New Survey: Teachers Report Widespread Student Behavioral Disruptions but Sharply Diverge on Whether Consequences Demonstrate Racial Bias

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

American schools are undergoing a dramatic shift in their approaches to school discipline, as states and districts have worked over the past few years to reduce student suspensions under federal guidance issued by the Obama administration. The results of a new survey released today show that teacher perceptions of the transformation are mixed.

According to the survey, conducted in 2018 by the right-leaning Fordham Institute, most teachers believe their schools’ disciplinary policies are inconsistently enforced. A sizable majority said that the learning of most students was harmed by the presence of a small number of misbehaving classmates. And teachers in high-poverty schools were especially likely to encounter behavioral problems like violence and disrespect.

The report comes at a time when education leaders and politicos alike are debating where discipline policy should go from here. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos formally rescinded the Obama-era recommendations in December, claiming that they forced educators to ignore disruptive behavior in the classroom. Many conservatives have argued that the guidance was a bureaucratic overstep.

But eliminating it raised hackles among activists, who point to evidence that minority students are more likely to be severely punished for disciplinary infractions than white students. Just last week, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights released a lengthy report warning of racial disparities in suspensions and urging the federal government to be vigilant against civil rights violations.

Meanwhile, teachers’ own attitudes have been difficult to gauge. According to a 2018 poll from the journal Education Next, just 29 percent of K-12 teachers supported federal policies that prevented schools from suspending or expelling black or Hispanic students at higher rates than other students. But that doesn’t mean they relish the idea of removing students from the classroom: Another 2018 poll, this one conducted by the advocacy group Educators for Excellence, found that only 39 percent of teachers agreed that suspending or expelling students was an effective means of improving behavior; instead, most said they favored rewarding positive behavior.

Fordham’s survey, administered by the nonpartisan RAND Corporation, asked roughly 1,200 teachers around the country for their impressions on student behavioral problems and various methods of addressing them. Their responses, many of which complain of distracted classrooms and a lack of administrative support, may prove concerning to those who are charged with weighing the balance between fostering strong learning environments and protecting the rights of all children.

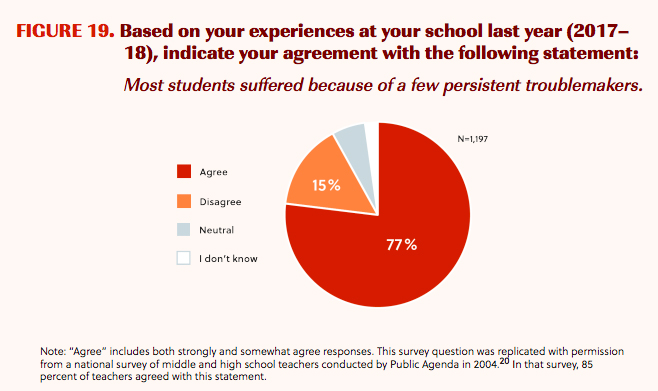

In all, 77 percent of teachers said they either “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed that most students at their school were impeded in their learning because of the actions of a comparatively small number of misbehaving classmates. Among those working in high-poverty schools (i.e., those where at least three-quarters of students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch), 64 percent said they were teaching at least one student with a chronic behavioral problem.

While many teachers cited concerns with how their schools approached student misbehavior, a clear split emerged between teachers at high-poverty schools and those working in schools where less than 25 percent of students qualified for free lunch. While 32 percent of teachers at high-poverty schools said that physical fights occurred in their workplace daily or weekly, just 5 percent of teachers at low-poverty schools said the same. Four percent of teachers in low-poverty schools said they had been physically assaulted over the previous school year, compared with 13 percent of teachers who said they had been attacked in high-poverty schools.

Report author David Griffith, a senior research associate at Fordham, said that the national discourse around school discipline too seldom reflected the disconcerting realities in under-resourced schools; highlighting them, he said, will hopefully bring about “a more honest conversation about how we tackle these challenges.”

“Our general feeling was that the conversation around school discipline was a little divorced from reality, and what we were hearing from teachers was very different from what we were hearing from people who were more physically removed from the problem,” he said.

Of note, roughly equivalent percentages of white and black teachers pointed to the same levels of classroom danger and disruption. That suggested teacher perceptions were a product of their work environments as opposed to racial bias, Griffith noted.

Disagreements on ‘racial bias’

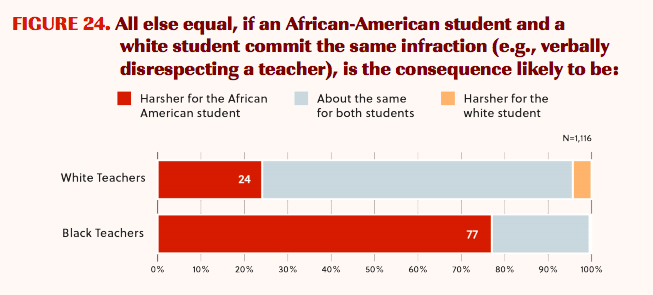

Still, black and white teachers differed significantly in their views of the role racial bias plays in determining disciplinary consequences. Just 24 percent of white teachers said that, all else being equal, a black student would be punished more harshly than a white student for the same behavioral infraction. But fully 77 percent of black teachers said they believed the black student’s punishment would be more severe.

