New Research: Diversity Initiative Helps Stave Off Gentrification in Seven NYC Schools

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new numbers, research, and reporting. Go Deeper: See our full series.

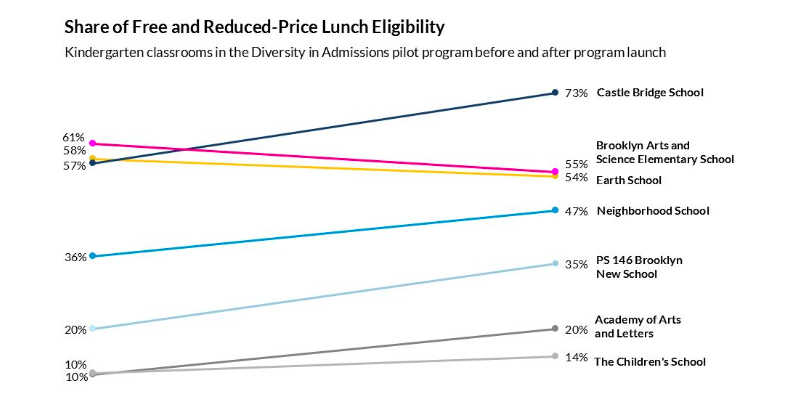

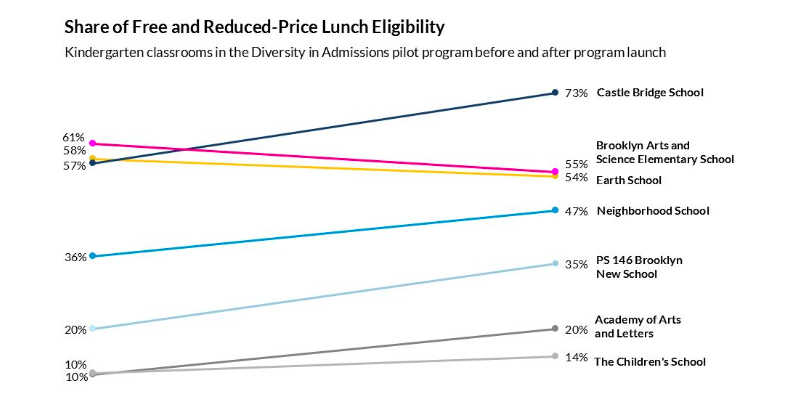

A fledgling initiative in seven New York City schools has shown promising early results in increasing socioeconomic diversity among student populations, according to new analysis by the Urban Institute. After reserving seats for specific groups of children, five out of seven schools saw higher shares of low-income students during the first year of implementation.

The analysis, written by researcher Erica Blom, focuses on the Diversity in Admissions pilot program, which was rolled out by the city in 2016-17. In seven public schools across five separate jurisdictions (although New York City operates as a single district, it is also divided into 32 “community districts”), large numbers of placements were set aside for students from disadvantaged groups in an effort to combat the effects of gentrification.

Most of the once-downtrodden neighborhoods in which the schools are located — like Washington Heights in Manhattan and Fort Greene and Gowanus in Brooklyn — have recently seen migrations of middle- and upper-class families from elsewhere in the city. Seemingly overnight, well-regarded schools that had previously served 90 percent or greater populations of minority or low-income students were enrolling ever-growing numbers of white pupils.

Anxiety around that demographic shift, and New York’s status as the most segregated major school system in the country, led to the development of the Diversity in Admissions program. With permission from then-Chancellor Carmen Fariña, principals of seven schools agreed to specifically reserve large percentages of their incoming kindergarten classes for the types of students they worried would gradually be pushed out.

Different schools set different benchmarks. Most sought to attract English language learners or students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, but others set aside spots for students with an incarcerated relative and students in the child welfare system.

The results, at least in the first year, suggest that the program is working. In five schools, including several whose student bodies were becoming woefully misaligned with those of their surrounding neighborhoods, Blom finds that the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch increased. Though she cautions that the sample size under investigation is still quite small — just one incoming kindergarten class in each school — dedicated efforts to increase socioeconomic diversity seem to have made some headway.

At PS 146 Brooklyn New School, where increasing numbers of students commute from the tony neighborhood of Park Slope, more than one-third of kindergartners in 2016-17 were low-income — a jump of 15 percent from the year before. At Manhattan’s Castle Bridge School, children eligible for free or reduced-price lunch increased from 57 percent to 73 percent of incoming kindergartners.

At only two of the schools, Brooklyn Arts and Science Elementary School and the Earth School, did the population of low-income students go down. In an interview, Blom noted that their student populations were already the most likely to come from low-income families of any participating schools, and that the declines were fairly small.

“We’re looking at one kindergarten class, which is very few students,” she said. “So you’re just going to have some natural variation from year to year, and it’s not surprising to me to see that some of them have declined. But I wouldn’t really attribute much meaning to those.”

“Preliminarily, it looks promising to me.”

David Tipson is the father of two children enrolled at the Children’s School in Brooklyn, one of the most coveted schools in the city. He has pushed for the adoption of Diversity in Admissions both as a member of the school community and as the director of NY Appleseed, a group that advocates for integrated schools across the city and state. In an interview with The 74, he said that the program helps parents like him recruit less-advantaged families.

“Parents from our school would go out to a public housing complex and say, ‘Hey, we’ve got this great school, and we’d like you to apply! It’s open to everyone in District 15.’ And they would apply and, of course, not get in — because the applicant pool was completely dominated by affluent, privileged parents. What set-asides allow us to do is to say, ‘You have a realistic chance of getting your kid into this school.’ And that’s a very different ballgame.”

Prior to the program’s implementation, the Children’s School’s population of kids eligible for free or reduced-price lunch was just 10 percent — an incredible 55 percent lower than its surrounding district. In 2017-18, that percentage grew incrementally, to 14 percent. Tipson said that the school would likely shoot higher in its set-aside goals in the future (it currently reserves 33 percent of its slots for low-income students and English language learners).

“Clearly, these percentages are really about calibrating the right amount of boost, and clearly in the Children’s School case, we need some higher percentages.”

In December, the chancellor’s office announced that Diversity in Admissions will be brought to to 42 schools across the city. The expansion is underway as Mayor de Blasio confronts the issue of school segregation in his second term. Earlier this year, he unveiled a plan to introduce more racial diversity at New York’s eight specialized high schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)