What’s in a Report Card? Depends on Who You Ask. New Report Shows That Parents and Teachers Have Very Different Understandings of Grades & Tests

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

If a child earns a B– in math on his report card, is that a good grade, or does it mean he’s the worst in the class?

Ask a parent and a teacher, and you’ll likely hear very different answers. But that disconnect is just the beginning when it comes to how these two groups understand the education system and all the grades, jargon, and communication within it, according to a new report from the nonprofit Learning Heroes.

“We’re not helping parents in ways that we should be to make sure they have that complete, accurate picture of how their child is achieving,” said Bibb Hubbard, founder and president of Learning Heroes. “The system puts all these barriers in the way.”

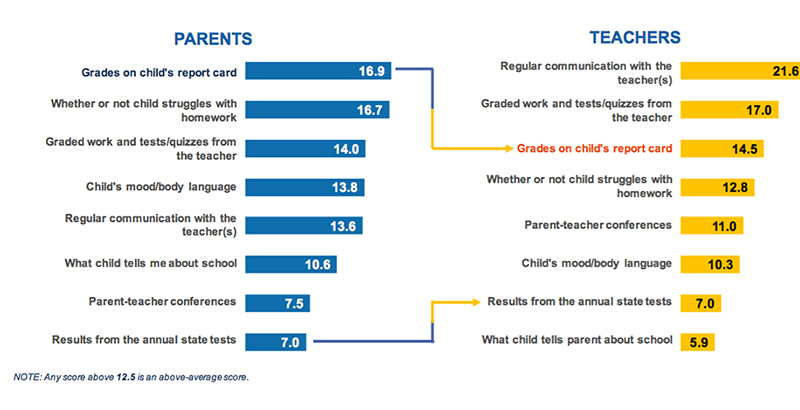

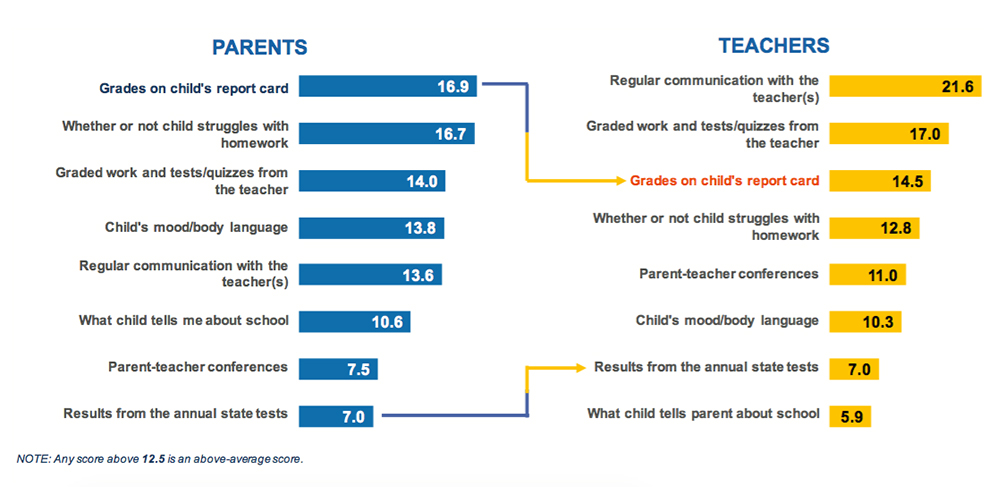

One of those barriers, Hubbard said, is the report card. It’s the No. 1 way parents say they know how well their children are doing academically. But report cards usually fail to say whether students are performing at grade level. The survey found that most parents — 6 in 10 — said their children earn As and Bs, which they think means their kids are performing at the level they should be for their grade.

But teachers said report cards are only the third-most important tool for understanding student achievement. For teachers, a report card is a combination of grades, effort, and progress. About one-third of teachers said they feel pressure from administrators or parents to avoid giving too many low grades, and more than half said they are expected to let students redo work for additional credit.

“I think grades have been inflated for years — 100 percent,” an elementary school teacher from New Hampshire told Learning Heroes. “I think most teachers would be lying if they didn’t say a B–, C+, C are the lowest kids.”

This disconnect was surprising, Hubbard said.

“To hear teachers qualitatively say, ‘Oh yeah, report cards do not measure achievement alone and do not equate to grade level,’ and then to hear the juxtaposition of parents who … say, ‘That’s what I have to go on — that’s all I have to know if my child is achieving,’ was just really powerful,” Hubbard said.

Parents usually receive their child’s state test scores from the previous school year in the summer or fall. While these scores show whether or not students were on grade level, they can sometimes be difficult to decipher, Hubbard said, and parents often see them as old news.

