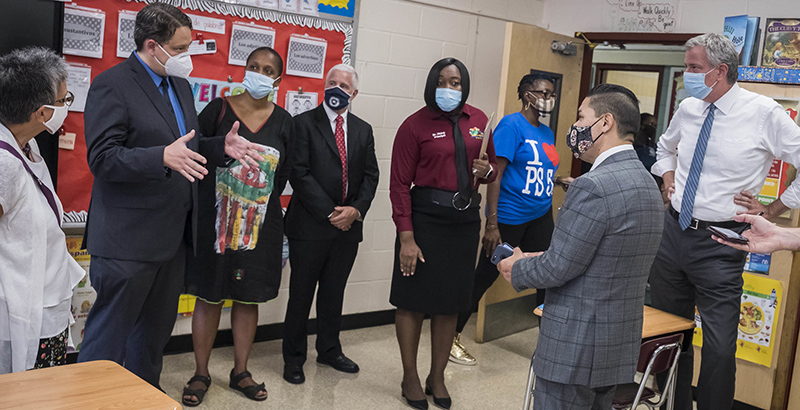

High Anxiety: NYC Elementary School Students Return to School Tuesday Amid Confusion and Distrust

New York City elementary schoolers return to classrooms for the first time in six months on Tuesday, amid a fever pitch of anxiety stemming from rising COVID cases in some neighborhoods, lingering questions over the city finding the staff needed to implement hybrid learning, and a call by the principals union on Sunday for the mayor to hand over his control of schools to the state.

“I don’t think that [the chancellor and the mayor] planned this well at all,” said Marianela Aponte, the PTA president of P.S. 304 in the Bronx. “We’re worried.”

On Sunday night, less than two days before a reopening already marked by confusion and delay, the executive board of the principals union issued a unanimous “no confidence” vote against Mayor Bill de Blasio and schools Chancellor Richard Carranza, saying the state Education Department should seize the reins of the nation’s largest school district.

“All summer long, we’ve been running into roadblock after roadblock, with changing guidance, confusing guidance — often no guidance,” Council of School Supervisors and Administrators President Mark Cannizzaro said on Sunday. “School leaders have lost trust and faith in Mayor de Blasio and Chancellor Carranza to support them in their immense efforts and provide them with the guidance and staffing they need. Quite simply, we believe the City and DOE need help from the State Education Department, and we hope that the mayor soon realizes why this is necessary.”

The CSA was pushed to the brink by a last-minute agreement Friday between the teachers union and the city allowing teachers whose students are learning remotely to work from home, and giving priority for remote assignments to teachers with family members susceptible to complications from the virus. Some 23 percent of the city’s roughly 75,000-member teacher corps have already been granted a medical accommodation to work from home, and the deal further clouded the question of which teachers would be instructing which group of students, and whether there would be enough to cover both in-person and remote learning.

“I’m not confident right now that everyone has the teachers they need,” Cannizzaro said.

“I’m glad [the principals union] had the courage to do this,” said Farah Despeignes, a Bronx parent and Community Education Council leader who helped organize a rally in her neighborhood on Friday night, and who is orchestrating a protest scheduled to take place Tuesday afternoon.

Despeignes said that many parents she’s talking to feel frustrated and unheard by city leadership.

“Generally speaking, parents are feeling it,” she said. “And they want to do something.”

New York City is one of the country’s few large urban districts to attempt a return to in-person learning. Pre-kindergartners and students with significant disabilities went back to school last Monday, while elementary school students returned to buildings on Tuesday. Middle and high schoolers are scheduled to start on Thursday.

Students returning to in-person learning will spend one to three days a week in school and the rest of their time at home learning virtually. As of Friday, 48 percent of the city’s 1.1 million students had opted to forgo returning to school buildings at all — up from 37 percent at the end of August — choosing full-time remote instruction instead.

New York City parent Michelle Proscia said that she decided to keep her children at home this fall months ago, back in April. She has three daughters: 17-year-old Angelina, 14-year-old Maggie and 10-year-old Laura. Years ago, when Angelina wasn’t able to get the one-to-one paraprofessional she needed, Proscia lobbied the Department of Education, and the district placed her daughter in a private special needs school in New Jersey.

Proscia feels lucky to be able to oversee her children’s remote learning during the pandemic. This morning, she was there as they logged into their email and Google Classroom accounts to make sure that they’re ready for the fall. But she worries about parents who don’t have that option.

“What about the essential workers that don’t have a choice, that have to send their kids to school, and then potentially are not being given accurate information?” she said.

Proscia’s statement reflects a growing mistrust among families, officials, administrators and teachers about what they’re being told by the DOE.

Last week, New York City Council issued a subpoena to the department, following up on a request for data on remote learning attendance and access to live instruction that officials first requested in late May.

The mayor has long said that he will shut down the schools if the city’s virus positivity rate exceeds 3 percent over a seven-day average. Although New York has been able to keep its transmission rate low through coordinated efforts at social distancing and mask-wearing, rising case counts in Queens and Brooklyn have some parents worried. The city’s positivity rate hit 1.93 percent Monday, up from 1.5 percent a week before.

“You have a lot of teachers that live in those areas,” Despeignes said of the neighborhoods that have seen increases. “People can just go visit someone over the weekend, and they can bring it back. That has always been a concern.”

New York City schools still face a slew of problems, including a teacher staffing shortage that the principals union estimates at 12,000. Among the criticisms leveled by the union was the contention that city leaders, who have promised an additional 4,500 teachers, pressured some of them to under-report how many teachers their schools still needed.

State Assemblyman Michael Benedetto, a former teacher and Bronx Democrat who chairs the Assembly’s Education Committee, said he’s believed from the start that the city was barreling toward problems with its hybrid reopening plan.

“I have long held the position that the reopening of schools is most likely a mistake on many different levels, and that the only safe thing to do is go to remote learning, at least for the entire semester,” he said.

Of particular concern, he said, are the teacher staffing issues.

“How can you just suddenly get another 10,000 people to fill the void of this?” he said. “I don’t think you can. I offer them lots of luck in trying.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)