New Study: Multilingual Students Have Made Huge Progress on NAEP Since 2003

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

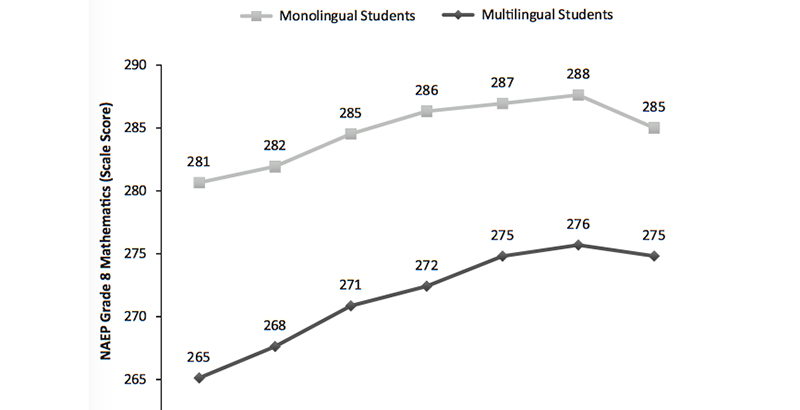

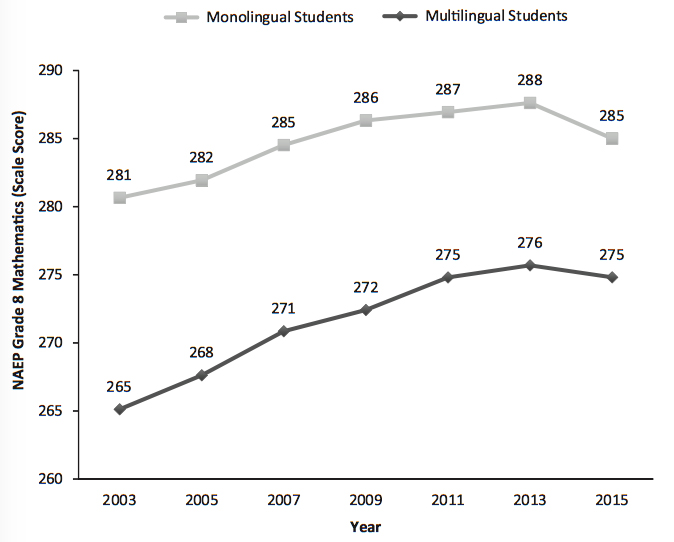

Research published today suggests that multilingual fourth and eighth graders have made huge strides over the past 15 years on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, commonly referred to as “the nation’s report card.” Students who speak a language other than English have considerably narrowed the gap in both math and reading scores with those who speak only English, the study reports.

The findings hinge largely on the authors’ framing of student categories: In most prior research and news accounts, English learners have lagged far behind their native-speaking classmates in NAEP performance.

But some experts have recently argued that measuring scores this way is deceptive, since the top-performing multilingual students gradually attain proficiency in their adopted language and lose the “English learner” classification. By measuring and reporting the scores of only current English learners, therefore, NAEP is tracking the performance of students who either have only recently begun studying the language or experience greater than usual trouble in learning it.

Instead, study authors Michael Kieffer of NYU and Karen Thompson of Oregon State University looked at the scores of students who reported that people in their home spoke to one another in languages other than English. That included students who were brought up bilingual, as well as those who eventually aged out of “English learner” status.

“By looking at this larger group of multilingual students, we can capture the success of students who were English learners but then became reclassified as what we call ‘former English learners,’ ” Kieffer told The 74 in an interview. “When we do that, we find a different story.”

That story is decidedly cheerier than what we might expect given the overall stagnation in NAEP scores since roughly the time of the Great Recession. Between 2003 and 2015, the scoring disparity between students from multilingual or non-English households and those from solely English-speaking ones was narrowed significantly: Fourth-graders closed the gap by 24 percent in reading and 37 percent in math, while eighth-graders caught up by 27 percent in reading and 39 percent in math.

Overall, the authors estimate that multilingual students’ progress amounts to somewhere between one-third and one-half of a school year. While the scores of monolingual English speakers have also climbed somewhat since 2003 and remain higher overall, they have only improved by one-half or one-third the number of NAEP points as multilingual students.

The long-standing method of specifically measuring students who are presently learning English, rather than grouping them alongside those who were once English learners but eventually gained proficiency, stemmed from noble intentions, Kieffer argues.

In 1974, the Supreme Court ruled in the landmark case of Lau v. Nichols that a lack of supplementary language instruction in public K-12 schools was a violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Following that ruling, Kieffer says, advocates focused on the provision of services — such as access to core curricular materials in a language that can be understood — to students struggling with burdensome linguistic challenges.

But in “keep[ing] the focus on the students who need the services … they have almost intentionally skewed the data in inappropriate ways.”

“That’s the civil rights principle, and one that I deeply believe in and think is very important. But what happens is that by overly focusing on that subgroup, you miss out on this bigger-picture question,” Kieffer says.

Although the study argues that the prevailing view of multilingual students — academically struggling, and making little progress on standardized tests — is a misconception, it is less clear why these students have improved over the past 15 years. Kieffer and Thompson give credit to No Child Left Behind, the federal law that linked school-level accountability with the performance of student subgroups. But they add that demographic changes may have played a role as well.

“It’s no longer an exception to the norm to have a student who is in the process of learning English,” Kieffer says. “Now it’s the norm to have many students who are learning English, and that may incentivize and encourage educators to attain new schools and try out new strategies and techniques and do things a little differently.”

Go Deeper: This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. See our full series.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)