New ‘Redshirting’ Study Reveals That Boys Are Held Back More Than Girls — and It’s Actually Helping to Close an Achievement Gap Between the Genders

Academic “redshirting” — the practice of holding children back a year before they enter kindergarten — is most widely used by parents of white male students, according to a paper circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Granting certain students that extra year of development before starting school can meaningfully affect achievement gaps, the authors found.

Some parents have always opted to keep their kids at home longer rather than enroll them as the youngest members of a class. But the redshirting phenomenon has only recently waded into the mainstream discussion, most notably after Malcolm Gladwell dedicated a book chapter to the benefits of being the oldest and most physically mature student in a cohort.

It has been estimated by Stanford professor Sean Reardon that between 4 percent and 5.5 percent of students begin school a year late. Research has largely shown that the effects of redshirting on academics are positive, with older students likely to score higher on standardized tests than their younger classmates. One recent study by Northwestern University’s David Figlio indicated that later school entry was associated with higher rates of college attendance and graduation, as well as a lower likelihood of incarceration.

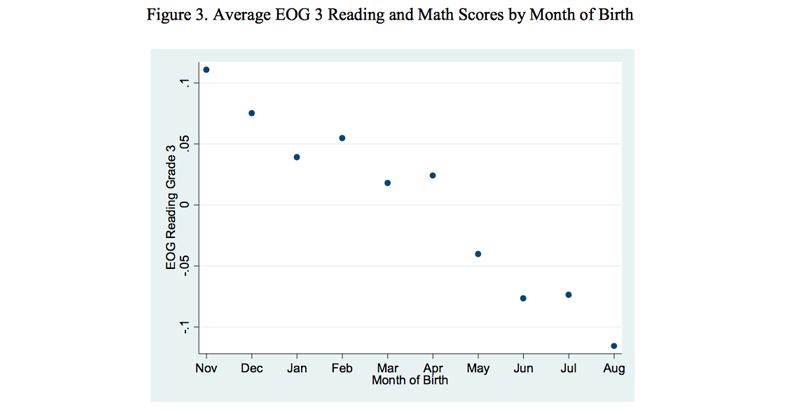

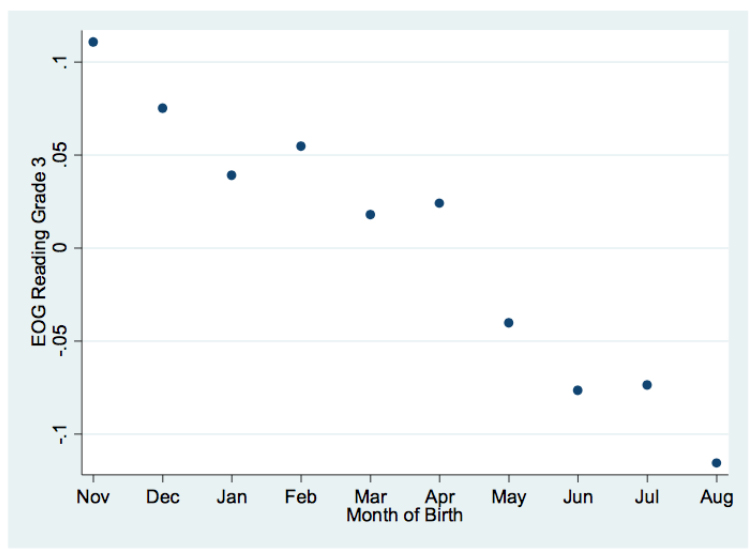

This paper, written by Duke professor Philip Cook, largely replicates those findings. Using data from the North Carolina Education Research Data Center, Cook traced the birth dates, kindergarten entry years, and academic performance of thousands of North Carolina students born between November 2003 and August 2004. Overall, about 6.7 percent of children in the state began school late.

The mean effect of an extra year of age is positive, and striking: Older students were 1.6 percent less likely to be diagnosed as learning disabled, 1 percent less likely to be speech impaired, and 2.3 percent more likely to be classified as intellectually gifted.

Scores for redshirted pupils on academic assessments given at the end of third grade were 0.36 standard deviations higher in reading and 0.3 standard deviations higher in math; Cook notes that both compare favorably to the advantages provided by attending a “no excuses” charter school or learning from an unusually effective teacher.

Cook also identified which students were most likely to be held back before kindergarten entry. White male students were redshirted at the highest rate (9.9 percent), nearly 2.5 times that of black females (4 percent). For white, black, and Hispanic students alike, boys are all held back more often.

That gender disparity produces the important effect of dampening achievement gaps favoring girls over boys. Cook finds that if the third-grade tests controlled for differences in age, the existing difference in scores between white boys and girls would be 11 percent greater. For Hispanic and black students, those gaps would grow by 8 percent and 6 percent, respectively.

The most interesting takeaway, Cook notes, is that “the likelihood of redshirting is strongly inversely related to academic ability.”

“The apparent effect is that redshirting patterns tend to benefit weaker students relative to stronger students,” he writes. “The social value of these effects can be disputed, but without a doubt the concern about boys lagging girls in school is frequently voiced, and an assist for weaker students seems desirable on the face of it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)