New South Carolina Study of Public Montessori Schools Shows Majority Low-Income Students Outperforming Peers

A five-year study analyzing the impact of South Carolina’s nearly 50 Montessori public schools has found that their students perform significantly better than those in traditional public schools, closing the achievement gap especially for children from low-income backgrounds.

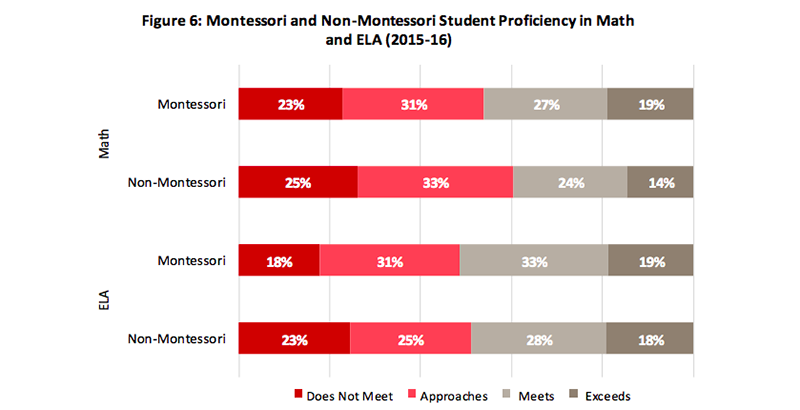

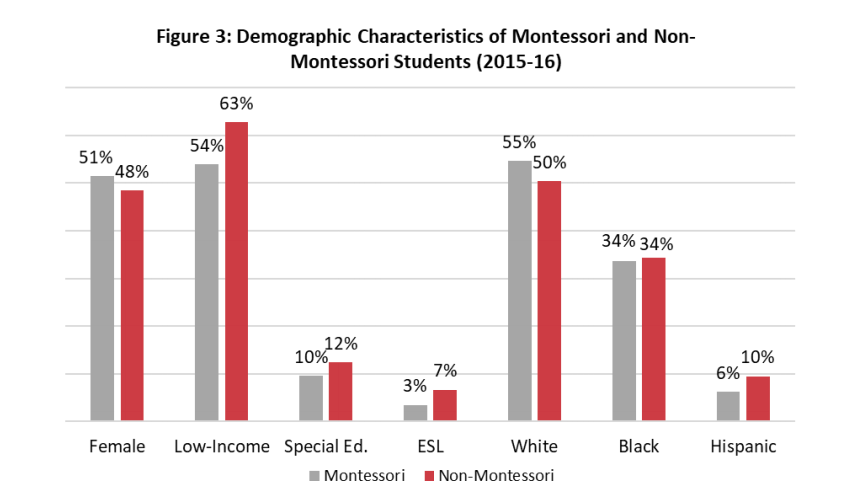

Montessori students demonstrated more growth in reading and math, earning state test scores that were 6 to 8 percentage points higher. But they also bested their non-Montessori peers in the soft skills inherent to Montessori education: creativity, good behavior, and independence.

In their analysis of subgroups, the researchers looked at three years of growth across gender, race, and poverty, and matched the scores of children in Montessori schools with non-Montessori students to compare and eliminate selection bias. Low-income, non-low-income, black, white, male, and female students in Montessori schools were all subgroups that showed significantly more progress than their non-Montessori peers. The researchers didn’t find significant differences for Hispanic or “other race” students, but this could be because of the small sample size.

This new research is one of the largest longitudinal studies in a growing body of work showing the positive outcomes associated with Montessori schools. It was funded by the Self Family Foundation and the South Carolina Education Oversight Committee.

“Nationally, we’ve been fighting the achievement gap for years and have found few things that close that gap, so the fact that low-income Montessori kids fared better than their low-income peers… that says a lot,” said Ginny Riga, Montessori consultant for the South Carolina Department of Education.

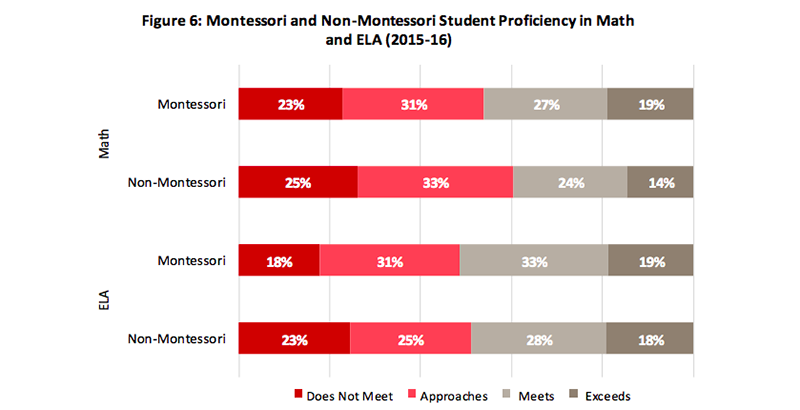

Low-income students make up 54 percent of enrollment in South Carolina’s public Montessori schools, and non-white students account for 45 percent of the population — slightly lower than the percentage in the state’s traditional schools. Researchers said this helps counter a common stereotype that Montessori education is for wealthy white students.

