Report: Deck Stacked Against Young Children of Color, but Leaders Can ‘Seize This Moment’ to Improve Equity

Harsh discipline like corporal punishment, separating preschoolers with disabilities from their peers, and too few high-quality programs for English and dual language learners are among the “structural inequities” holding back young children of color from a successful start in school, according to a new report released Tuesday.

And those disadvantages have only intensified as a result of the pandemic and the national protests over police violence, wrote the 15 contributors from 11 universities and organizations who authored the study.

“Our systems have created barriers that stack the deck against many children — and they have to climb over those barriers before they are out of diapers,” the report said, calling on national, state and local leaders to “seize this moment as an opportunity for positive change.”

Published by the Children’s Equity Project, based at Arizona State University, and the Bipartisan Policy Center, the “Start with Equity” report offers a policy agenda that includes a ban on punishments that exclude children from classrooms, more early-childhood mental health services, full funding for special education, incentives for including children with disabilities in regular classrooms, and assessment tools in multiple languages.

And it calls for government studies on questions related to the three central topics of discipline disparities, inclusion of students with special needs and services for young English learners.

“We don’t pretend to say that if you solve these three, then we’re good,” said Shantel Meek, the founding director of the Children’s Equity Project. She added that the report is meant to push leaders toward focusing on outcomes that can be measured. “Before George Floyd, we were talking about equity, but it was kind of ambiguous. Our whole approach is, let’s get it concrete and actionable.”

‘A new pair of glasses’

