‘We’re Doing School in a Different Way’: One Nonprofit Took Early Lead in Preparing Districts for Distance Learning During Pandemic

When she read in late February that the coronavirus could infect as many as 70 percent of Americans, Emily Freitag was “primed” to prepare for its effect on schools. She grew up near New Rochelle, New York, one of the first U.S. hot spots of the virus, and her husband, who analyzes international hotel data, saw the effects of the looming pandemic early.

Freitag is a cofounder and CEO of Instruction Partners, a nonprofit that works with 106 school systems around the country to ensure “equitable access to great instruction for students in poverty, students of color, students learning English, and students with disabilities.” Under normal circumstances, the organization helps small school systems, where teachers and staff are often stretched thin, deal with what the organization calls “the unglamorous stuff that is often overlooked” — coaching models, curriculum design and professional development.

Back in February, Freitag remembers thinking, “If this [pandemic] actually happens, this is just going to be so seismic for schools.”

Freitag and her team began preparing their response Feb. 27, starting with a blog post with guidance for school leaders bracing for school closures.

“It is time for schools to seriously think about their learning resiliency plans to guarantee that illness closures do not prevent them from fulfilling the mission of advancing student learning,” Freitag wrote.

In the following days, Instruction Partners created a COVID-19 Resource Hub on its website that offers guidance on best practices for transitioning to distance learning and specific resources for schools to use when teaching students. Instruction Partners is updating and adding to the hub as districts experiment with distance learning.

Since then, 47 states have shut down all public schools, leaving more than 55 million students out of class, according to a rolling count by Education Week. For many educators, the first step was to make sure students were safe and had access to food. Meanwhile, Instruction Partners was working to make sure schools would have relevant resources for remote learning available when they were ready to focus on academics. Some districts launched online learning programs right away, while others took a week or longer to make plans.

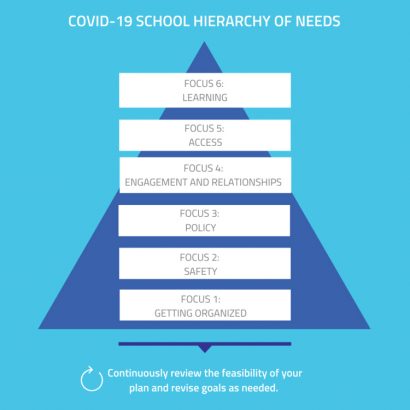

To help districts plot a path forward, the organization created a “school hierarchy of needs” that ranges from getting organized and making a plan for distributing student meals to helping students learn from home and planning for regular school to begin again.

Here are some of Freitag’s tips for educators trying to make distance learning work during the pandemic:

- Make sure every student has a point of contact — a go-to adult who can act as a “virtual homeroom teacher” — and try to keep caseloads for those adults as small as possible.

- Establish a system of daily communication between students and teachers.

- Create weekly routines for teachers, who might be working remotely for the first time

- Send the message “We’re doing school in a different way” rather than “School is closed.”

- If you have devices at school, get them home to students who need them to access online learning.

- Take it one week at a time: Plan for one week, then readjust for the next week.

- Design solutions for the most vulnerable students, such as those in special education, first — and then apply them to all students.

- Project calm and be solutions-oriented. Focus on health, safety, wellness and learning for all students.

Freitag said there are three general ways school systems are doing distance learning: digital, analog and hybrid. The digital model, which is likely most common in high school and in classes where all students already had their own devices, resembles an online course in which students log in to digital classes and receive and submit assignments through an internet learning platform. Some school systems might choose to go analog, relying on hard-copy packets and textbooks, with teachers making regular phone calls to check in on students and collecting all the work when school reopens. Finally, a hybrid model combines the two, perhaps with teachers holding class on a video platform like Zoom or Google Hangouts and students submitting work using a range of tools from Google Docs to text messages.

The hub includes various resources, including templates for meeting notes for educators gathering — virtually or in person — to plan for distance learning, sample student schedules for specific grade levels for each type of distance learning, and a template for educators to use to evaluate online lessons and worksheets. The hub also links to specific ready-to-use resources, such as Curriculum Associates, which offers free printable math and reading worksheets for students in kindergarten through eighth grade.

The support from Instruction Partners proved valuable for Allison Leslie, chief academic officer at Compass Community Schools, a charter network in Memphis, Tennessee. Leslie, whose school system has been an Instruction Partners client since it opened last year, first spoke with Freitag about potential closures March 11 and has used the Resource Hub to guide the network’s response to school closures.

Instruction Partners “really anticipated this in a great way and put together lots of tools and resources that we pulled from the website,” she said. Additionally, Instruction Partners helped network leaders plan professional development sessions about remote teaching and choose which of their existing resources they should use.

Like many educators and leaders, Freitag is worried about learning loss among those who are already vulnerable, particularly students with disabilities. Many parents and educators are still figuring out how to meet these students’ needs, and the issue has become a barrier to distance learning in some places. For example, Philadelphia district officials worried that remote schooling might not be accessible for all students, so they instructed principals not to attempt it at all.

“This is absolutely an urgent and significant threat for lots and lots of kids,” Freitag said. “I also believe educators are capable of doing a lot. And I think everyone is reeling right now, but I think if we take this one step at a time together we will find solutions.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation, and Carnegie Corporation of New York provide financial support to Instruction Partners and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)