Trump Education Plan Raises Fears Over Future of Testing and Accountability

Without a strong ‘federal backstop,’ some experts argue it will be harder to keep states honest and protect the neediest students.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

At a recent virtual discussion on the future of state testing, Maryland education chief Carey Wright drew a line in the sand.

“Even if the feds decide that they’re not going to require statewide assessments, that is not something that I’m going to buy into,” she said. “The moment you lower standards, you do kids a disservice.”

With President Donald Trump on a path to eliminate the U.S. Department of Education and revert power back to the states, Wright’s words gave urgency to a burning issue state leaders have been wrestling with for months.

While Education Secretary Linda McMahon has declared it’s “absolutely” necessary to continue the National Assessment of Educational Progress — which allows the public to compare student performance across states — she’s so far been silent on federal requirements for state testing and the need to identify low-performing schools for extra support. The lack of a plan has left some wondering if sending education “back to the states,” as Trump is fond of saying, means abandoning what has been a mainstay of education policy for more than 20 years.

“This is one of the discussions that the department, the administration, the Senate and House need to talk through,” said Jim Blew, co-founder of the Defense of Freedom Institute, a right leaning think tank that supports Trump’s agenda.

A department official during the president’s first term, he argues that the Every Student Succeeds Act, the law that spells out federal requirements for testing and accountability, has had little impact on holding students to high standards.

“States that do not want to be transparent about their testing results simply aren’t,” he said. “If you don’t believe me, just go and try and find the results for any state.”

As the president’s plan takes shape, some Republicans are trying to remove those annual testing and accountability requirements altogether. Sen. Mike Rounds of South Dakota reintroduced a bill last week that would not only eliminate the education department, but also repeal ESSA. In exchange for a federal block grant, states would be required to submit student data to the Treasury Department, complete an annual audit and follow civil rights laws — but not conduct annual tests.

The rationale is clear, said Charles Barone, senior director of the Center for Innovation at the National Parents Union: Maintaining some federal authority over testing and accountability could imply there’s still a role for the department.

“Sen. Rounds’ bill simply has federal programs as money streams,” he said. “No policy attached.”

Since the pandemic, a handful of states, like Oklahoma, Wisconsin and New York, have rolled back expectations for passing state tests. The changes are likely to result in more students reaching grade-level targets even if they haven’t learned more. The trend has revived debate over the “honesty gap” — the discrepancy between NAEP’s higher standard for proficiency and the often lower bar set by states.

Others, like Wright in Maryland and Virginia education Secretary Aimee Guidera are phasing in tougher assessment and accountability systems. To Blew, that shows the federal government should just stay out of the way.

“At the end of the day, states are going to determine this,” he said. “Let’s give them the freedom to do that.”

Passed a decade ago, ESSA requires states to test all students in third through eighth grades in reading and math, to assess students once in high school and to ensure at least 95% of students participate in testing. States also have to break down results by race and for different student groups, including those in poverty, English learners and students with disabilities.

The major components meet the threshold of what Barone describes as the “bare minimum” for accountability.

Testing every student allows parents to get assessment results for their own children, which can then be used to determine where students are struggling or if they need more challenging work.

Disaggregating the results shines a light on how districts serve historically marginalized students — data that is especially important to policymakers and advocacy groups. Finally, a common test allows for apples-to-apples comparisons across schools and districts.

“Over the years, a consensus has formed that you want certain guardrails in place,” Barone said.

‘A federal backstop’

Observers don’t expect Rounds’ bill to get very far. But some call it a harbinger of a return to the days before No Child Left Behind, the strict accountability law that preceded ESSA. In the 1990s, just a fraction of states tested students every year and many imposed no consequences for failing schools.

“I think accountability is already at a pretty low point,” said Cory Koedel, an economics and public policy professor at the University of Missouri. “If things go back to the states even more formally, I would just expect that unwinding to complete itself.”

Republican Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, who chairs the education committee, is expected to introduce another proposal to eliminate the education department and revamp the role of the federal government in education. Blew said that bill could be weeks away.

Democrats and some state leaders warn that dumping federal testing and accountability requirements and issuing block grants would allow states to turn their backs on the neediest students.

“If you get rid of accountability, you’re just essentially giving [states] a blank check,” said Stephanie Lalle, communications director for the Democrats on the House education committee. Federal mandates, she said, are how you push them to “not discriminate and incentivize them to close the achievement gap.”