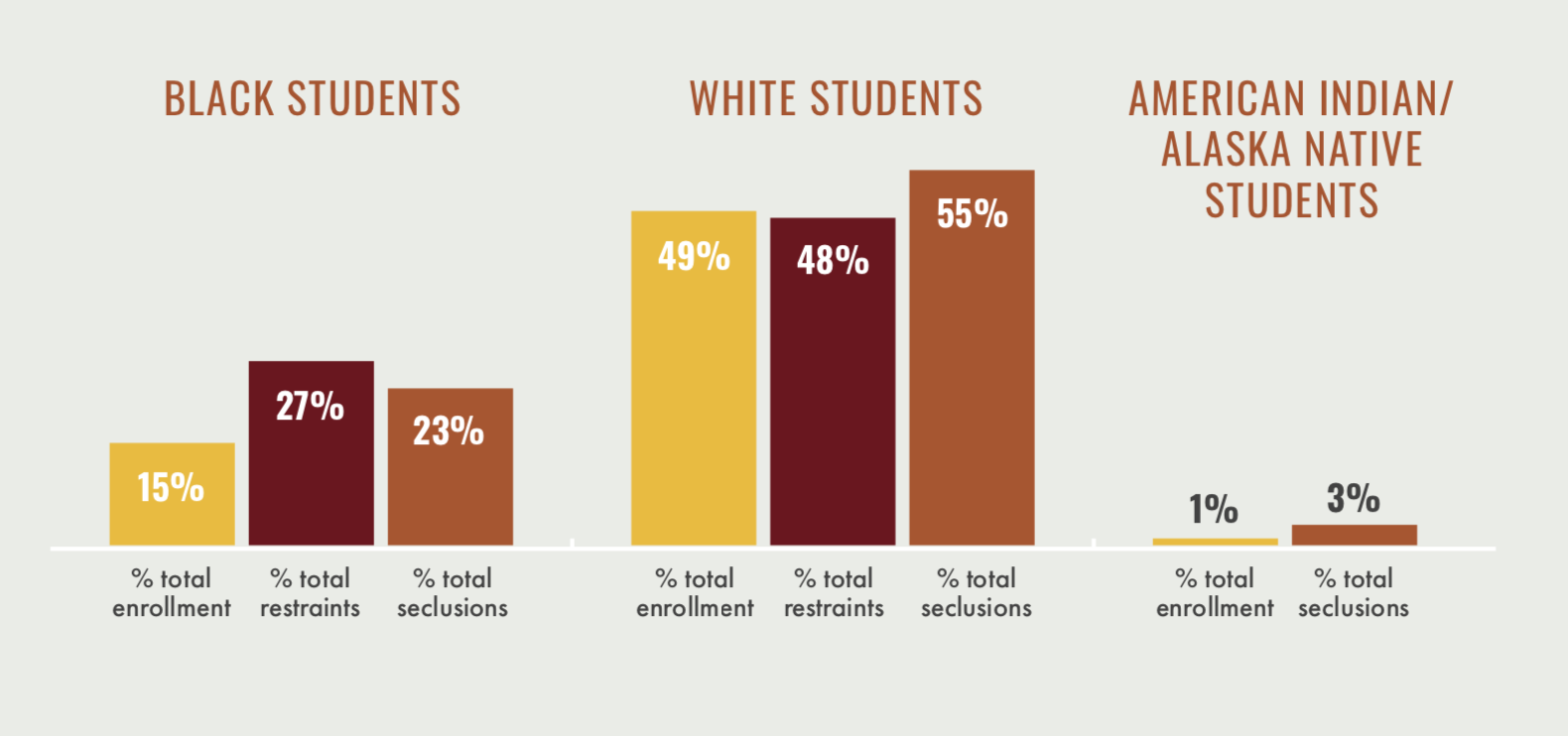

The report is also packed with data on policies that can contribute to negative early school experiences. Corporal punishment in schools, for example, is still legal in 19 states, with cases more common in Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi and Texas. Black children make up 15 percent of children in K-12 schools but represent almost 40 percent of those who are suspended at least once, the report said.

“There is no evidence that Black children show greater or more severe misbehavior,” the authors wrote. “Instead, research suggests Black children are punished more severely than their peers for the same or similar behaviors and that they are subject to increased scrutiny as early as preschool.”

Meek points to Arkansas as one state that has addressed discipline issues by having child care providers sign a contract agreeing that in order to receive federal child care funding, they won’t expel or suspend a child.

The report urges districts to increase teacher training on positive discipline and methods that help them change their assumptions about children of color.

One such event is taking place this week, with more than 1,100 educators virtually attending Reimagining Education, a four-day institute devoted to creating more integrated schools.

“We just try to get people to stop and put on a new pair of glasses,” said Amy Stuart Wells, a sociologist and desegregation researcher at Teachers College, Columbia University, who began the summer program in 2016. She felt that the desegregation field focused too much on the demographic makeup of schools and not enough on curriculum, instruction and school culture. “It’s easy to talk about putting kids on a bus, but it’s harder to talk about what you do when they get off the bus.”

Implicit bias training, which many districts have pledged to implement since the protests over George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, can be “one-off things,” especially if teachers think the training doesn’t apply to them, she said. “We get people to reimagine. What are the things you take for granted that maybe you should question?”

Creating a ‘parallel track’

The report’s three policy areas have the common theme of exclusion, Meek said. In special education, the report notes, more than half of preschoolers with disabilities still attend early-childhood classrooms separate from peers without disabilities, even though research points to the benefits of inclusion. And in 13 states, children of color with disabilities are in regular classrooms at lower-than-average rates.

“The benefits of inclusion depend on children being included several days per week across social and learning experiences and simultaneously receiving individualized instructional strategies, alongside peers with and without disabilities,” the authors wrote.

They also note that although enrollment in state-funded pre-K programs has grown over time, that doesn’t signal a corresponding increase in children with disabilities in those classrooms. Instead of integrating children with special needs into regular classrooms, some states create or expand separate programs. “This parallel track is often lower in quality and has limited access to the general curriculum,” the report said.

