Force of Habit: New Study Finds that Routines Could Be Blocking Teacher Improvement

Much education research in the past few decades has pointed to a quietly discouraging finding about teacher quality: After rapidly growing in effectiveness over her first few years in the profession, the average K-12 educator subsequently improves at a much more modest pace. And while that average can obscure significant variation between different teachers, the overall arc of slowing growth has given rise to worries about a “performance plateau.”

A newly published paper by British academics posits an explanation for the phenomenon: the force of habit. Combining insights from research in education, psychology, and neuroscience, the authors argue that as teachers develop a groove in their work, their learning curves level off. In order to combat the “ossification” of practice and stimulate adaptation to new techniques, professional development needs to be geared toward replacing old patterns of behavior with new ones, they write.

The study could influence thinking in the United States, where the push to hone teacher performance has been a hallmark of state and federal education reforms. Its arguments will also provide a new consideration for education leaders grappling with the aftereffects of COVID-19, which has jolted teachers’ routines as much as any development in decades.

Of all the pedagogical and environmental variables in K-12 schooling, teacher quality has been shown to be one of the most significant in determining student achievement. But efforts to assess and improve how instructors work in the classroom, most notably the revolution in teacher evaluation systems during the Obama presidency, have met with mixed results.

Sam Sims, a co-author and lecturer at the University College of London’s Institute of Education, said in an interview that the high cognitive load associated with teaching — not just the transfer of knowledge and skills from teacher to student, but also managing classroom behavior and differentiating among students at vastly different levels of understanding — necessitates the use of what has been dubbed “the double-edged sword of automaticity.”

“On the one hand, we have to automate things in order to build up a sophisticated repertoire of skills,” Sims said. “On the other hand, because of the insensitivity of habits, if new research comes along showing that a certain teaching technique or move isn’t the best way of doing things, this makes it harder to change that in line with what evidence suggests.”

Sims and his collaborators make use of prior research in the fields of neuroscience and psychology to consider K-12 instruction as a habit-building activity. Unlike many other white-collar professions, he said, an abundance of information is available demonstrating whether teachers grow over time, a product of annual testing data.

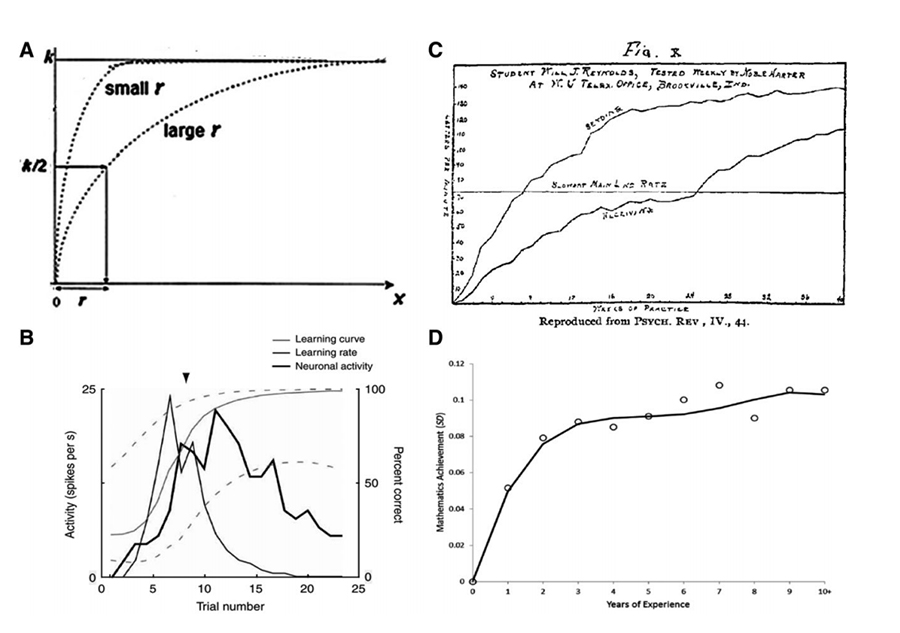

Charted visually, the development of teacher effectiveness on average resembles the improvement of Morse code operators or flight controllers learning to land flights on a simulator: steep improvement in the early phases, as new skills are acquired, followed by a prolonged flattening.

That flattening, the researchers postulate, occurs as more experienced teachers unconsciously transfer cognitive responsibility for a given task to habit-related neurological circuits in their brains. The problem is that when shifting from hyper-attentive skill acquisition to rote memory, they can become insensitive to changes — such as when their instructional habits have stopped yielding growth for their students.

Public schools are frequently asked to implement ambitious new reforms to teacher practices, from the Common Core to implicit bias training; but the nature of the work, often reinforced by the structures overseeing it, can nevertheless push instructors to stick with what they know works. Sarah Woulfin, a professor of education at the University of Connecticut and a former classroom teacher, said that the pedagogical structures imposed by schools and school districts lead teachers to “start working in these really routinized ways.”

“There’s a certain way that teachers do their ‘Do Now’ assignment in the morning,” Woulfin said, referring to the activities that students often complete at the beginning of each lesson. “There’s a certain routine for what you do when students are lining up. How do you collect papers? What do you do when kids are logging onto their Chromebooks? So teachers kind of build up a bank of routines to protect themselves and deal with the number of uncertainties when you have 20 or 25 bodies in the room.”

