Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

If you’re a mid-career teacher thinking about what to do when your career winds down — don’t move.

Seriously, don’t relocate across state lines, K-12 finance experts warn. Along with changing careers, it’s one of the easiest ways to lose out on your retirement savings. In all, only about one out of five teachers receive their full pensions, while roughly 50 percent don’t remain in a single pension system long enough to qualify for minimum benefits at the end of their service.

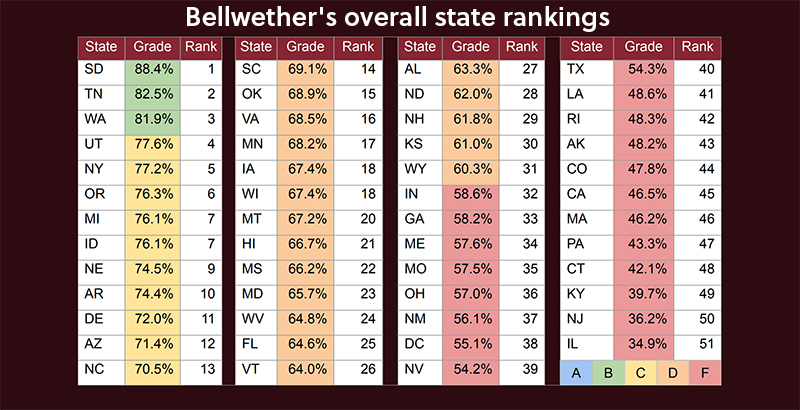

Those dreary findings come from a report on teacher retirement systems released last month by Bellwether Education Partners, a nonprofit research and consulting group. Ranking each state retirement system on an A-F scale, the authors find that only a handful can claim to serve both teachers and taxpayers well: Twenty states received F grades, while none received an A.

Andrew Rotherham, one of Bellwether’s founders and a co-author of the paper, noted that a wide variety of states earned spots near the top and bottom of the list, with both Democratic- and Republican-leaning political environments scattered throughout. But across the board, he observed, the status quo in too many states punishes a wide swathe of educators.

“One of the ways this system is sustainable is that it creates millions of small losers and a much smaller number of big winners,” said Rotherham.

Chad Aldeman, a former Bellwether analyst who now serves as policy director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, said that there had been some “slow movement” in a few states to offer public employees more choice and portability in their retirement benefits, but that the intertwined issues of back-loaded pensions and colossal debts owed by states were generally going in the wrong direction.

“I would say, in broad strokes, the financial problems keep getting worse,” said Aldeman, who worked on a previous version of Bellwether’s rankings and consulted on this publication. “And the related problem about the way the benefits are structured — it’s moving in fits and starts, but it’s also getting worse.”

Bellwether’s newest report evaluates states on a “comprehensive” basis that rates how each system performs for four separate constituencies: short-term teachers (those who teach in the system for less than 10 years), medium-term teachers (those who remain within the system for 10 years but leave before retirement), long-term teachers (those who spend their entire careers in the system), and taxpayers within each state. Retirement systems in all 50 states and the District of Columbia were ranked in terms of their performance for each category, and they all received an overall score.

Grades were determined through the use of 15 separate variables, including overall funding levels, the length of the vesting period, whether teachers in the state are eligible for Social Security, required teacher contribution rates, and investment returns averaged over 10 years.

South Dakota earned the top score, 88.4 percent, while Tennessee and Washington were the only two other states to notch even B grades. Among the lowest-rated jurisdictions were a litany of red, blue, and purple enclaves: California, Texas, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Louisiana, the District of Columbia, and Massachusetts, and more than a dozen others.

Those summative scores can conceal significant variation within systems, however. West Virginia, for instance, earns an overall grade of D, partly because it is one of the worst states in the country for short-term teachers (its 10-year vesting period means that huge numbers of educators won’t stay in the job long enough to earn benefits). But it lands just outside the top ten systems for taxpayers because it participates in Social Security, nets fairly high investment returns, and makes relatively high state contributions.

Among all four constituencies, short-term teachers clearly make out the worst, with 33 states and the District of Columbia earning F grades in the category. Of the rest, only five (South Dakota, Oregon, Washington, Florida, and Michigan) even rated a C or higher.

Aldeman said that the policy moves that have contributed to that reality — lengthening vesting periods, slashing benefits for newer teachers, and raising teacher contributions — can sometimes improve a given state’s budgetary picture, but they also tend to disadvantage younger employees and those who don’t stay their whole careers.

”When states historically have seen a big-budget bill for pension obligations, they have tended to cut benefits for new workers,” he said. “The cuts mean that newly hired workers have to stay longer to qualify for any benefit at all, have to contribute more of their own salary toward the benefits, and have to wait longer to retire and receive a lower benefit.”

Citing a recent report from the right-leaning Illinois Policy Institute, which found that 39 percent of the education funding disbursed by Illinois for the coming school year will be used to pay down the state’s huge debt obligations, Aldeman professed himself “amazed.”

“I mean, you can see the trend; it just keeps going up and up. At some point, will leaders say, ‘That’s enough, we need to do something else about this’?”

‘Life happens’

Teachers in 36 states and the District of Columbia are enrolled in defined benefit pensions programs, through which they make regular contributions to their plan and receive guaranteed payments in retirement. Fourteen states have created “defined contribution” systems, often resembling 401(k) plans, which tend to vest over a shorter period of time and offer greater portability across state lines.

Rotherham argued that education policymakers should not focus exclusively on plan type in debates over how to improve their systems. Defined benefit packages — often caricatured as “gold-plated” vestiges of the mid-20th century, when many employees could expect to retire early with enviable financial security — are not necessarily financially irresponsible for states, he said, and alternative systems can sometimes fail the test of adequacy for the retirees who depend on them.

“This debate has often become very reductionist, and it’s become a debate over what should be the form of the plan — is it defined benefit or defined contribution? — rather than which elements would make it good or bad,” Rotherham said. “And that’s what we need to be talking about because for the plan participants, it’s those elements that affect their lives, not these ideological debates between 401(k)s and pensions.”

Whatever specific structure a state commits to, he said, leaders can no longer condition their retirement benefits on career-long tenures within a given system; any expectation that employees will stay in place for decades is “not a match for our labor market,” Rotherham added.

“If you know you’re going to teach in one place for 30 years, the pension plan works for you, and you should do that. The problem is that people decide they don’t like teaching. They get sick, they have to move, they fall in love with someone whose job requires relocation, they need to be a caregiver. Life happens, people make plans that don’t work out, so these structures have to have some flexibility.”

Disclosure: Andrew Rotherham is co-founder of Bellwether Education Partners and serves on the board of directors of The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)