Skyrocketing Test Gains in Oklahoma Are Largely Fiction, Experts Say

Frustrated local officials say state chief Ryan Walters has failed to explain how the state lowered proficiency targets.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated August 23

Oklahoma school districts got some shocking, but welcome news this month when the state released results of student tests from last school year.

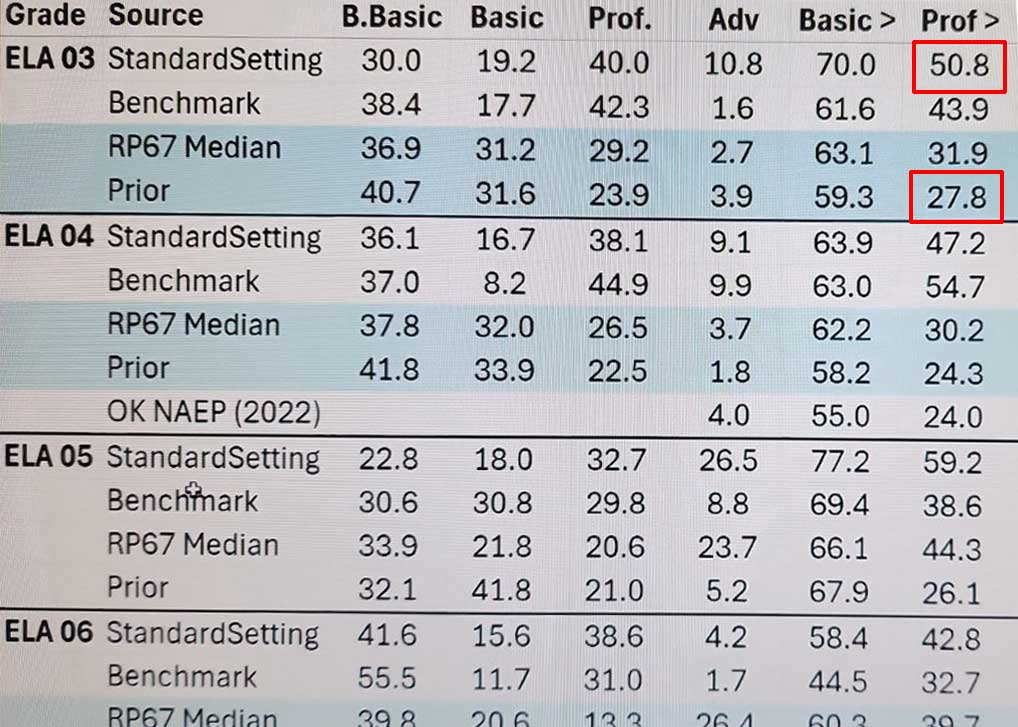

Student performance, especially in English language arts, appeared to have skyrocketed. A highlight: An impressive 51% of third graders scored proficient or better, compared to 29% last year. The reported jump came a full eight years before the majority of Oklahoma students are expected to reach proficiency under the state’s plan to meet federal accountability laws.

But elation quickly turned to disbelief as local officials took a closer look at the data.

“Nobody makes jumps of that size,” said an assessment director from a school system near Oklahoma City. The official asked not to be named because she does not want to “put a target” on her district.

To put the outsized gains in perspective, The 74 asked Andrew Ho, a leading testing expert at Harvard University, to review the results.

Math progress in Oklahoma, where student performance has long trailed the national average, was two to 10 times that of states with the strongest growth, depending on grade level, he said. In reading, gains were 10 to 20 times greater.

“If this is true, … the average fourth grader will be reading and writing like last year’s average sixth grader,” said Ho, a former member of the National Assessment Governing Board, which sets policy for the federal test widely known as “the nation’s report card.”

As Ho surmised, Oklahoma’s purported gains are largely illusory.

Interviews with those familiar with the state’s testing process, as well as emails and other documents shared with The 74, reveal that the scores don’t reflect true growth, but a decision by the state, under the auspices of Superintendent Ryan Walters, to lower the bar for proficiency.

“Last year, you needed to know more to get proficient,” said a source familiar with the work of a Technical Advisory Committee the state convened this summer to examine proficiency targets. But the source, who asked not to be named because of ongoing work with the state, said “this year, using the same items, you didn’t need to know as much and you’re still considered proficient.”

It is not uncommon for states to massage results of large-scale assessments, particularly after they institute new standards. This past spring was the first time Oklahoma students took tests reflecting a 2021 update to language arts standards and 2022 math overhaul. But states often accompany such complex shifts with attempts to communicate, first to districts, and then to parents, how they were made and what they mean.

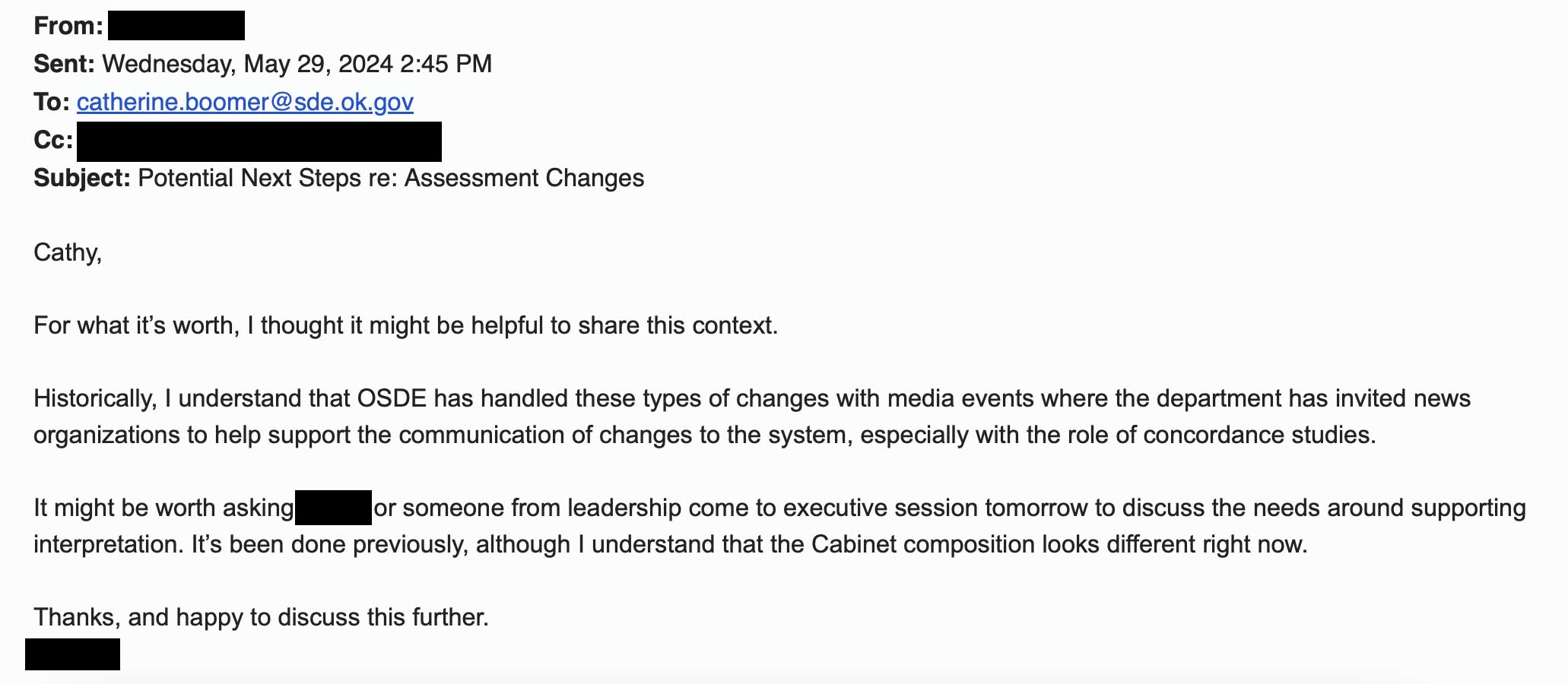

“Historically, I understand that [the department] has handled these types of changes with media events where the department has invited news organizations to help support the communication of changes to the system,” a member of the Technical Advisory Committee wrote in May to Catherine Boomer, the department’s assessment director, according to an email shared with The 74.

Boomer referred questions to the department. As of Wednesday evening, a spokesman for the department had not responded to calls or emails from The 74.

In a press conference following Thursday’s monthly state Board of Education meeting, Walters denied the results had been released, despite the fact that the state posted scores on its website Aug. 1. He called media reports “gaslighting” and “fan fiction.” He said his office had yet to make a “big announcement” about the new scores because staff was still working with districts to “make sure the context is there.”

But districts say the state has offered no communication about how to interpret the results. A statement from the Tulsa Public Schools, the state’s largest school district, said the department has not yet issued guidance on how to compare the data to previous years, a “technical guide” on the scoring changes or any indication of how the results will affect low-performing schools.

An email dated Aug. 14 showed the department was moving in that direction. Julie DiBona, the vice president of program management at Cognia, the state’s testing vendor, told the technical panel that education department officials were asking for a meeting to discuss scores. On the agenda: “How to lead public discourse around comparing the results of the new tests with the old tests. “

A spokesman at Cognia declined to comment.

But that meeting hasn’t happened. In fact, Walters recently praised early results in Tulsa but made no mention of the internal machinations over scoring. The district demonstrated a remarkable 16 percentage point increase in students scoring proficient or advanced in grades 3 through 5.

“The numbers are tremendous,” Walters said at a state Board of Education meeting last month.

The disconnect has left many local officials at a loss.

“I am not alone in believing that the gains demonstrated on [the state test] would be nearly, if not completely, statistically impossible” in a normal year, Stacey Woolley, the Tulsa district’s board president, told The 74.

In the Moore Public Schools, for example, almost two-thirds of third graders scored proficient or advanced in reading, compared to 38% last year. In Stillwater, about an hour north, the percentage of fourth graders in those top tiers jumped 21 points.

Some put the blame for the communication breakdown on Walters, who has spent the summer mired in messy political brawls and controversial academic initiatives. In June, Walters drew national scrutiny by requiring all public schools to teach the Bible. Last week, citing a lack of transparency and failure to distribute funds to districts, at least two dozen Republicans said they’d be seeking an impeachment investigation against him. And on Tuesday, a federal audit by the U.S. Department of Education said his department needs to improve financial management, and called it out of compliance in areas such as testing and handling Title I funds. Walters blamed the previous administration for some of the concerns.

“There are red flags all over the place,” said Erika Wright, leader of the Oklahoma Rural Schools Coalition, who called the lack of communication from the state part of the superintendent’s “dismal track record on honesty and transparency.”

‘Moving the goalpost’

Parents rely on testing data to understand what their children are learning, and the resulting proficiency rates help establish school grades in the state accountability system. Officials use those figures to determine which students and schools get extra academic support.

That’s one reason why calibrations like the one in Oklahoma are common.

In May, Clare Halloran, a researcher at Brown University, confirmed the updates to the state’s standards with Alyssa Tyra, who oversees English language arts at the Oklahoma education department. Halloran works on a project tracking state assessment data.

“They confirmed that 2024 is a new baseline and not comparable to prior years,” Halloran said. When states change standards, “a lot of times you’ll either see a big drop or a larger increase than normal. It’s essentially because they’re moving the goalpost a little.”

Teachers analyzed test items and recommended how much content students needed to learn to place in each of the four performance ranges, from below basic to advanced. On a 200-400 scale, 300 is the cut point for proficiency. Emails show the advisory committee was uneasy about leaving the scale as is, but the state decided not only to keep 300 as the proficiency cut off but that students didn’t need to get as many correct items to reach that level.

The official with the Oklahoma City-area district said the data has left her wondering how much progress students actually made.

“It would have been nice to celebrate that we made gains, instead of just feeling that this is not accurate,” she said. “It’s not representative of the hard work we’ve been doing.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)