The 5 Ways DeVos’s Reported New Title IX Rules Would Change Sex Assault Investigations

The Education Department and Republicans in Congress have unwound a host of major Obama-era policies, from protections for transgender students to tough school accountability rules under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

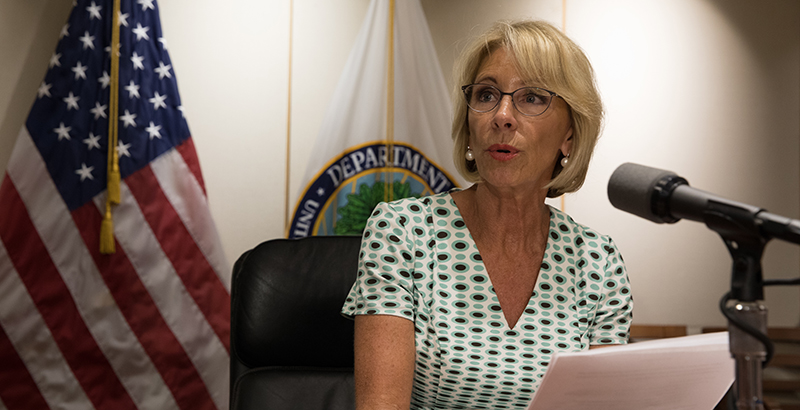

Now, according to The New York Times, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos will make major changes to the way colleges — and K-12 schools — must respond to allegations of sexual assault and harassment under Title IX, which prohibits discrimination in education on the basis of sex.

Critics have long said that the 2011 Obama administration guidance, which was made through a “Dear Colleague” letter, didn’t go through the proper rulemaking channels and, in encouraging schools to beef up investigations and protections for victims, unfairly tipped the scale against the accused. Women’s groups said undoing them would revert to a time when sexual assaults were swept under the rug.

The proposed regulations, which the Times reported late Wednesday afternoon, come almost exactly a year after DeVos first announced, to much criticism from victims and feminist groups, that she would alter the standards and boost protections for alleged perpetrators.

“The truth is that the system established by the prior administration has failed too many students. Survivors, victims of a lack of due process, and campus administrators have all told me that the current approach does a disservice to everyone involved,” DeVos said last September when she announced changes were coming.

Sen. Patty Murray, the top Democrat on the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, in a statement said it is “shameful and appalling” that DeVos would issue a rule that would make it harder for assault victims to seek justice.

“Survivors spoke to Secretary DeVos and urged her to not allow campus sexual assault [to] be swept under the rug once again. It’s high time Secretary DeVos listen to them, abandon this plan, and start taking meaningful steps to address our nation’s campus sexual assault crisis,” Murray said.

An Education Department spokesperson declined to comment to the Times Wednesday, saying officials are still deliberating and any information the paper had was “premature and speculative.”

An interim policy, released last September, instituted perhaps the biggest change included in the new proposal: allowing schools to determine what level of evidence they’ll require to determine an assault occurred.

The now-overturned Obama-era regulations required schools to use a lower “preponderance of the evidence” standard, rather than a more stringent “clear and convincing” mandate.

Changing evidentiary standards, particularly at the start of the school year, when most assaults occur, creates uncertainty for survivors of assault and could open the door to lawsuits by perpetrators who were convicted under different standards, experts told The 74 last year.

Other changes, according to the Times, include:

1. Only formal complaints must be investigated. Standards in place since 2001 required schools to investigate anytime the school knows, or reasonably should know, about harassment. The proposed regulations would require investigations only of complaints made to “an official who has the authority to institute corrective measures,” the Times reported, quoting the proposed regulations.

2. Only events on campus must be investigated. The Obama administration required schools to investigate all allegations made by students, but the DeVos rules would require investigations only of events that occurred within their own programs or on their campuses.

3. Victims and perpetrators could request information and cross-examine each other: The Obama administration had discouraged schools from allowing parties to question one another, arguing that it could be more traumatic for the victim.

4. Mistreatment of the accused could constitute sex discrimination. Previously only schools’ mishandling of alleged victims could constitute a Title IX violation.

The proposal would still have to go through a formal notice and comment period, after which the department would release a final version. There is at least one lawsuit, brought by women’s groups, attempting to block the department’s interim policy.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)