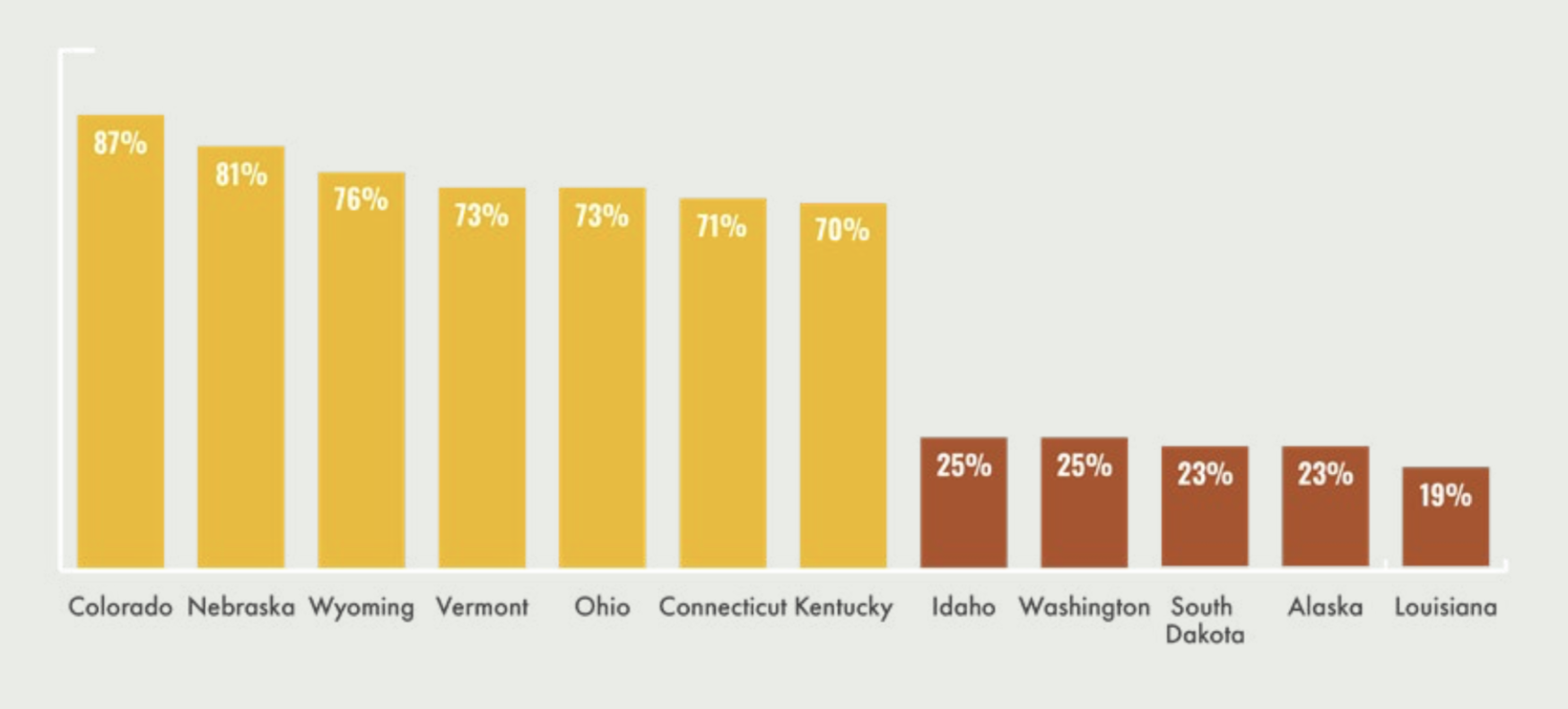

W. Steven Barnett, senior co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research, listed Massachusetts, Kentucky, Connecticut and New Jersey as states that have made inclusional pre-K a priority. In some New Jersey districts, he said, special education preschool teachers even worked across multiple classrooms when all children were integrated into regular classrooms.

But the report notes that states with large pre-K programs, such as Florida and Oklahoma, have smaller percentages of children with disabilities in regular classrooms.

‘Make or break’

Finally, the report notes that children learning both English and their home language at the same time — known as dual language learners — now represent almost a third of children under age 8 in the U.S.

Research shows that children benefit academically and socially when growing up with two languages. And while dual language immersion programs are growing — allowing children to become fluent in English and a second language — young English learners sometimes don’t have access to them.

“For [dual language learners], bilingual learning in education is not an optional opportunity for enrichment,” the authors wrote. “Rather, it can make or break their access to a quality education altogether.”

The report points to Head Start as having strong standards that recognize the language needs of dual language learners, but it’s unclear how many programs are following through on implementing those standards, Meek said.

In K-5, Meek said, there are district-level examples of strong programs, such as the Portland Public Schools in Oregon and the Chula Vista Elementary School District in California. But the report notes that no state has developed a comprehensive plan related to dual language learners in preschool or the elementary grades.

The authors conclude by saying that the goal of interventions is often “‘fixing the child,’ as opposed to fixing systems,” and that many schools and early-childhood programs are still not prepared to educate children from diverse backgrounds.

“Child advocates have a larger and more daunting task ahead in a post-COVID-19 world,” they wrote. “Intentionally focusing on policies, practices, and investments that support more equitable systems for our youngest learners is a starting point.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)