Listen Up, Candidates: Most Teachers Feel Their Voices Aren’t Being Heard, New Survey Reveals

As the Democratic presidential hopefuls release campaign promises to woo America’s K-12 educators — a key voting bloc — teachers feel left in the dark on major policy conversations, a new survey revealed.

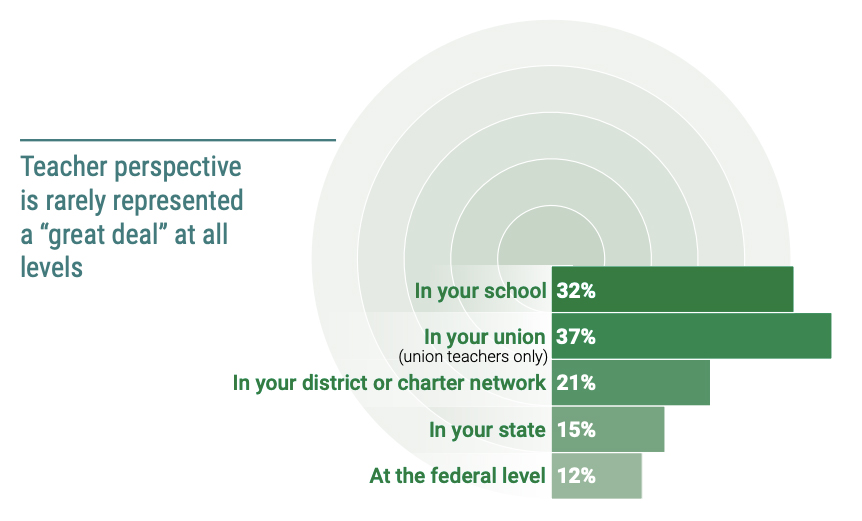

Just a third of educators said their perspectives are considered a “great deal” in teachers union policy decisions, and the numbers fall sharply from there. Only 15 percent of teachers said their voices are sufficiently heard by state policymakers, and 12 percent said the same at the federal level, according to a nationally representative survey released Wednesday by the nonprofit Educators for Excellence.

Similarly, just 48 percent of teachers said school administrators seek their input at least monthly, while fewer than a quarter said the same about state and federal education leaders. Yet nearly all teachers — 95 percent — said they want more opportunities to influence education policy.

The results follow a wave of teacher activism nationally over issues including pay, education funding and school choice. In many cases, teacher walkouts led to tangible policy changes, including increased school funding. The survey touched on a range of high-profile topics that have dominated both teacher activism and the presidential candidates’ talking points.

The upcoming election provides an opportunity for policymakers “to address what is preventing our students from reaching their full potential and us, as teachers, from thriving in our careers,” according to the survey. “We don’t need tweaks; we need meaningful change.”

Teachers likely feel underrepresented in policy conversations because they’re isolated in classrooms as policies evolve around them, Evan Stone, an Educators for Excellence co-founder and co-CEO, said on a call with reporters.

“It’s a challenge that doesn’t have an easy solution but is one the teachers are clearly feeling,” Stone said. But he did point to one potential solution on the local level: Officials could do a better job of including teachers’ perspectives when selecting a curriculum. Currently, just 27 percent of educators say they have a say in curriculum decisions, according to the survey.

To Charles Beavers, an instructional support leader at Chicago Public Schools, inequities in America’s education system have reached a “national inflection point,” he told The 74. In cities across the U.S., teachers have hit the streets to demand equitable opportunities for students, he said, but “this is not a local issue anymore. This is a national issue.” Beavers, an Educators for Excellence member who helped craft the teacher questionnaire, participated in Chicago’s 11-day teacher walkout in October.

But teachers don’t feel particularly optimistic. Nearly three-quarters reported they do not feel valued, and only about half said they are “very likely” to spend their entire careers in the classroom.

The online survey, administered by Gotham Research Group, was conducted in November and included a nationally representative sample of 1,000 full-time public school teachers. Researchers conducted a supplementary survey in December with an additional 500 educators.

In order to bring educators’ voices to the forefront of policy conversations, there needs to be “a concerted, organized effort” on the local and national levels, Beavers said.

“It’s not going to happen just by hoping and wishing,” he said. “Folks have to hit the streets, which we’ve seen people doing over the last four years. We’ve seen folks in the streets, we’ve seen folks advocating for their kids and themselves and for professional respect and fair compensation.”

