Secessions Have Heightened the Racial Divide Between Southern School Districts, New Research Shows

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

The recent and highly publicized trend of school district secessions has contributed to racial segregation between school districts, according to a new study published in the journal of the America Educational Research Association. Following a community’s decision to secede, segregation along district lines has increased between white and nonwhite students in several counties in the American South, the authors find.

The research shines a new light on the controversial practice of secession, which occurs when one community breaks away from its existing school district to create a new one with different boundaries. The process is often driven by relatively advantaged areas that choose to create a splinter district, leaving behind less affluent communities with suddenly diminished school funding prospects, according to a report released earlier this year by the research and advocacy group EdBuild. Some 128 communities had pursued secession from their districts in the 21st century, the report found.

The study published by AERA — co-authored by Pennsylvania State University professor Erica Frankenberg and Virginia Commonwealth University’s Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, along with Kendra Taylor of the research organization Sanametrix — focuses more specifically on the South, where seven counties experienced school district secession between 2000 and 2015. In those counties (Jefferson, Marshall, Montgomery, Mobile and Shelby counties in Alabama; East Baton Rouge Parish in Louisiana; and Shelby County in Tennessee), a total of 18 new school districts were created during that period.

In recent decades, Southern school districts have been comparatively less segregated than those in other areas of the country, largely as a result of court orders compelling many to reduce racial homogeneity in the wake of the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling. In the seven Southern counties in question, the authors noted that the aggregate public school population was much more diverse than the Southern region as a whole (generally defined as the 11 states that made up the Confederacy): Between 2000 and 2015, the white percentage of public K-12 students in those counties fell from 42 percent to just 32 percent, compared with a decline from 54 percent to 43 percent throughout the entire South over the same time.

In an interview with The 74, Frankenberg said that her interest in the topic stemmed partially from personal experience.

“One of the reasons I find this interesting is that I grew up in Mobile County, which is one of the districts where secession has taken place,” she said. “Two of the three towns that seceded were overwhelmingly white. And so you suddenly no longer had those students as part of the pool from which you could conceivably create more integrated spaces.”

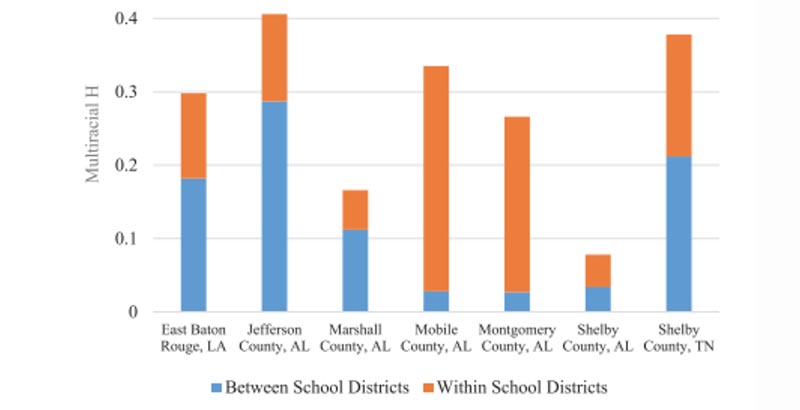

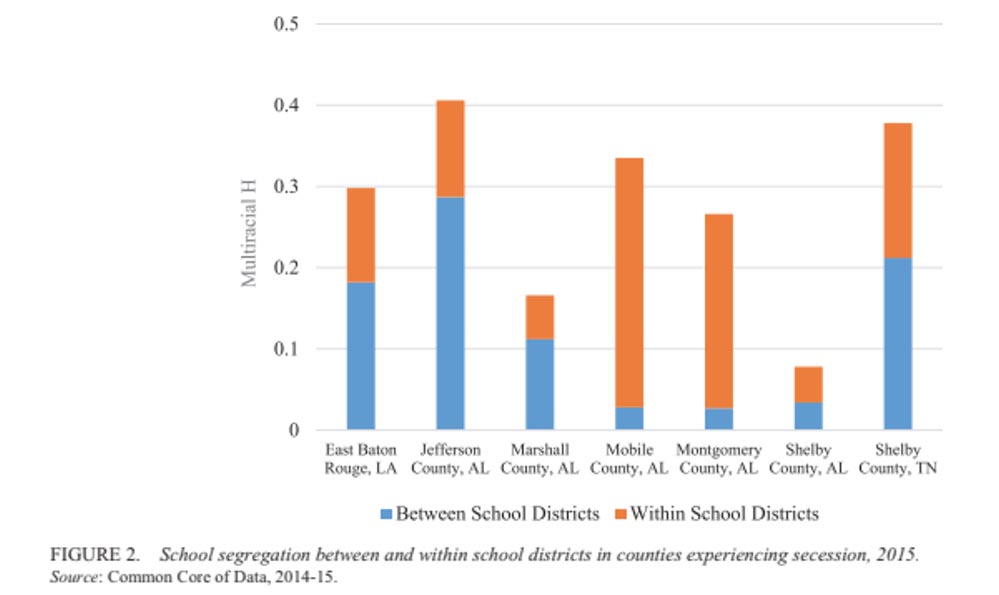

Indeed, by examining levels of racial segregation in those seven counties at the level of U.S. census blocks, Frankenberg and Siegel-Hawley found that, following secession, school district boundaries were responsible for much greater shares of racial segregation between students.

In 2000, they calculate, district boundaries contributed to 60 percent of total segregation between black and white students; 15 years later, they accounted for 70 percent of segregation between those groups. Similarly, district boundaries accounted for just 37 percent of segregation between white and Hispanic groups in 2000, rising to 65 percent in 2015.

In other words, segregation in these counties is increasingly occurring between, rather than within, school districts.

That’s an important development because of the historical difficulty of moving students across those district boundaries. Many Southern districts have traditionally been organized on the “one-county, one-district,” model, ensuring that white parents couldn’t simply move to another part of their metropolitan area to pull their children out of diverse schools. Since few policy levers exist in the South to move students across districts (charter schools, for instance, did not exist in Alabama until 2015, the last year included in the study), Frankenberg noted, the increasing association of school districts with more homogeneous racial communities is an ominous trend.

“Really, one could think about the creation of these new school districts as a form of school choice,” she said. “[Seceding communities] were choosing to create districts to exercise control over the resources of that district, as well as over decisions of who could attend and who couldn’t. Some people have been able to enact choice, and then there are some who are left behind, which may or may not be fully understood.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)