendance very low.

“It’s absolutely game-changing for college-bound students in New Orleans,” says Rhonda Dale, Collegiate’s chief of staff.

Collegiate alums have been particularly successful at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s Louisiana Educate Program, which provides intensive academic and social coaching. The program is too new to have a six-year graduation rate, but 94% of Collegiate graduates enrolled return for a second year.

More than half have either earned a bachelor’s or are on track to do so. This is in contrast to a statewide public college graduation rate for Black students of 35%.

It’s still not enough, says Dale: “In the last few years, we have realized that more needs to be done to ensure that students [graduate the Louisiana Educate Program] with their ‘first good job.’ So, we have made a real effort to make sure that LEP students have internships in the summer aligned to their major so they have experience and an understanding of what jobs they might want.”

5. Fewer pre-K seats

The creation of the all-charter school system reduced the availability of early childhood education. In 2005, Orleans Parish public elementary schools offered nearly 70 pre-K seats for every 100 kindergartners. Today, there are fewer than 50 per 100.

Charter operators were not required to offer preschool, and state funding subsidized only a small number of seats at each school. To fill a preschool classroom with enough students to justify the cost, a school — in a deeply impoverished system — would need to find families able to pay tuition themselves.

On top of this, the district’s accountability system focuses on performance in grades 3 through 8, so charter school leaders do not have incentive to offer pre-K programs.

With the backing of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and a number of other philanthropic, governmental and civic organizations, the New Orleans Early Education Network has worked to increase the number of pre-K seats.

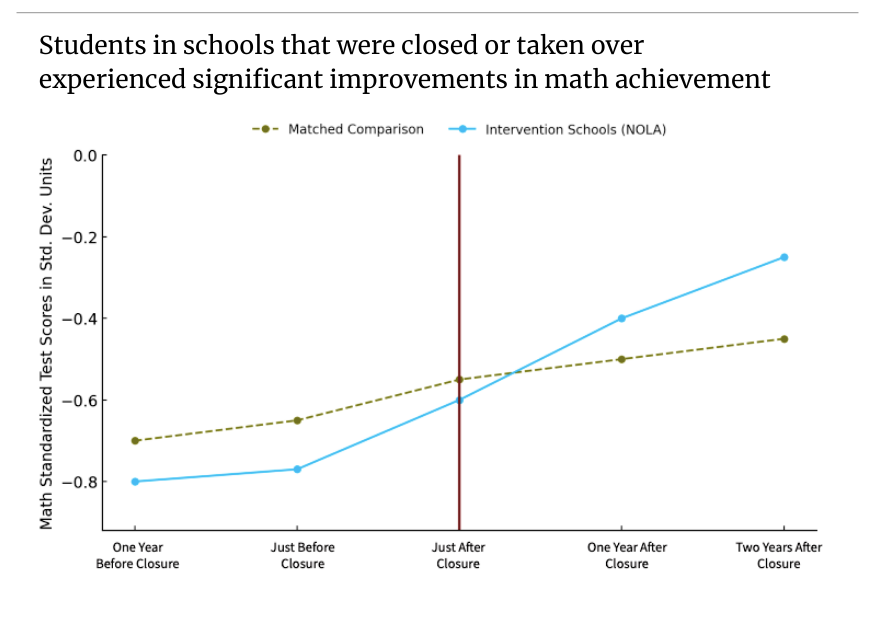

6. Closing underperforming schools drove most of the system’s improvement — but remains deeply unpopular

One of the most important datasets showing the continued academic improvement of New Orleans education landscape is also the most enduringly controversial. Under Act 91, persistent underperformers’ charters are revoked and given to new, high-performing operators.

“This process,” the Tulane researchers tracking the system’s progress declare definitively, “has driven all of the post-Katrina improvement.”

In large part, this is because, unlike in other districts, state laws and local policies are supposed to ensure students end up in higher-performing classrooms than the ones they’re forced to leave.

Yet closing a school — even one that has left successive generations ill-equipped to break out of poverty — is supremely unpopular. Nowhere is this more true than in Orleans Parish, where school communities are closely tied to the city’s history, their legacies celebrated at every opportunity by alumni networks.

The return of the schools to a local board was supposed to bring this decision-making closer to the people most impacted. To literally provide a place where families can go to be heard by their elected representatives.

In practice, even when a school’s flagging performance has been discussed in public meetings for several consecutive years, there is community outcry when the superintendent recommends a closure to the board. Families often do not understand how far behind their children may be academically, or how precarious their school’s financial status is.

Families disrupted by closures are supposed to have priority in the universal enrollment system for seats in better schools. And a nonprofit called EdNavigator is available to help parents understand their options and troubleshoot everything from a child’s need for a particular type of support to transportation.

But closures continue to be dogged by poor communication from the district. In the 2023-24 school year, then-Superintendent Avis Williams seesawed on the fate of F-rated Lafayette Academy Charter School. Typically, its charter would have been given to a higher-performing network, along with its historic and freshly renovated building.

After a series of miscommunications and reversed decisions, Williams acceded to pressure from a board member who had repeatedly decried the all-charter system as “a failed experiment” and announced the district would open and run a traditional program, the Leah Chase School.

Despite questions from the city’s school leaders and others, district leaders did not say whether the new, non-charter school would be held accountable for student outcomes — much less whether other persistently underperforming charter schools would be able to evade closure by appealing to become a traditional school.

As Louisiana’s superintendent of education from 2012 to 2020, John White was one of the architects of the autonomy-for-accountability bargain that is at the heart of the school system’s novel structure. A willingness to engage in tough conversations, he says, “is in the DNA of the system.”

“Acknowledging areas of struggle is part of the deal,” he says.

But so, too, is recognizing what’s possible when a community is willing to engage in tough conversations.

“New Orleans’s education system has been on a protracted march toward achieving a basic civil right, which is the guarantee that, given reasonable effort, all children will learn to read, write, do math and make friends in the schools of our city,” says White. “By most measures, New Orleans is doing better at that today than it was 20 years ago. New Orleans will be a lot closer to that promise in 20 years.”

Graphics by Meghan Gallagher/The 74

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter