Why Learning Loss Is Prompting Educators to Rethink the Traditional School Calendar: Start Earlier, End Later, Extend Breaks for Remediation

By Jo Napolitano | January 18, 2022

Pandemic-related school closures, which caused an alarming rate of learning loss among the country’s most vulnerable students, have prompted some administrators to reconsider the school calendar.

An earlier start date, a later end date and numerous, elongated breaks throughout the year could allow more timely remediation for children in need — and enrichment for those who are not.

New York City’s new schools chancellor David Banks, has proposed that children in the nation’s largest district report to class on Saturday and during the summer. In neighboring Connecticut, Hartford Public Schools have already started opening several buildings on Saturdays, offering some 800 students who have fallen behind a chance to accelerate their learning.

Such thinking has received at least tacit support from U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona. “Why do we go back to the same system that gives kids two months without engagement in the summer?” he asked in November. “We need to rethink that.”

The suggestion comes as the fast-spreading Omicron variant is again forcing schools to struggle to remain open. Even before the latest surge hit, districts had begun scaling back — moving to four days of instruction per week and adding days off to their calendars — in an effort to curb teacher burnout.

While any change to the school calendar typically involves negotiation — and possibly opposition — from the teachers union, Banks said he’d gladly employ members of the community if New York City’s United Federation of Teachers pushes back.

“People think that means 300-plus school days. That is not the case.”

—David G. Hornak, National Association for Year-Round Education executive director

Schools throughout the rest of the country are considering their options: An influx of federal dollars meant to address long-standing achievement and opportunity gaps could bring about real change. Meanwhile, a less-rigid calendar might lead to greater flexibility for COVID-related emergencies, allowing districts to more easily consider closing for a week or two to quell an outbreak, knowing they could make up the time later.

Harris M. Cooper, Hugo L. Blomquist Distinguished Professor Emeritus of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, said it’s too early to make predictions about whether more schools will switch to balanced or modified calendars. But the chaos of the last two years might make it more attractive to families that have already weathered major shifts in scheduling, he said.

“They’ll say, ‘Hey, the kids were home in the wintertime and it wasn’t necessarily a bad thing,’” Cooper said.

Still, a fundamental shakeup to the traditional calendar might be a tough sell. David G. Hornak, superintendent of Holt Public Schools in Michigan and executive director of the National Association for Year-Round Education, said many who are new to the concept are left with the wrong impression.

“People think that means 300-plus school days,” he said. “That is not the case.”

Instead, most districts that implement the program still operate on a 180-day schedule. The additional or elongated breaks, called “intersessions,” are optional: Districts can’t mandate that children return to the classroom — nor can they demand teachers lead these lessons. All are invited to participate, but some will no doubt choose to stay home.

Washington state is so taken by the prospect of curbing learning loss by modifying the school calendar that it’s offering grants of up to $75,000 to districts to examine its feasibility. So far, 22 have been awarded pilot funding, using the money to spread the word in their community, organize stakeholder groups, conduct surveys and visit campuses that already have the plan in place.

“COVID gave us a chance to think outside the box, to look for different ways to reach students, moving away from the cookie-cutter approach,” said Jon Ram Mishra, assistant superintendent of elementary education, early learning, special programs and federal accountability for the Washington state education department.

A former special education teacher, Mishra believes all children would benefit from the type of individualized learning plans he once crafted for his own students. A balanced calendar, one with built-in flexibility in how it rolls out the typical 180 days of instruction, allows kids an opportunity to spend more time in the classroom if needed, offering them a more tailored experience than the traditional model, he said.

Kevin Chase, superintendent of Educational Service District 105 in Washington’s Yakima County, which serves some 66,000 children, points to yet another benefit: He said the plan allows schools to provide remediation closer to the time when a student first struggles, rather than months later during a summer session.

“This is my 30th year in education,” he said. “I know the need for intervention is for it to be timely.”

And, Chase said, longer breaks throughout the year — many participating districts shave six or seven weeks off of the typical 12- to 13-week summer vacation — help teachers recharge. They also allow families to spend more time together during the holidays, with, oftentimes, a full week off for Thanksgiving.

Hornak estimates 4 percent of the nation’s roughly 50 million public schoolchildren attend so-called “balanced calendar” schools. Several campuses within the Dallas system operate under this model, as do those in Hopewell, Virginia and Camden, South Carolina. Other schools around the nation are considering the idea, including those in Lee County, Florida, Richmond, Virginia and Cincinnati, Ohio.

Hornak said the approach has many merits, including that it cuts down on the amount of time teachers spend reteaching the previous year’s curriculum, which, using a traditional calendar, could take up to 40 days.

The cost of remediation in grades K-12 can bleed into a student’s future: Those who graduate unprepared for college pay out of pocket for remedial courses covering topics they should have already mastered.

The balanced calendar is particularly helpful for economically disadvantaged students who suffer mightily during the summer with few opportunities to learn, Hornak said. It also allows those educators who choose to participate a chance to make additional cash — and student teachers to sharpen their skills.

But not everyone seems eager to make the switch: 66 percent of 1,500 parents surveyed nationwide in November said they did not support a longer school year. Seventy-three percent opposed longer school days and 67 percent spoke out against a shorter summer vacation. San Diego, which had 134 traditional and 39 year-round schools, paid millions in recent years to transition its year-round campuses to a traditional calendar, citing, among other factors, scheduling conflicts for families with children in different schools with differing breaks.

“My sense of both our data and other people’s data is that parents pretty much just want things to be normal,” said Morgan Polikoff, associate professor of education at the University of Southern California, who co-directed the study. “They felt like the school calendar worked for them and their kids.”

Polikoff attributed parents’ attitude to a lack of understanding and awareness about learning loss: Many schools lowered standards and suspended letter grades and testing during the shutdowns, so they didn’t see evidence that their children had fallen behind. A full 84 percent of parents in that same survey said they were not at all concerned or only a little concerned about the amount of time their child spent learning.

“If that is the case, why would they support a radical change in the school calendar?” he asked.

Still, he said, he believes extending the time a child spends learning is greatly beneficial, especially after a year of staggering loss. According to one study, students in majority-Black schools are now a full year behind those in mostly white schools, widening an already persistent achievement gap by a third, according to a new analysis by McKinsey & Co.

“The more time kids are in class, the better,” Polikoff said, adding that schools that have a truncated school week also tend to see losses in terms of student achievement.

“Teachers said the intersession provided a break for people who needed it. Others worked the intersession and felt a passion again for teaching.”