The split reflects a clear difference in the education community over how much disparate rates of suspension and expulsion can be explained by teachers’ conscious or unconscious racial biases.

The recently released report from the Commission on Civil Rights states, in no uncertain terms, that minority students “do not commit more disciplinable offenses than their white peers — but black, Latinx, and Native American students in the aggregate receive substantially more school discipline than their white peers, and receive harsher and longer punishments than their white peers receive for like offenses.”

There is research evidence indicating that teachers are more likely to deem black students “troublemakers,” or suggest that they be suspended, than white students. A report last year found that black students in New York City are more likely than students of other racial groups to receive harsh punishments for eight of the top 10 offenses accounting for the vast majority of student suspensions. Black students suspended for “reckless behavior” were held out of school for an average of 16.7 days, for instance; Asian students were suspended for just 7.3 days for the same offense.

But the Commission’s statement goes further than the widely acknowledged reality that minority students are more likely to be subject to school discipline than white students, or even the more contentious claim that implicit racial bias is sometimes at play in determining suspensions and expulsions. If students of all racial and ethnic backgrounds truly commit behavioral infractions at the same rate, then many would conclude that racism must be to blame for most or all of the significant disciplinary disparities between white and nonwhite students.

News accounts of the report have zeroed in on such claims, and one dissenting member of the commission has written that attributing disparate discipline rates to faculty bias “stokes racial resentment and erodes personal responsibility.”

Concern over possible civil rights violations against minority students has led to both district- and state-level policies aimed at bringing down suspension rates. Out-of-school suspension is seen as particularly problematic, as it keeps kids out of the classroom without providing access to alternative learning opportunities.

Research has shown that suspension rates have dropped in some jurisdictions since the Obama-era Education Department issued its disciplinary guidance in 2014. In Fordham’s survey, 41 percent of teachers said that suspensions had indeed declined in their schools over the previous years, compared with 14 percent who said that they had increased.

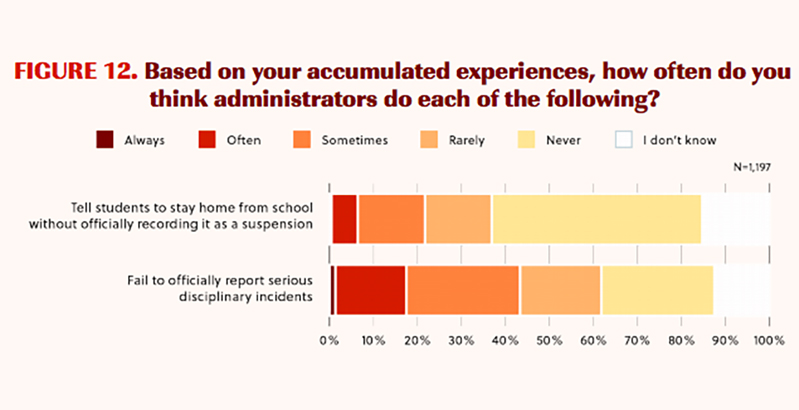

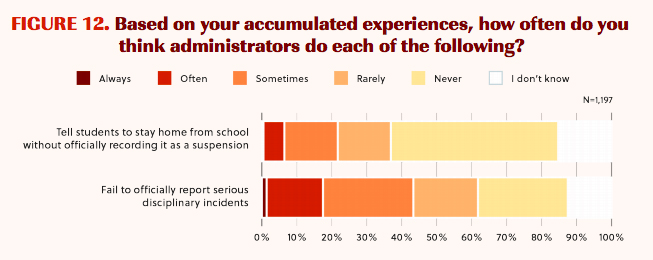

But teachers who said they’d observed a decrease in suspensions were divided about the cause. Most said that the use of new alternatives to out-of-school suspensions were at least somewhat responsible, but 48 percent said that the underreporting of suspensions (for instance, if a student is told by an administrator to stay away from school for a number of days but is not formally suspended) was a contributing factor.

Asked whether they believed school administrators ever neglected to report “serious disciplinary incidents,” 43 percent said they did.

Still, many teachers said they saw the promise in new alternative approaches to discipline, including “restorative justice” systems that encourage student-led conflict resolution. More than half of all respondents said they found approaches that attempted to diagnose and treat student trauma as a root cause of misbehavior to be “very effective,” for instance.

Fordham’s Griffith said that the results of the survey make clear the need for greater resources devoted to addressing disciplinary policy, such as more money for social workers and student counselors. For too long, he said, policymakers had treated the issue as “a cheap problem.”

“We need to stop doing this on the cheap, and I hope that local leaders will think about how they can help teachers and what additional resources would be helpful,” he said. “I think the answer is to have a fact-based, thoughtful conversation, because that’s the only way forward.”

Disclosure: Kevin Mahnken was an editorial associate at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute from 2014 to 2016.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)