Survey Provides ‘Moving Picture’ of Pandemic’s Turbulent Impact on Families With Young Children

Pandemic-related financial hardships on families with young children are creating a “chain reaction” of negative effects at a time when many preschoolers are preparing to return to child care or enter school for the first time, according to new data from an ongoing study.

Specifically, parents who struggle more financially are reporting more behavior and emotional problems in their children.

Those are among the latest findings of a weekly survey of roughly 1,000 parents with young children — a research study capturing the turbulence in families brought on by the pandemic with results published almost as fast as mask requirements change.

Called Rapid Assessment of Pandemic Impact on Development – Early Childhood, or RAPID-EC, the work is led by University of Oregon psychology professor Philip Fisher. The researchers began conducting the survey in early April, and since May they have published weekly highlights. Beginning in August, the survey will be conducted every two weeks.

“There really isn’t a scientific knowledge base of what families are likely to be experiencing in light of a global pandemic,” said Fisher. “We felt like we really needed data that could inform policy decisions.” The challenge, he added, was having a “high-frequency” survey that was also scientifically rigorous and “allows us to get a moving picture of overall well-being.”

With many young children now facing an uncertain beginning to the school year — perhaps starting a new preschool or kindergarten class via Zoom or with a packet of activities — the findings can help educators and program providers gain a better understanding of the conditions in which at-home learning is taking place.

“Policymakers need to hear what’s happening on the ground right now. The impact of the pandemic has been immediate; the data needs to be, too,” said Bethany Robertson, co-publisher and co-director of Parents Together, a parent-led organization that provides tips and resources to families but also works to make parents’ voices part of policy conversations.

Fisher’s team partnered with Parents Together to recruit families for the survey. The researchers aim for a sample of no fewer than 1,000 per week. And while parents have the option of participating more than once, Fisher found that a lot of the “repeat customers” tend to be more affluent and white. To capture more diversity, the researchers select a larger sample than needed and invite more diverse families to participate.

So what are some of the other major findings so far?

First, conflict has increased among all families in the sample, regardless of income. And more than half of the respondents answered that parent-child conflict is on the rise. Families in lower-income homes said financial relief, such as assistance with rent or other housing expenses, would make their situations better, while those in middle- and upper-income homes said they needed more social-emotional support.

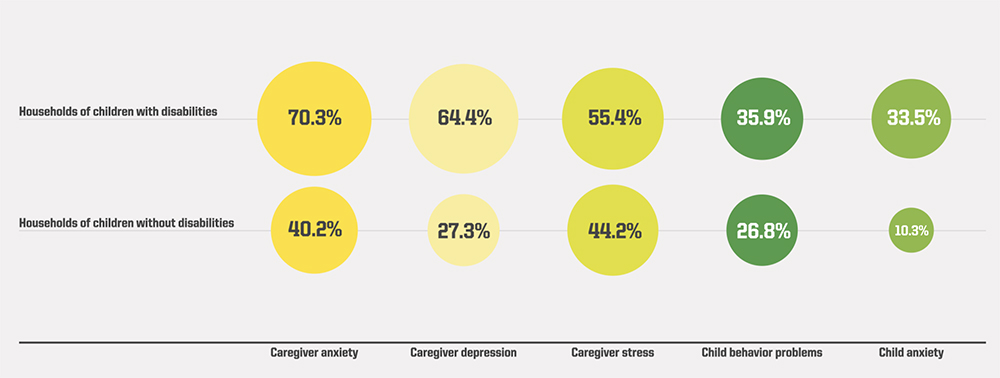

In another recent post, parents or other caregivers in low-income homes, those with three or more children, and those who have a child with a disability are reporting higher levels of depression and anxiety.

Lower-income households and Black and Latino families are experiencing more financial hardship, such as lost income and difficulty covering expenses like housing, utilities and food, the results show. With many eviction bans imposed in the early days of the pandemic beginning to expire, researchers predict large increases in homelessness. The findings have implications for school attendance and students’ ability to use technology for learning.

“Once people can be evicted, we’re going to see a lot of families with young children out on the street,” Fisher said.

‘Mirroring the trends’

Each RAPID-EC post with new data includes recommendations for policymakers and suggested research articles. The project represents a new approach to conducting research. Rather than waiting to publish findings in an academic journal, the team is hoping to provide useful data to state and local leaders so they can respond more quickly to trends. The audience for the results includes officials in education departments, human service agencies and those in nonprofits that work with families. The researchers are also hoping to reach state legislators with their findings.

In fact, each new release often confirms top pandemic-related news stories of the day, said Joan Lombardi, who chairs the project’s national advisory team.

The project is “mirroring the trends, but it’s providing more than anecdotal information,” said Lombardi, who led child care and early-childhood development initiatives at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services during the Clinton and Obama administrations. She currently advises philanthropies focusing on early childhood.

