What the Great Recession Tells Us About the Pandemic Downturn to Come: Expect Declining Student Performance, Widening Achievement Gaps

The sudden appearance and rapid spread of COVID-19 is pushing the American education system to its limits.

As the numbers of new cases and deaths are revised upward daily, the disease overwhelms the capacity of schools to carry out their educational mission. All but three states have shuttered classrooms at least through the end of March, temporarily dispersing at least 55 million students. Teachers are hurriedly adapting their lessons for online instruction, and parents struggle to stay ahead of work while playing part-time tutor. Vital services, which many children access only at school, have been interrupted or abandoned.

But the most serious effects of the pandemic may not have set in yet. If its arrival was an earthquake convulsing our medical and political institutions, the tsunami that follows will be economic. School budgets are stable for the moment, but with businesses closed and millions thrown out of work, state tax revenues will soon come under massive fiscal strain.

It’s impossible to predict how severe the coming recession will be or how long it will take the economy to recover. The U.S. Senate passed a $2 trillion stimulus package Tuesday night, with the House of Representatives expected to give its approval Friday. The bill earmarked $13.5 billion in stabilization funds for K-12 schools, and additional spending bills are reportedly in the offing.

With so much still up in the air, the best guide to the future of schools may be the recent past — specifically, how they coped with the wreckage left by the global financial crisis and subsequent recession of 2008. Although that years-long downturn was different in myriad ways from the present crisis, the enormous damage it inflicted on school budgets could well be repeated in the coming months.

Economists who have spent the past decade surveying that damage say that an economic catastrophe on the order of the Great Recession could seriously hamper both schools and students. Beyond the immediate financial blow absorbed by districts, the reality of pervasive joblessness can lead to family deterioration that is especially destructive to students already struggling to get by.

“There’s a contraction in spending, which means that sales tax — which is one of the largest drivers of state funding for schools — goes down, and job loss occurs,” said Matthew Steinberg, a professor of education policy at George Mason University. “You’ve got these multiple economic shocks: unemployment, reduction in spending, reduction in tax receipts, which means there are fewer resources available for schools.”

Last year, with Pennsylvania State University professor Kenneth Shores, Steinberg published a study finding that the funding cuts imposed on schools by the Great Recession were associated with measurable declines in student math and reading scores. Those declines grew over multiple years, and they were felt most acutely in school districts serving predominantly low-income and minority students.

If the impending coronavirus downturn has a similarly devastating effect on state finances, the resultant cuts to public education could prove just as harmful. But that’s not the only way it might disrupt student learning.

Elizabeth Ananat has also examined the impact of economic slumps on academic performance. A former senior economist for the White House Council of Economic Advisers currently serving as the Mallya Chair in Women and Economics at Barnard College, Ananat has found that widespread job loss negatively affects student mental health, leading to lower test scores. The effects were felt throughout the communities she studied, such that even students whose own parents weren’t laid off saw declines in achievement.

Summary of Education Funding in Senate Stimulus Bill

Whiteboard Advisors

The psychological burden of abrupt economic displacement, from lost work to lost homes, is also borne disproportionately by those at society’s margins. While the depth and duration of each recession varies, Ananat noted with sad certainty that “these traumas have significantly bigger effects on achievement and attainment for disadvantaged kids.”

“I’m hesitant to make too many projections” about the coming downturn, she said. “But I’m not hesitant at all about saying that this is going to negatively affect achievement for kids, particularly kids with any form of disadvantage.”

‘So sudden and so steep’

The features of the coronavirus recession are swiftly coming into view. Unlike the Great Recession, which was underway for months before most people realized what was happening, the economy has effectively slammed on the brakes over the past month.

Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, noted the speed with which contagion-related lockdowns drained the life from travel, leisure and restaurant dining. Just weeks ago, those industries were coasting through a decade-long expansion that some analysts were calling the “best economy ever.”

“I don’t think any other economic downturn has been so sudden and so steep, ever,” she recalled. “Even the last time, the stock market crashed, but most people still did their trips and their conferences, and they went to buy clothes. Sure, they dialed it back, but it took a while for those layoffs to happen. This will all happen over the next few days.”

Woeful indicators seem to trickle in every morning, in fact. On Thursday, Labor Department figures gave the clearest sign yet that unhappy days are here again: The previous week, 3.3 millions Americans filed for unemployment benefits — a 16-fold increase from three weeks prior, and nearly five times the one-week record set in 1982.

Thus far, mass layoffs seem to be concentrated in service industries, which have been battered in the era of social distancing. But with profits sagging and supply chains pinched, the fever will likely spread to the broader economy. One senior Federal Reserve official has projected that unemployment could reach the astonishing height of 30 percent this quarter.

For some sectors, things could get worse. Ananat is currently administering a field survey of hourly workers. Many of those not already fired have seen their regular schedules upended or were forced to stop work and look after their children after schools were closed.

“You’re not talking about 25 percent unemployment for this group; you’re talking about 90 percent unemployment,” she said. “And these are the people who don’t get paid if they don’t work.”

At least initially, this wholesale disruption will most likely injure schools by denying them money. Though some districts primarily use local property taxes for K-12 funding — this is especially true of well-off areas — many others rely on sales taxes collected at the state level. When consumption collapses, so do revenues that support teacher salaries, necessary building repairs and popular extracurricular programs.

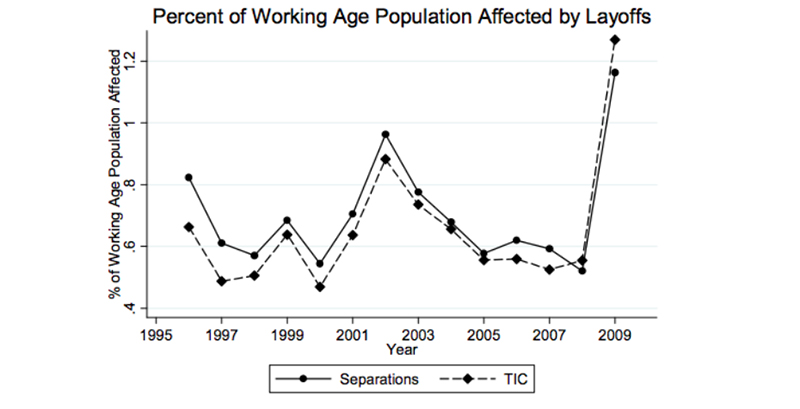

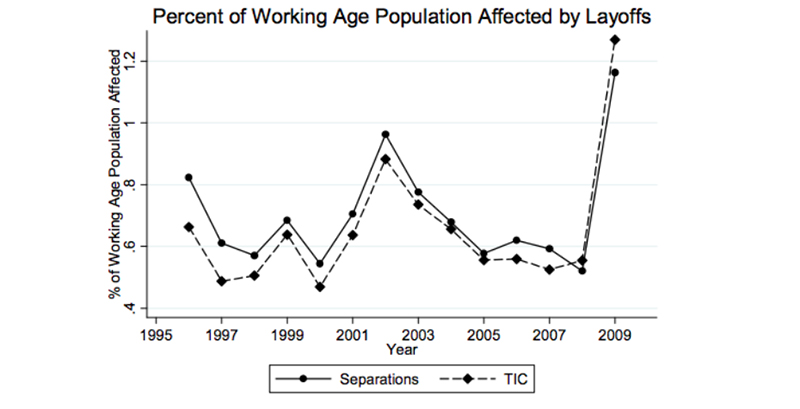

Research shows that state education spending plummeted in the wake of the Great Recession, precipitating a decade of cuts to K-12 programs. But schools in different states and districts absorbed those cuts to varying degrees.

In their analysis of the recession’s impact on learning, Steinberg and Shores derived conclusions by comparing counties that were more or less exposed to financial hardship, as well as students who were enrolled during or after the worst of the downturn. Though the paper didn’t pinpoint a specific causal link between spending cuts and declines in achievement, the two were clearly correlated.

“We saw that achievement went down for kids who were in school during this period and whose spending was cut,” Shores said in an interview.

That finding is consistent with an emerging body of research pointing to the importance of money in K-12 schooling. A 2018 meta-analysis of 64 school finance reforms conducted by researchers Julien Lafortune, Jesse Rothstein and Diane Schanzenbach indicated that increased funding boosted student outcomes in low-income districts.

Shores said that his own work yielded “almost identical effect sizes” between the funding cuts he and Steinberg studied and the funding increases reviewed in the meta-analysis; if sending more cash to financially distressed schools will help them improve, taking it away during economic busts will set them back.

“You give $1,000, [scores] go up a certain amount; you take $1,000 away from kids, they go down an equivalent amount,” he said. “That was the main result from our study — the recession really did have a profound effect on school budgets, and when schools had to cut spending, this resulted in achievement losses.”

With school funding in some states only recently recovered from Great Recession-era cuts, local leaders may be reluctant to enact new austerity measures. But even if budgets don’t substantially shrink over the next year, coast-to-coast school closures are erecting barriers between the nation’s most vulnerable students and critical resources offered at school.

Steinberg said that while he was worried about the damage that a new recession might do to K-12 learning generally, his true concerns lay with poor children now facing gaps in critical assistance. Some, confined to households with little or no internet connectivity, will struggle with the transition to online instruction. But millions more will encounter obstacles of a more elemental variety.

“We’ve got many students in this country who are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch and who are — forget [being] educationally marginalized, their access to food is now at risk,” he said. “That, to me, is hugely problematic. I’m certainly concerned about the educational outcomes, but what we really need to figure out is how we’re going to support the health and well-being of students at this time.”

The widening gap

Ananat says she’s also worried about the fate of America’s neediest students, who start out behind their more affluent classmates. She fears that months spent outside the classroom, only to return to schools offering diminished services, will widen the academic gulf between haves and have-nots.

“I find that, when I’m up in the middle of the night these days, I’m worried about losing ground in educational inequality,” she said.

Ananat’s work has broadly considered the consequences of economic change within communities, often focusing on job loss. Sudden layoffs and business closings, such as those seen during recessions, can exacerbate social ills like homelessness, child poverty and even domestic violence. They can also keep children from realizing their academic potential.

In a 2011 working paper circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Ananat and several co-authors found that states dealing with a one-year job loss to 1 percent of their workers would see an 8 percent increase in the number of their schools failing to meet academic benchmarks set by No Child Left Behind.

The group hypothesized that widespread unemployment took a toll on mental health and family functioning. The extent of the emotional distress was measurable in one grim statistic: Job losses increased by 8 percent the likelihood that a young person would make plans to commit suicide.

Notably, Ananat found that test scores declined even for students whose parents kept their jobs.

“It’s basically stress and trauma and the transmitted stress from other people being stressed,” she said. “We know that adult mental health decreases in recessions even among people who don’t lose their jobs. That’s true for kids also, even when they aren’t directly experiencing family unemployment. They experience increased mental health challenges.”

Added to the perennial difficulties bedeviling families during tough economic times, the novel feature of a nationwide pandemic will pose unique risks to the poor. Given the existing rates of infection, Ananat said, educators could spend much of the 2020-21 school year dealing with children who have lost caregivers to COVID-19.

“More disadvantaged families have much higher pre-existing disease burdens, which means they’re more likely to lose more family members in general, and younger family members,” she said. “So I think kids are going to be directly traumatized by loss, and you’ll have teachers in schools dealing with kids who have been out of school and who have been economically suffering and in grief.”

Asked to conjure a nightmare scenario, Penn State’s Shores said he worried that learning losses related to extended school closures might be compounded by a “second-wave effect” of budget cuts in the fall.

“If, next year, the kids can’t go back to school, and on top of that, school budgets are being cut by 10 or 15 percent, how those schools are going to implement the virtual learning systems when they’ve had to lay off a significant portion of their teacher labor force is a completely unknown quantity. That has never happened before — kids having to work from home, and schools having to deal with massive layoffs at the same time.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)