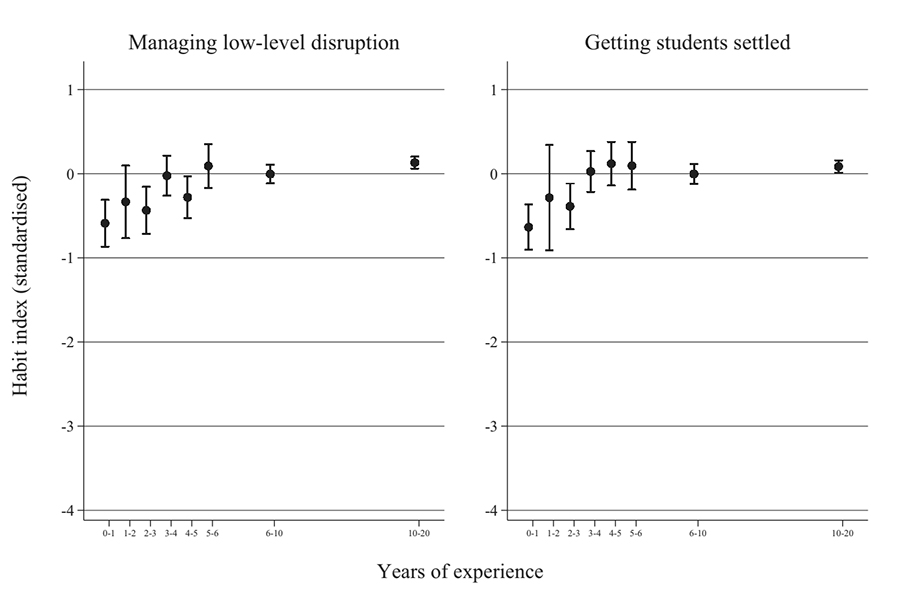

To demonstrate that reality, Sims and his co-authors deployed a questionnaire to over 1,300 instructors in the United Kingdom through the survey app Teacher Tapp. Participants were asked to describe several classroom actions, including getting students settled and dealing with minor behavioral disruptions, according to whether they performed those tasks automatically or had to consciously remember to do so.

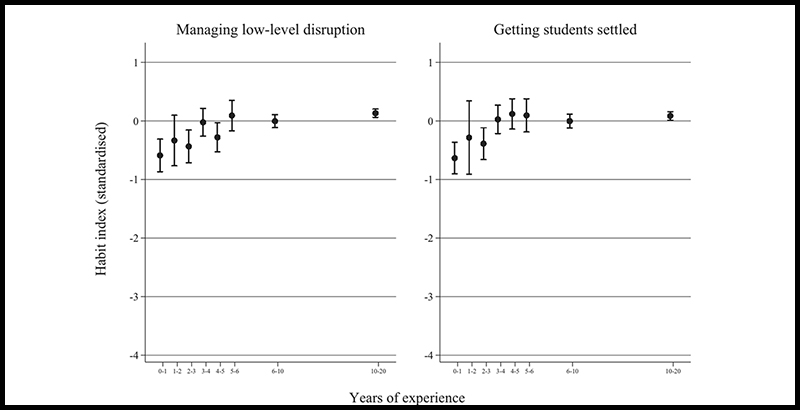

The response data show that teachers at the beginning of their careers displayed much lower rates of automaticity than those with more experience. That rate rose substantially for teachers between their third and fifth years on the job, then stabilized for those between 5-10 and 10-20 years’ experience.

If teacher habit formation is closely correlated with the timeline of teacher improvement, Sims observed, then teacher professional development should be more intentionally designed to break old habits and form new ones that better align with increasing student learning. Standard professional development, which often focuses on making teachers aware of improved techniques — Sims gave the example of encouraging teachers to wait longer after posing a question to students — would be unlikely to succeed unless reinforced by repetition in environments that resemble real-life classrooms.

“Just providing teachers with advice is unlikely to help, because the habitual response [of] ‘Teacher asks the question, teacher gives the answer to the class,’ is always going to be one step ahead of the intention to do it the new way,” he said.

New approaches to instructional coaching held the promise for initiating positive changes. Sims pointed especially to an exercise at the University of Virginia that places pre-service teachers in virtual classrooms, where they were asked to manage student-like avatars that loudly disrupted their teaching.

In fact, the experience of teaching during the remote conditions necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic offers a kind of natural experiment, Woulfin said. With teachers at all levels of experience tasked with adapting on the fly to new schedules and technologies, virtually all were operating like first-year professionals in the initial stages of online learning. While the impact of that rocky transition on students’ academic achievement is still to be measured, polling evidence suggests that teachers themselves feel dramatically less effective than they were before the pandemic’s arrival.

“What we’re doing right now is such a shock to teachers’ work. Is this an opportunity to gain new habits and new routines that could be really beneficial? And what do we need to be aware of if all the old routines no longer work? Teachers have lost those, so how do you thrive under that when so much is new?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)