Study: Teacher Coaching Can Boost Instruction and Student Achievement. But Can It Be Scaled Up?

One-on-one teacher coaching generates meaningful improvements to both classroom instruction and student achievement, according to a newly published meta-analysis of existing research.

But there’s a tricky caveat: Efforts to expand coaching programs on a wider scale might only dilute their value, the authors find.

The review offers some hopeful evidence in the ongoing debate around the efficacy of teacher professional development. Recent studies have suggested that school districts realize sparse returns from the billions of dollars and dozens of school days they invest each year on skills workshops, planning sessions, and summer seminars for teachers.

Written by Brown University’s Matthew Kraft and the University of Maryland’s David Blazar, the paper compiles the results of 60 studies conducted since 2006 that examine the impact of teacher coaching on either instruction (as measured by scoring rubrics like the Classroom Assessment Scoring System or the Early Language and Literacy Classroom Observation) or student academic performance (as measured by standardized tests).

Coaching typically involves teachers being observed in the classroom and later receiving feedback from peers, administrators, or master teachers. Kraft and Blazar focused their analysis on studies of one-on-one programs that were conducted regularly (at least once every few weeks) over an extended period of time and geared toward the cultivation of specific skills.

On balance, they found that coaching programs tend to enhance both the quality of teaching and student achievement, though the former much more than the latter. In a conversation with The 74, Kraft said that improvements to instruction are filtered through a long set of conditions before they can change student performance in measurable ways. Some coaching programs, for example, are geared toward developing non-academic student outcomes, such as classroom engagement or social and emotional learning.

In coaching, “you first need to develop teachers’ understanding of pedagogical content knowledge,” he said. “Then you need to get them to implement that new knowledge in a way that’s effective in class, and those changes have to be large and consistent enough to increase student understanding and learning. And those students then have to demonstrate that increase in learning in a format that’s captured by state standardized tests. And that increased learning has to be on content that’s covered by state standardized tests.”

“So there’s multiple points at which you could see slippage along that causal chain,” he said.

Still, the impact on student achievement of implementing an effective coaching regime compares favorably with other reforms, such as student academic incentives, merit-based pay, and extended learning time, the authors write. The benefits to instruction are described as larger than the difference in quality between a novice teacher and a more experienced colleague.

High-quality programs tend to combine group training sessions with individual consultations between teachers and coaches. In terms of student achievement, content-specific programs seem to work better than generalized coaching. “General coaching programs are often focused less on helping teachers improve students’ test scores and more on developing teachers’ abilities to support students’ social and emotional development,” the authors write.

Somewhat surprisingly, quantity matters less than quality. The studies show that more hours of coaching aren’t correlated with greater effects.

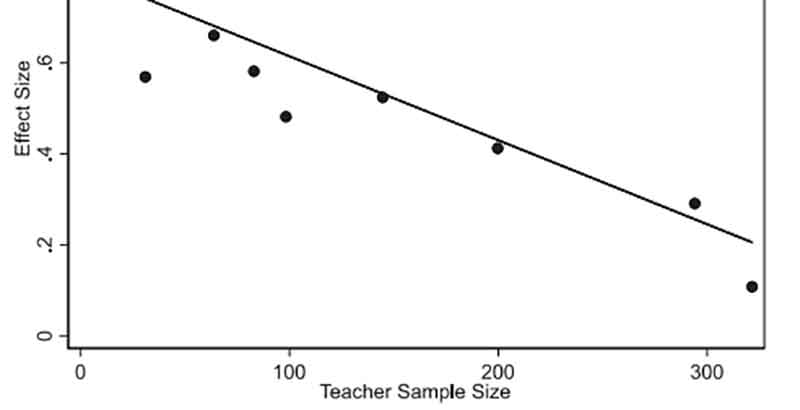

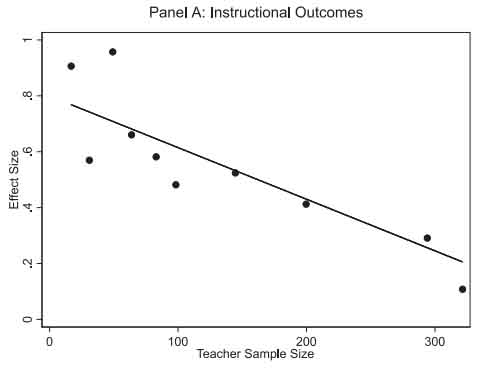

But the most important variable is clearly size. Expanding a coaching intervention is consistently shown to limit its effectiveness. Kraft and Blazar separated the programs into smaller examples (less than 100 participants) and larger ones (more than 100). The smaller programs’ impact on instruction was nearly double that of larger programs. For student achievement, smaller programs were nearly three times as effective.

Scalability, the hobgoblin of education reform efforts, is at work again. It’s difficult to recruit and train large numbers of teacher coaches, the authors explain. Standardizing the programs across large schools, districts, and even entire states (one study measured a literacy initiative that deployed 2,300 coaches across Florida; results were almost nonexistent) can iron out the flexibility necessary to improve performance among teachers of different skills and specializations.

And coaching works best in school environments that make a lot of room for experimentation and critique. If teachers feel they’re being unduly attacked, or that required coaching is actually a pretext to document their faults and initiate termination, even the best advice will fall on deaf ears.

“The potential challenge is those teachers who are experienced, who have been told by those classic, old-style evaluation systems that they are satisfactory, proficient, or even better at their jobs,” Kraft said. “And then someone comes along and says, ‘We want you to participate in this coaching process that’s going to shine a light on things that someone else thinks you’re not that good at, but you think you are.’ That’s probably one of the hardest conversations to have as a coach.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)