States Are Raising the Bar for Their Students, New Report Shows, but Higher Standards Are Not Driving Higher Test Scores

States are setting higher expectations for student academic performance, according to a new report in the journal Education Next. The authors find that proficiency standards on state tests have grown more stringent over the past few years, defying worries that they would be dumbed down as the federal government took a more detached approach to school accountability. But higher standards don’t seem to have yielded higher performance.

The report, written by Education Next editor and Harvard professor Paul Peterson, is the latest installment in the journal’s ongoing effort to track standards over time.

Since 2005, the journal has regularly measured the percentage of students rated as “proficient” — i.e., on track for college — on their respective states’ standardized tests. That proportion is then compared with the percentage rated proficient on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a rigorous test seen as the gold standard among education experts. If states set their proficiency bar high, the difference between their own tests and NAEP should be small.

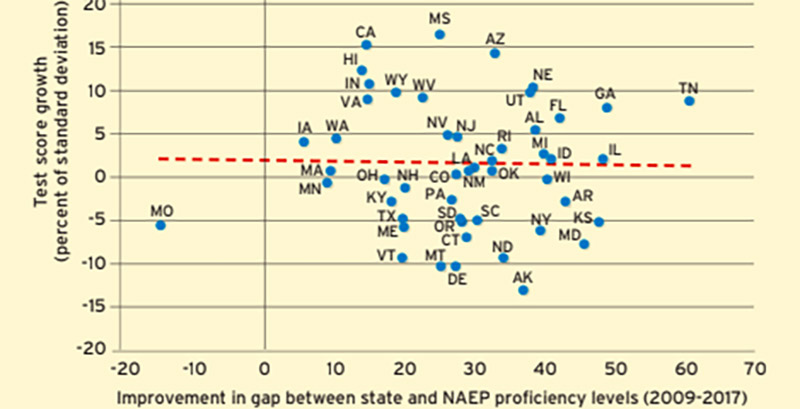

For years, those disparities were instead gaping. In 2009, the difference was 37 percentage points on average. Because so many states set low standards for student performance, millions of parents believed that their own children were well prepared for life after high school, when according to NAEP, they were actually falling behind. The phenomenon was known as the “honesty gap.”

That all changed after 2009, when the Department of Education under President Obama offered financial incentives to states to adopt the Common Core State Standards (or else design local versions derived from them). Over the past decade, as dozens of states have lifted their own proficiency standards, the honesty gap has shrunk by about three-quarters.

But then the Common Core proved politically radioactive as a coalition of teachers unions, anti-testing parents, and conservative activists pushed to eliminate them. After the passage of the federal Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015, which explicitly barred the federal government from incentivizing states to alter their academic standards, some feared that state standards would once again be weakened. After all, with a lower bar comes more students who can vault over it (and more happy news reports about improved performance).

But that hasn’t happened. Even as the federal Department of Education has taken a decidedly lighter touch, states haven’t rushed to reopen the honesty gap.

“The standards could easily have slipped, because the new law doesn’t allow the federal government to do anything to sustain them, and there’s been a lot of political opposition,” Peterson told The 74. “You would have thought some states would have backed away.”

Indeed, some 43 states received a B-minus grade or better from Education Next on their standards, while 16 states and the District of Columbia earned either an A or an A-minus. By comparison, only two states received a grade of B or better just nine years ago.

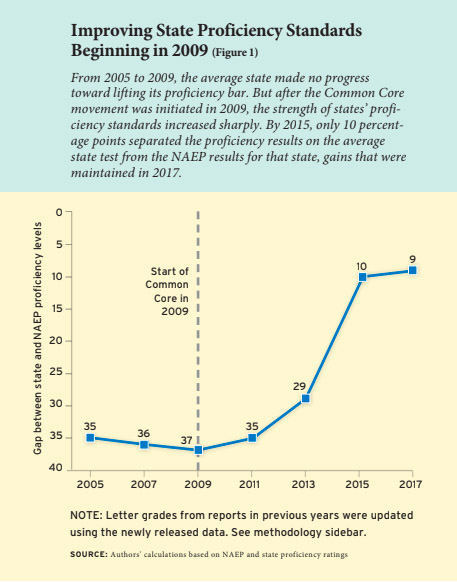

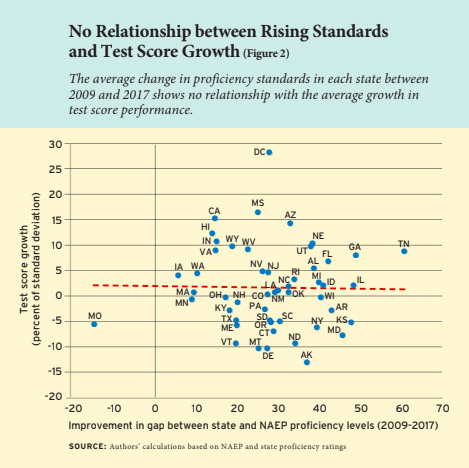

But more rigorous standards have not led to higher performance. Federal NAEP scores for both reading and math have been essentially flat over the past decade, even as states were adopting Common Core and making their own standardized tests more difficult. Just as other school reforms haven’t moved the needle on NAEP results, higher proficiency standards haven’t either.

“We find no correlation at all between a lift in state standards and a rise in student performance, which is the central objective of higher proficiency bars,” Peterson writes in the report. “While higher proficiency standards may still serve to boost academic performance, our evidence suggests that day has not yet arrived.”

A few states, such as Tennessee and Georgia, have seen bumps to their NAEP performance after adopting tougher proficiency requirements. But others, such as Kansas and Maryland, have made similar strides while experiencing no growth — or even a decline — in test scores.

“The first result from the test score information is sort of concerning,” he said. “Because if you don’t see any correlation between a lifting of standards and a lifting of performance, you wonder just how useful those standards are.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)