“Parents say, ‘My child is wearing a different shoe size, they’ve grown 3 inches since they took that last test, of course they’re not in the same place that they were last year,’ so when the results come in, if they come in such a delayed time frame, they feel less relevant for parents,” Hubbard said.

There’s a big gap between how well parents think their children are doing and how well students across the nation actually perform. While about 90 percent of parents surveyed in 2017 said their child was achieving at or above grade level, only 30 to 40 percent actually were, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which looked at fourth- and eighth-graders’ performance in math and reading.

The Learning Heroes survey found that teachers feel untrained and unsupported in how to have difficult conversations with parents. Teachers said that when they tell parents about their child’s poor grades, some parents blame the teachers and some don’t believe them. A little more than half of teachers said they have no training on how to talk to parents about their child’s academic challenges.

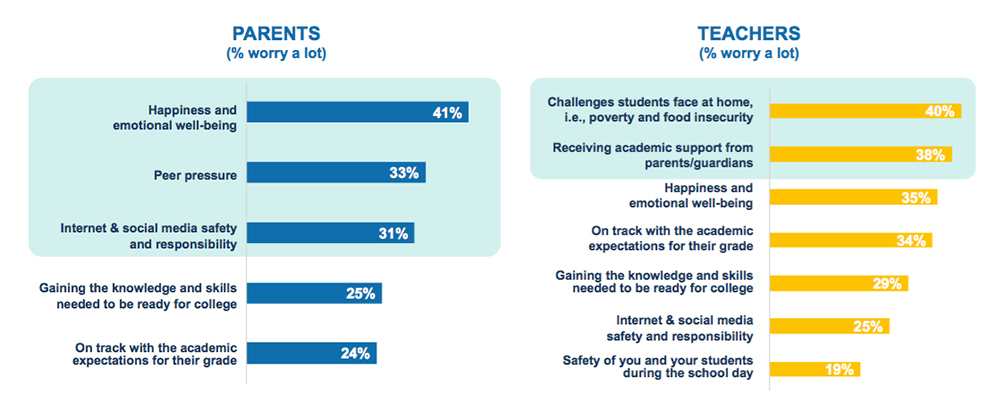

Another area of disconnect is which worries parents and teachers have about their students. Parents are most concerned about the happiness and emotional well-being of their children, while teachers are most worried about challenges students might face at home, like poverty and food insecurity. Teachers are more worried about a student being on track academically than parents are, with about one-third of educators citing this as a worry, compared with one-fourth of parents.

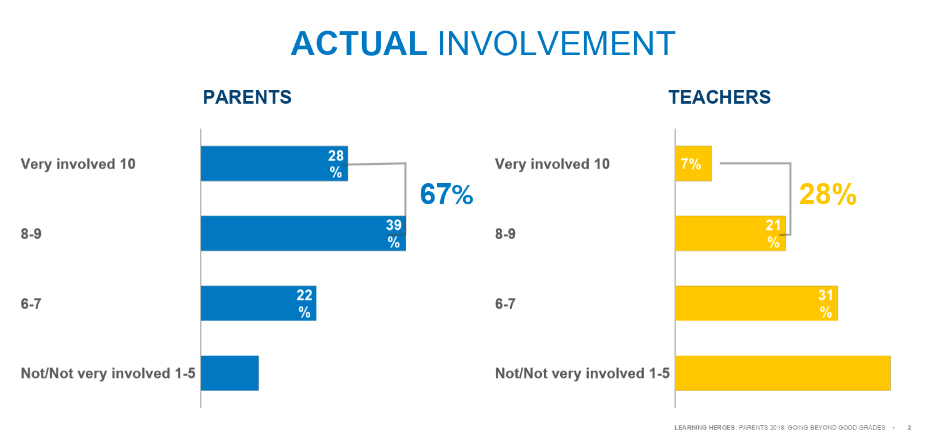

There’s also a gap between how much parents think they’re involved in school versus how much teachers say they are. While two-thirds of parents said they rank their involvement in school between 8 and 10 on a 10-point scale, only 28 percent of teachers said they consider it that high.

“Parents definitely believe that they are doing a good job being involved, without a doubt,” said Adam Burns, chief operations officer of Edge Research, which conducted the study. “What’s really fascinating is that teachers see it very differently.”

To get parents and teachers on the same page, Learning Heroes recommends that schools provide more information about whether students are performing on grade level, like using a worksheet its team developed that provides this information and advice for how parents can help students at home. To improve communication with parents, Hubbard recommends using established programs like home visits or “Academic Parent Teacher Teams,” a model that allows more time for teachers to meet and collaborate with parents.

The report includes both qualitative and quantitative data collected by Edge Research in 2018. The study consisted of two nationally representative online surveys of both parents and teachers, as well as focus groups of parents, teachers, and students.

Disclosure: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York provide funding to Learning Heroes and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)