Issues on teachers’ minds

On the campaign trail, Democratic candidates have elevated teacher salaries as a leading education issue. They’re on the right track, according to the survey. When asked what would keep teachers in their job for the rest of their careers, the answer was simple: better pay.

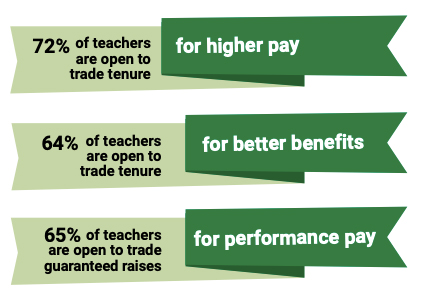

In fact, more than two-thirds of teachers reported they’ve worked a second job to pay their bills. In order to score bigger paychecks, teachers expressed a willingness to make sacrifices. Two-thirds said they’re willing to trade in tenure for better pay or more benefits.

The survey also revealed that teachers are open to merit-based pay, an incentive that’s controversial in policy circles. About two-thirds of teachers said they would consider trading guaranteed small raises for the opportunity to earn significantly more based on their classroom performance. An even larger share — more than three-quarters — support financial incentives for educators who work in high-needs schools, take on leadership roles or teach hard-to-staff subjects like special education.

Teachers’ bottom line is far from the only issue on their minds, however. The survey also touched on several high-profile policy debates, including student safety and school choice.

As school shootings drive heated debates over gun policies and school security, more than a third of educators said they fear for their own physical safety at school at least sometimes. But fights among students — not mass school shootings — were the biggest safety concern among respondents.

School choice, including charter schools and private school vouchers, has become a thorny topic among Democrats, with the leading presidential contenders taking a hard turn away from these options. Teachers are similarly skeptical, the survey revealed. Only about one-third support charter schools or vouchers for students from low-income households. However, there are gradations: 65 percent said they’re open to school choice if it doesn’t shift funding away from public schools, and 55 percent said the same if it improves academic achievement among low-income kids. Just 4 percent of teachers said they oppose all forms of school choice.

For Beavers, teacher recruitment and retention is top of mind. Others seem to agree, according to the survey, with just 12 percent reporting that educator preparation programs train prospective teachers “very well” for the realities of the classroom and 21 percent reporting that the professional development at their school was “very effective” at improving their skills.

“The data show that we need to rethink how we’re recruiting teachers and what we’re doing to make sure that those folks who are qualified and are making a difference day in and day out stay in the classroom,” Beavers said.

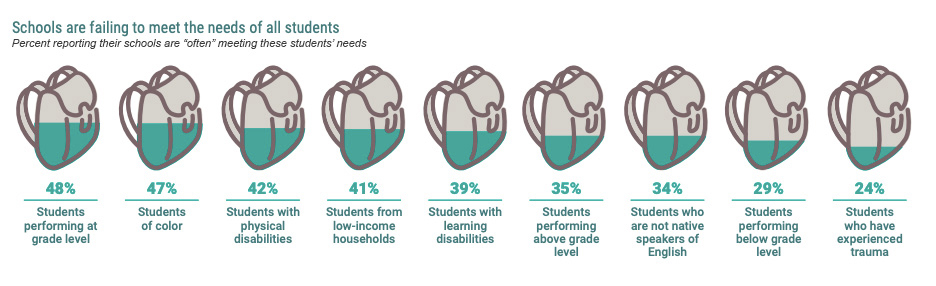

Beyond their own well-being, teachers overwhelmingly said resources are a problem in their schools, which are often unable to meet the needs of many students. Nearly 70 percent reported that school funding is inequitable, while classroom supplies and resources are insufficient in schools that serve high-needs students. Unsurprisingly, early-career teachers and educators of color — who are more likely to work on campuses with scores of low-income children — were more likely to report resource inequities.

While 48 percent of educators said their schools “often” meet the needs of pupils performing at grade level, just 29 percent said the same about children performing below grade level. In one of the bleakest findings, just 24 percent said their schools often meet the needs of students who have experienced trauma. Similarly, only 41 percent of teachers said their schools “often” provide welcoming and inclusive environments for LGBTQ students.

Though the survey revealed that teachers often feel ignored in policy conversations, presidential candidates should focus the bulk of their energy on improving conditions for students, Beavers said. Efforts to create a more equitable education funding model should take center stage.

“The disparities are so huge,” he said. “Even going from schools within one mile from one another, it’s night and day. We’ve really got to put this focus on equity and making sure that all kids get what they need.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)