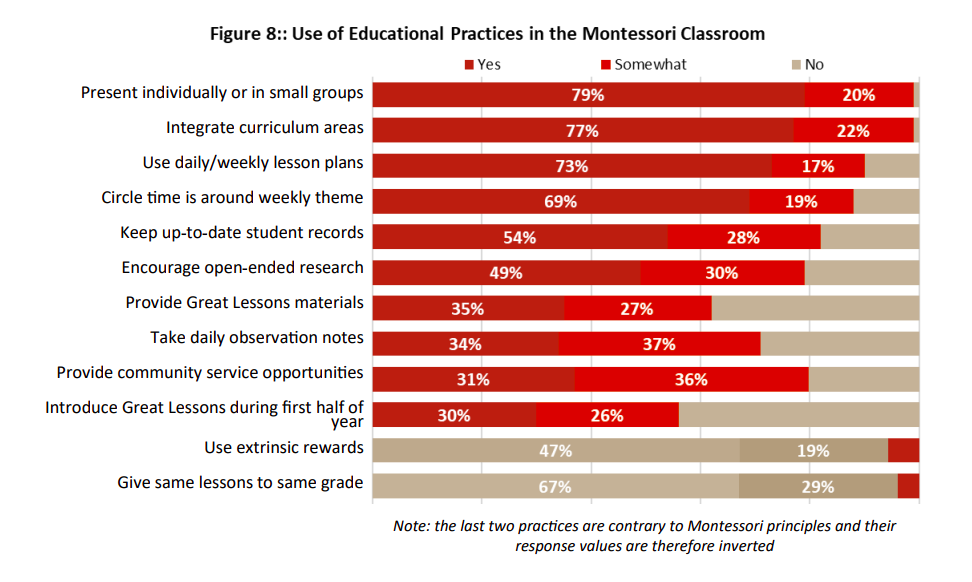

The study was conducted from 2012 to 2016 and included principal surveys and 126 random, unannounced classroom observations. Data from state testing, attendance, discipline records, and a creativity assessment were used to measure academic and soft skills.

“The findings around creativity were interesting as well,” said report author Brooke Culclasure, research director of Furman University’s Riley Institute. “We want to measure these things, and it’s so important, but hard to measure.”

Skills like creativity and independence, more than state test scores, are what’s important to Montessori educators, Riga said.

“It’s hard to measure enjoyment of school and responsibility and independence, but anyone who has worked for any length of time in Montessori will tell you that’s what happens to the children,” she said.

The same goes for the adults — teachers in Montessori public schools are more likely to say they love their jobs than teachers in traditional schools, the study found.

Traditional Montessori education is very personalized, with students choosing their learning materials every day — from blocks to drawing to reading — and teachers acting as guides, observing from the corners of the room rather than presenting lessons.

South Carolina has the largest number of public Montessori schools in the country, at 52, followed by California, with 46, and Arizona, with 42, according to the Montessori Census. Its first public Montessori school opened in the mid-1990s, and in 2004, a supportive state superintendent, Inez Tenenbaum, hired Rigs as the first state Montessori coordinator. Riga said it was the first position of its kind in the United States and signaled state support for public Montessori programs. As of this year, the South Carolina model has grown to 52 school sites serving over 8,500 students, mostly elementary-age.

Researchers first measured how closely schools were adhering to the traditional Montessori model before including them in the study, and found a high rate of fidelity among the state’s schools.

But half of educators believe the authenticity of their model is slipping each year, especially because of standardized testing mandates that require test preparation. Traditional Montessori programs don’t include testing, though all public schools in the state must follow testing requirements.

It’s not easy to open a Montessori school. Startup costs for materials and teacher training are significant, even though they’re a one-time cost.

Organizations like the American Montessori Society help schools with teacher training and accreditation, said the society’s executive director, Tim Purnell.

“This is really a wonderful study in terms of promoting the importance and need of Montessori for all children,” he said. “That’s the key finding here: that we should not be limiting Montessori to communities that can afford it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)