FAFSA Applications Fell After COVID — And For Many Incoming Freshmen, They Haven’t Recovered

New research from California shows a sizable decline in applications for university financial aid during the first phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. The trend among first-year college students has not reversed itself, the data show, and declines are particularly acute in low-income neighborhoods and those with higher minority populations.

Financial aid applications are a useful proxy for college attendance, which makes it reasonable to wonder whether fewer completed FAFSA forms today will lead to less college attendance tomorrow. Prior research on the FAFSA process has suggested that its complexity may already undermine efforts to enroll more students in post-secondary programs.

The new findings point to developments at the state level that groups like the National College Attainment Network and the National Student Clearinghouse have previously flagged across the country. In the spring, analysts saw a year-over-year decrease of over 350,000 returning students renewing their FAFSA aid. Applications from incoming freshmen dropped steeply at the same time.

But in a brief report published in the journal Educational Researcher, University of Missouri professor Oded Gurantz found that within a few months, aid applications among current undergraduates and graduate students was 8 percent higher than in previous years.

“For older students — we’re talking about older people who maybe have some prior college experience or are thinking of going to graduate school — we see a decline in March, but it actually rebounds over time,” Gurantz said in an interview. “By June and July, there’s actually more people submitting the FAFSA than there are relative to prior years. For traditional freshmen…there’s actually a pretty big overall decline for FAFSA submissions. It goes down and really never recovers.”

The findings depart in some ways from patterns observed during previous times of social and economic uncertainty. Traditionally, contractions in the job market lead more people to pursue education as a means of honing professional skills and waiting out the tough times. During the Great Recession, for instance, America’s two-year colleges experienced a 33 percent increase in enrollment.

But the disruptions imposed by COVID-19 have upended the familiar college experience in ways that administrators and industry leaders have struggled to address. With many two-year and four-year colleges offering virtual coursework and slimmed-down campus amenities, the 2020-21 school year looks like none other in recent memory.

Gurantz and his co-author, Christopher Wielga, compared total FAFSA filings from California between March and August with those from the past three years. Renewal applications rose during that period for sophomores (1.9 percent), juniors (6.9 percent), seniors (11.8 percent), fifth-year undergraduates (17.8 percent), and first-year graduate students (34.1 percent). But among self-identifying freshmen — which can include students who have completed less than one full year of college — applications sank by 7 percent among those with some college experience and a remarkable 21 percent among those with none.

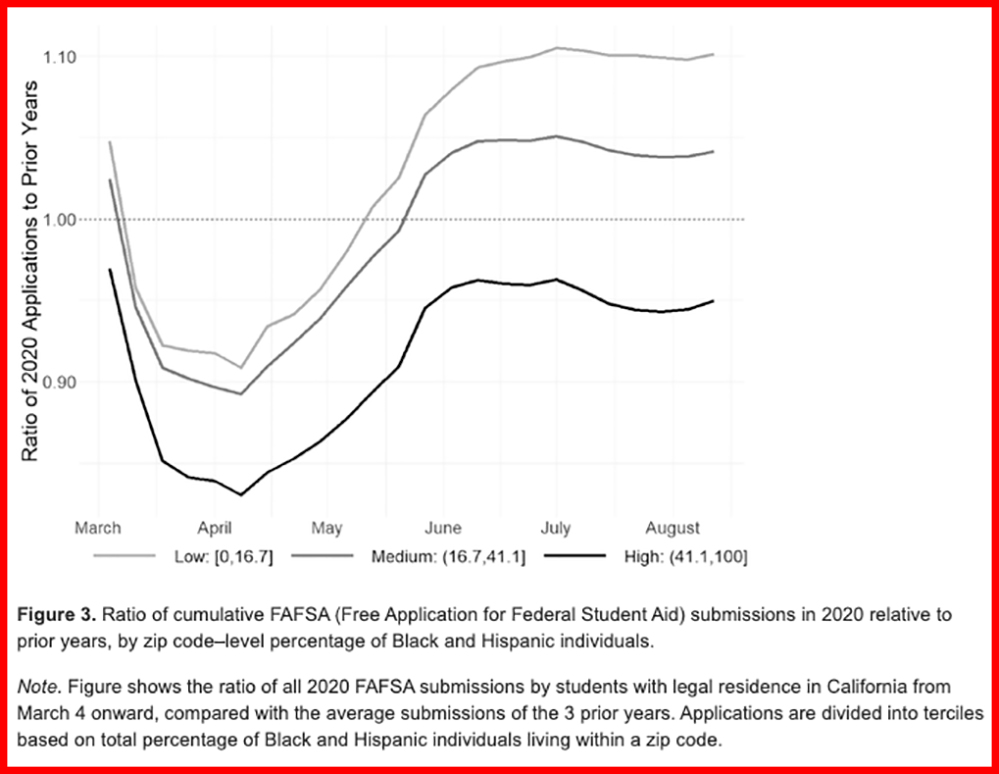

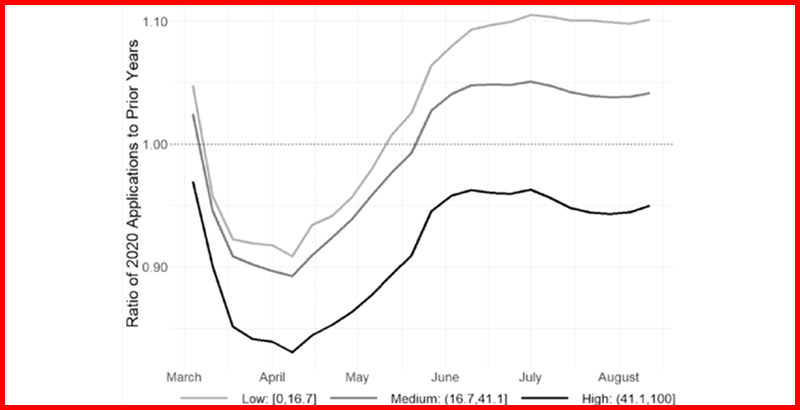

Disconcertingly, outcomes also varied according to background. Linking application information to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s long-running American Community Survey, Gurantz and Wielga found that areas with larger proportions of disadvantaged students were less likely to recover from the initial drop in FAFSA requests. In ZIP codes with the fewest Hispanic and African American residents, applications rose by 10 percent between March and August; in ZIP codes with the highest percentages of such residents, applications fell by 5 percent.

Gurantz noted that younger students may be on especially precarious footing with respect to their future educational prospects. If they miss the transition between high school and college, many will find it hard to reverse course later in life.

“A lot of students who choose not to go in the short term — that ends up being a long-term decision because it’s very hard, once you’re out in the workforce, to go back to college,” he argued. “Freshman year is often when a lot of students, rightly or wrongly, think of themselves as college material or not. When we see dropout rates in college, it’s often the highest after freshman year. You can imagine that this year is a very different kind of college experience, and it’s just going to be much harder for these students to be successful.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)