Miriam Calderon, early learning system director with the Oregon Department of Education, said leaders have shifted from approaching the coronavirus as “an emergency that’s going to go away” to thinking about how to adapt early learning programs and other efforts for young children. “All of these services have to coexist with COVID for the foreseeable future,” she said.

The survey data, she said, have prompted her and others in the department’s early learning division to ask questions about services at the local level, such as whether families are still taking their children for regular checkups, vaccinations and developmental screenings. One of the survey’s national findings was that more than a quarter of families skipped a doctor’s visit for a healthy child this past spring.

David Mandell, the director of policy and research in the division, added that the results provide a valuable connection to parents as leaders grapple with what it would take to make them feel it’s safe enough to bring their children to school or a center.

‘Very basic needs’

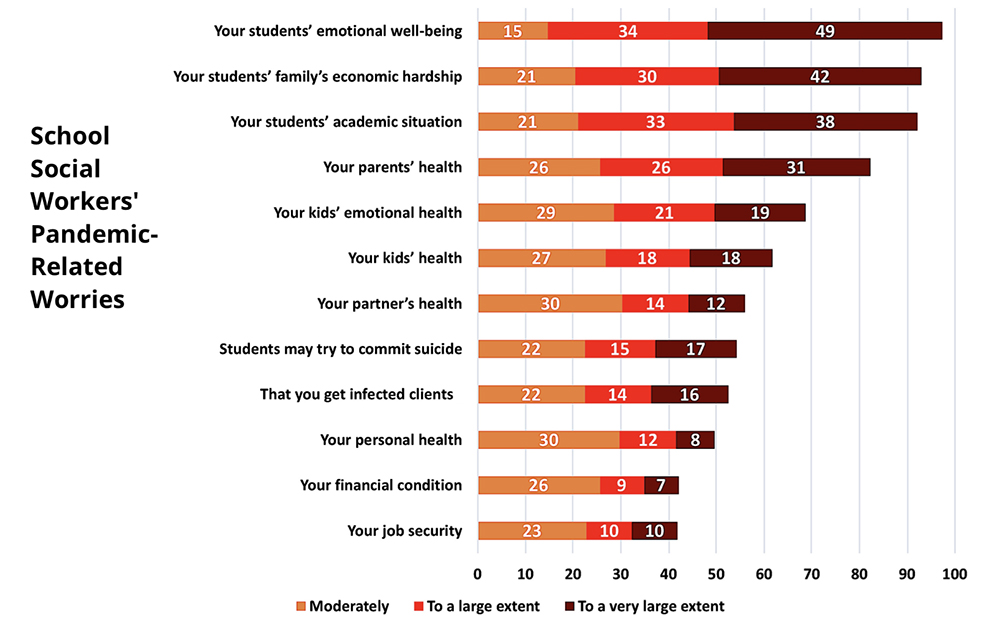

The trends emerging in RAPID-EC echo other surveys of those working within school districts to respond to families’ and children’s basic needs. In a recent survey conducted by researchers at four universities, three-quarters of school social workers responded that at least half of the students in their schools need mental health services, more than 60 percent said at least half don’t have enough to eat, and more than 40 percent said at least half of the families in the schools they serve need support with staying in their homes.

“There has been much discussion pertaining to online delivery of instruction, services, and education,” the authors of the survey report wrote. “More needs to be focused on how the pandemic has affected the very basic needs for human existence in low-income schools that serve students of color.”

And Parents Together, which reaches families with a wider age range of children, released its own survey results last week showing that 45 percent of families are somewhat or very concerned about losing their homes, with more than half cutting back on other expenses, such as food and medicine, to cover rent or mortgage payments.

“When we first started calling for rent freezes a few months ago, this wasn’t a part of the national discussion,” Robertson said. “Now, as 23 million folks face possible eviction by the fall, we’re seeing some policymakers interested in what we can do to keep families in their homes.”

Last week, for example, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey extended the state’s eviction ban through the end of October. At the federal level, a bill passed in the House and legislation introduced in the Senate aim to extend eviction bans through early next year.

Evictions contribute to chronic absenteeism and occur at higher rates in lower-income neighborhoods where schools have higher percentages of nonwhite students, studies show. An analysis conducted in Richmond, Virginia, for example, noted that as housing prices in some areas of the city tilt upward, it can be harder for a family with a past eviction to get a lease.

The researchers wrote that as the demand for housing increases, evictions create instability not only for families but also for schools.

Back in Oregon, Calderon said the RAPID-EC data are also guiding Gov. Kate Brown’s new Healthy Early Learners Council, which is focused on reopening child care and early learning programs. Addressing “challenging behaviors” and preventing suspension and expulsion of young children will be one aspect of the council’s work.

With many programs and schools expected to be operating both in-person and remotely, Calderon said data on how the pandemic is affecting access to child care and family well-being will continue to be important. One finding in the data was that almost half of the respondents said they had lost the child care arrangement they had prior to the pandemic.

“I don’t think people acknowledge enough that public school is a form of child care,” she said. “When school is closed, someone in the family isn’t working.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)