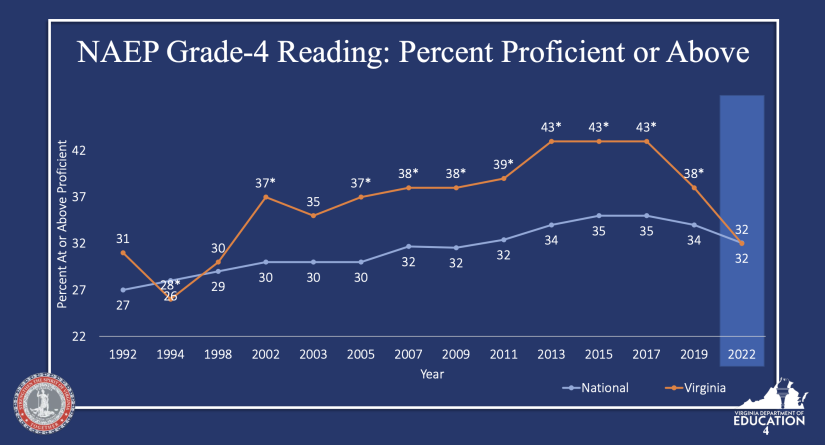

At a February conference on assessment and accountability in Dallas, Virginia ed secretary Guidera shared data showing how her state’s performance on NAEP steadily improved between 2003 and 2013 — the NCLB years.

The landmark education law, which set strict testing and accountability requirements in exchange for Title I funds, passed in 2002. Data shows the policy led to math and reading gains nationally, but it quickly became highly unpopular. The law set ambitious goals for all students to be proficient in reading and math by 2014, but drew considerable pushback from critics who said it led schools to teach to the test. But even if states continue their own testing and accountability systems, Guidera doesn’t want Washington out of the picture.

“We need the federal backstop,” she told The 74. “We have to have high standards, and we need to be honest with ourselves about where every child is.”

‘A rallying cry’

Opposition to standardized testing comes from both the left and the right. Educators grumble that it eats up too much class time and that results from spring tests come back too late to help students or make adjustments for the fall. Others, especially teachers unions, say state tests offer a narrow view of student learning.

The question is what states would do if the federal government were no longer in the picture. In his conversation with Wright and other experts earlier this month, Scott Marion, executive director of the Center for Assessment, leaned on a handy metaphor: a motorcycle cop holding a radar gun.

“What if nobody was checking your speed?” he asked.

State leaders have been thinking about the possibilities.

Rep. Robert Behning, an Indiana state legislator, said he “would be willing to look at other options, like sampling” — giving tests to a random, representative group of students instead of everyone. That approach can be less of a drain on teachers’ and students’ time and still give the public district and school-level results. But the tradeoff is that most parents would be left in the dark about their children’s performance.

Other state leaders like the idea of spreading assessments throughout the year rather than building up toward one big test.

“We’ve got better assessments that tell us more about our students,” Eric Mackey, Alabama state superintendent, said during a different webinar in March.

But research shows there are challenges with arriving at a final score for the year and the model might not reduce testing time.

Marion suggests giving state exams every other year, which would allow more time in the intervening years to employ innovative methods like asking students to complete a project to demonstrate their learning.

Marianne Perie, an assessment expert who advises states on test design, said she wouldn’t be surprised if Oklahoma completely stopped giving statewide assessments. In March, state Superintendent Ryan Walters questioned the integrity of the 2024 results, even though they were included in annual report cards for districts and schools.

But in other states like Tennessee and Mississippi, annual tests have been “a rallying cry” for parents and policymakers, said Emily Oster, a Brown University economist who tracks states’ pre- and post-COVID performance.

Such states “have championed their gains in the last few years,” especially in English language arts, she said.

Tennessee, for example, was among the first to bounce back from pandemic-era learning loss. At the same time, the fact that roughly 60% of third graders still scored below grade level in reading was worrisome enough to lawmakers that they passed a law requiring students to be retained or get extra help over the summer and retake the test.

Remote learning during the pandemic and in-depth reporting on poor literacy instruction has also motivated more parents to push for improvements.

“Parents are increasingly demanding accountability from their educational system, which will make sunsetting these assessments more complex,” Oster said.

Roughly 80% of parents value state assessments and think they should be used to guide support for struggling schools and students, according to a National Parents Union poll.

‘Come up with something better’

If the federal government does hand more control over assessment and accountability to states, Barone said it’s far more likely to happen through waivers from McMahon than legislation.

ESSA allows the secretary to excuse states from annual assessments. That’s what former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos did in 2020 during the pandemic. She waived the accountability provisions for both 2020 and 2021. Barone sees no reason why McMahon wouldn’t do the same.

A former Democratic staffer in the House, he thinks it would be hard to improve on the existing testing regimen. But even he agrees that the accountability side of the equation hasn’t led to measurable progress in how states support — and attempt to turn around — their most troubled schools.

The law requires states to identify the lowest-performing 5% of schools, analyze why they’re struggling and adopt a proven strategy for improvement, like coaching teachers or changing leadership. But a 2024 Government Accountability Office report found that less than half of states were complying with those requirements.

“There’s not a lot of evidence that even those that are doing it are doing it well,” Barone said. Maybe Trump’s planned overhaul of the federal role in education, he said, is an opportunity to “come up with something better.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)