New Economics Paper Shows That High School and College Jobs Leads to Higher Wages Later in Life

The growth of the college wage premium — the added financial benefit accruing to employees with a few years of college education, and especially completed degrees — has slowed since the 1980s, according to a new paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research. Additionally, the study’s authors argue that the effects of holding a job while simultaneously enrolled in high school or college are more beneficial than schooling alone.

The study, conducted by economists at Duke, Pepperdine, and the University of Oklahoma, builds on existing research on the impact of education and work experience on wages in the United States over the past 40 years. After a huge spike in comparative earnings for degree holders in the 1980s, their wage advantage has flattened in the decades since, a trend some observers have attributed to improvements in information technology and the decline of “middle-skills jobs.”

To track movement in wages over time, researchers studied three groups of men ages 16 to 29, each drawn from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth put out by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Roughly half the subjects were born between 1957 and 1964, and half between 1980 and 1984. Participants were interviewed regularly on their occupations, education levels, wages, and hours worked to provide a picture of what choices young people made at the beginning of their careers.

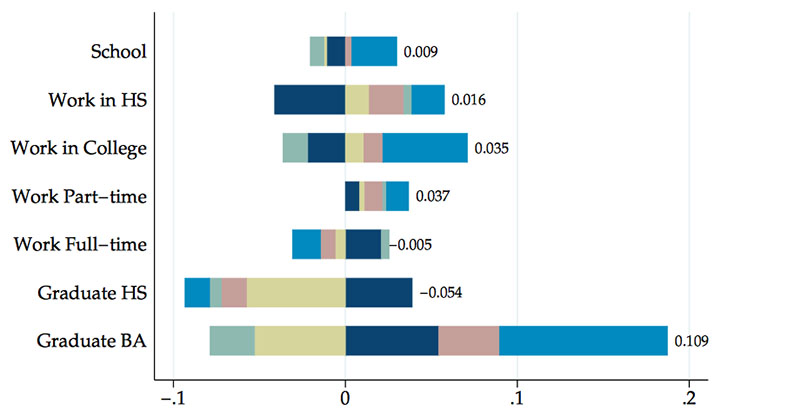

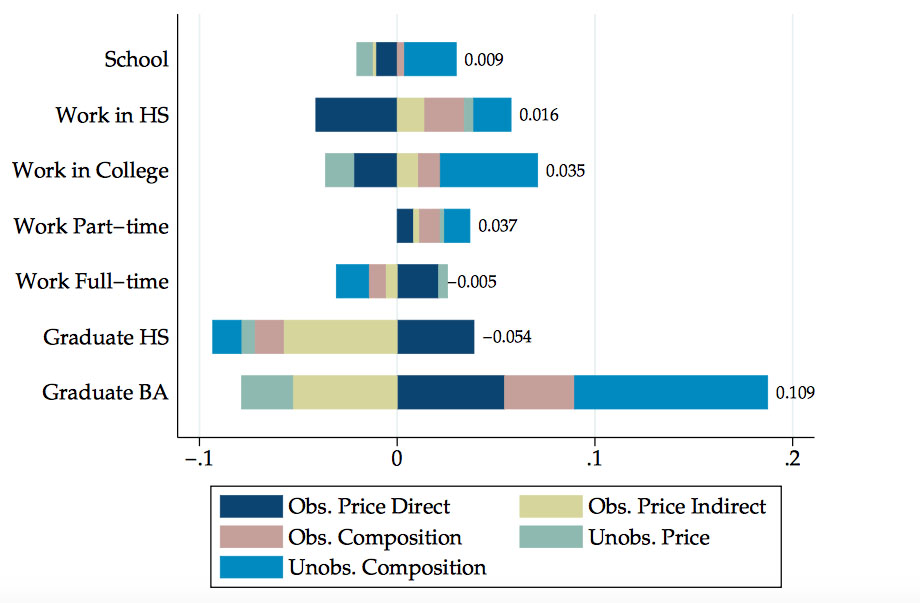

Examination of the data revealed a decline in economic returns from each additional year of schooling, sinking from 5 percent to 1 percent for more recent survey participants. “The returns to a high school degree have increased slightly over this time period, while the returns to a bachelor’s degree have declined since the late 1980s,” the authors write.

In particular, the authors argue, it’s a mistake to attribute college graduates’ higher wages exclusively to their schooling, rather than the work experience they gain while enrolled as scholars.

Although we sometimes picture college students traipsing carefree between classes, football games, and the student union, the vast majority actually take part in the workforce. According to a 2015 report from Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce, over 70 percent of Americans enrolled in colleges and universities work at least part-time, and roughly 40 percent work 30 hours or more each week.

The returns from in-college work range between 4 percent and 6 percent, the authors note, “which are higher than those to any other form of work experience we consider or, for that matter, the return to an extra year of pure schooling.”

College jobs are often related to students’ area of academic focus, which can pay huge dividends after they graduate. A slew of studies confirm that students who complete internships or “cooperative” education programs (often alternating between semesters of work and study) are much more likely to be hired after graduation than their peers who crack the books full time. Even workaday college jobs like barista or busboy stand out to hiring managers, since they require professional attributes like punctuality and teamwork.

While most college students work at least 10 to 15 hours per week, high school students have seen a steady downtick in part-time employment both during school and over summer vacations. Whereas 70 percent of Americans ages 16–19 were either working or seeking work in July 1988, just 43 percent said the same in July 2015. That decline in economic activity has been blamed by economists and lawmakers alike for lost economic activity and wasted human capital.

Compared with holding a job while in college, the benefits associated with high school work are a bit smaller: 3 percent to 5 percent. Notably, however, the return on adolescent labor has increased for more recent students.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)