—Mark Anderson, Highland School District 203 schools superintendent

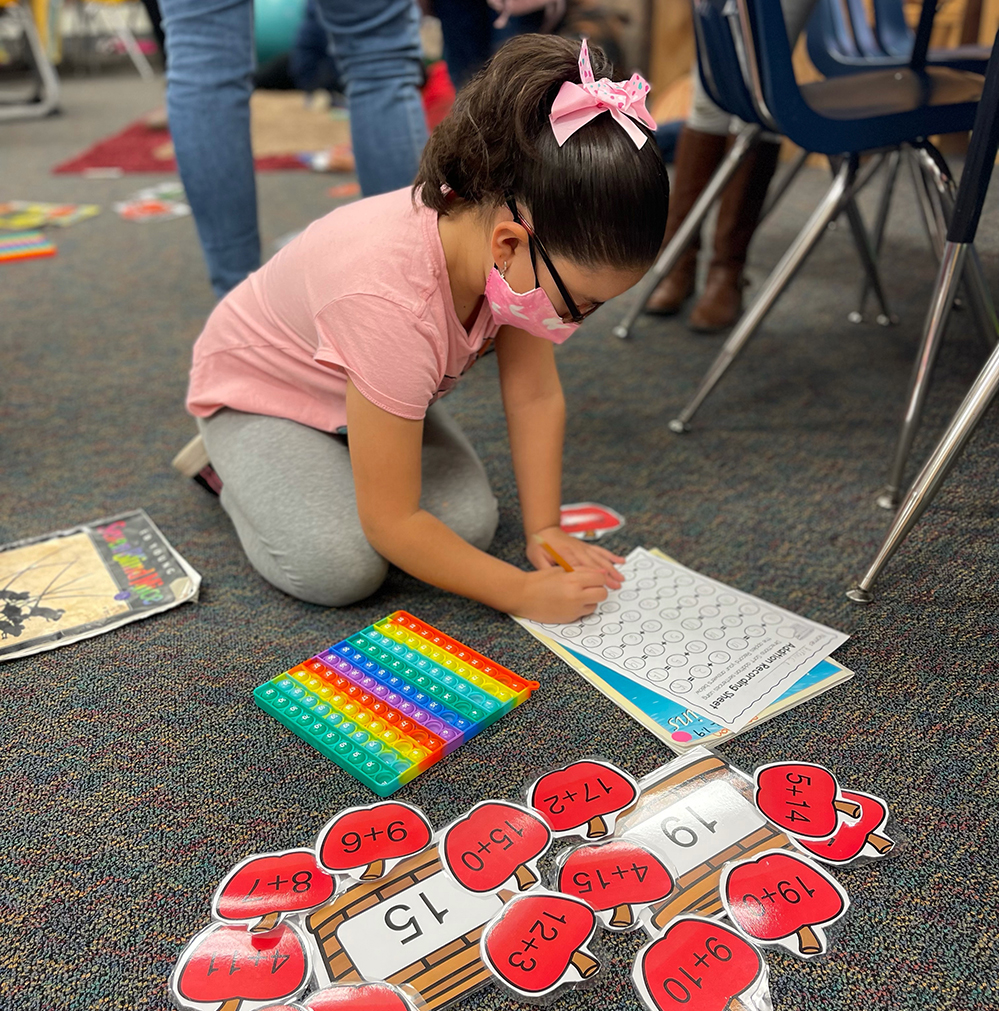

Highland School District 203 in Cowiche, Washington, roughly 150 miles southeast of Seattle, implemented a modified calendar for the first time this school year. More than 50 percent of its 1,200 students participated in the Oct. 25-29 intersession with kindergarteners building catapults to launch mini-pumpkins, first and second graders constructing weight-bearing bridges and high schoolers working on coding and robotics.

School Superintendent Mark Anderson said the program is off to a strong start: It scored high among participants in a recent survey earning a 4.5 out of 5.

“Teachers said the intersession provided a break for people who needed it,” he said. “Others worked the intersession and felt a passion again for teaching.”

But the cost — approximately $300,000 per year — remains a concern in a district with a roughly $20 million annual budget. The superintendent hopes the state will continue to fund the plan long after COVID dollars dry up.

“We would hate to see that this is a success and we can’t continue it,” he said.

Vanessa Williams, a high school English teacher who has been with the district for 27 years, said she feels less burned out now as compared to this same time period in years past — even though she taught during intersession.

She said the current model is better for children — it gives them a sense of control after nearly two years of disruption — and teachers. And she doesn’t speak only for herself: She’s head of the teachers union.

“Since intersession did not add days to the teachers beyond what was contracted, and because it allowed teachers to make extra money … the union was on board,” she said, adding, “it helps that they had a say in what the balanced calendar was going to look like.”

Melissa Benicio Jimenez said her 6-year-old took part in the October session and relished the opportunity to learn in a more creative and relaxed setting. Her high school-aged children were not as enthusiastic.

“I chose to stay home because I still wasn’t adjusted to the new schedule and I didn’t like it at the time,” said 15-year-old Andrew.

But, he said, he’ll likely attend the January intersession because it will give him a chance to visit area colleges in preparation for a possible career in law enforcement.

“Now that I’m used to it and I see how it helps,” he said, “I kind of like it.”

Lead Image: Elementary students at Highland School District 203 in Cowiche, Washington, work on STEM-related projects during an October break in which children were invited to class to continue their education. (Mindy Schultz)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter