As Puerto Rico Rebuilds Post-Maria, a Quarter of Its Schools May Close — for Good

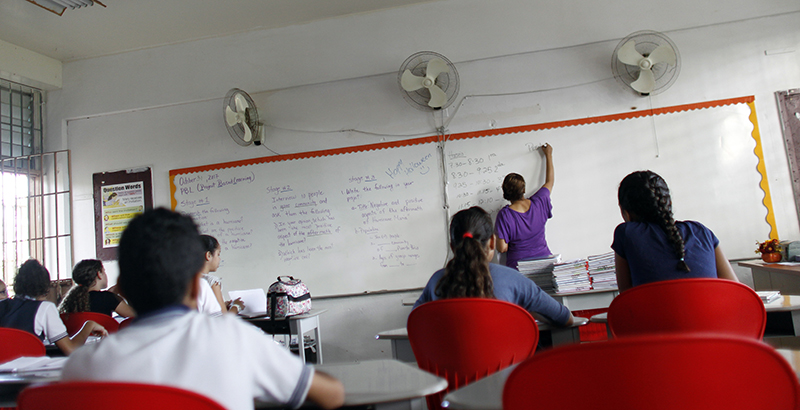

More than four months after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico and shuttered its public education system, almost all of the island’s schools are back up and running, even though many still lack electricity. In the coming months, however, as many as a quarter of Puerto Rico’s public schools could close their doors — this time for good.

On Thursday, Education Secretary Julia Keleher released the timeline for a fiscal plan that would result in the closure of about 300 schools. Currently, Puerto Rico’s education department operates roughly 1,100 campuses. By the end of March, she said, the department will release an analysis outlining 800 schools that should remain open.

“I think the closing of schools is sad and difficult for communities, I do,” Keleher told The 74. “I am sensitive to that, I feel badly for that, [but] I also am trying to stay focused on the opportunity we have, to build a new system of schools that is more on par with other high-quality school systems, and that really prepares our kids to be competitive.”

Puerto Rico Gov. Ricardo Rosselló released the fiscal plan in January. Rosselló announced the looming school closures, which would save the government an estimated $300 million by 2022, as part of a larger strategy to help the island recover from Maria. That storm forced all public schools in Puerto Rico to close for months, many permanently. About 350,000 children attended Puerto Rico schools before the storm; more than 27,000 students have since fled to the U.S. mainland and now attend schools in Florida, New York, and Massachusetts.

Although the school closure plan takes into account enrollment declines that followed the storm — and the thousands more students who are expected to leave in the coming years — Keleher said the strategy runs much deeper. Prior to the hurricane, the government shuttered nearly 200 public schools to rein in spending amid a financial crisis that’s left the island with $123 billion in debt and pension obligations.

Even before the storm, Keleher acknowledged that a swath of additional school closures would be necessary, though the new proposal takes into account an even greater share of students who have left the island. Because so much of the population has departed, motivated by both the financial crisis and the storm, more than 500 Puerto Rican schools are underutilized by up to 75 percent, Keleher said.

“So what I have is a sprinkling of kids in a lot of buildings, but each of those buildings costs me money, and then I have to put teachers in each of those places,” Keleher said. Consolidating schools would save cash, she said, which in turn “leaves me money to buy instructional materials, and we haven’t purchased books in 10 years.”

The closures are also part of a larger reorganization of the island’s education bureaucracy, which Keleher says is stifled by inefficiencies that often leave schools short on resources.

After the storm, Keleher gave educators until January to return to their jobs. Since then, she said, more than 90 percent have returned, though many have since found new positions at schools in mainland communities like Miami and Holyoke, Massachusetts.

Holyoke schools, where three-quarters of the students are of Puerto Rican descent, are currently recruiting bilingual teachers to address the influx of about 200 Puerto Rican students who have arrived since last fall, said Ileana Cintrón, the district’s chief of family and community engagement. Although she said the island’s plan to close schools could benefit their district’s recruitment efforts, she criticized the Puerto Rican government’s plan.

School closures are generally highly controversial, regardless of motivation or circumstance, and the Puerto Rican government’s plan is no exception. In a statement, Aida Díaz, president of the island’s 40,000-member teachers union, the Asociación de Maestros de Puerto Rico, said the plan was unacceptable. School closures, she said, would penalize students who live in rural communities. Closing schools in small towns, she continued, could force families to move elsewhere.

Cintrón, who was born and raised in rural Puerto Rico, had similar concerns, though she said she wasn’t surprised by the latest announcement because the government has been urging closures for years.

“The thing is that some of those kids already travel close to an hour to get to school if they’re in the rural parts of the island,” she said. “Especially high schoolers. I mean, what do you do with that? It’s not always about efficiencies. You want kids to actually graduate and finish high school.”

The closures will rely in part on a per-pupil funding formula that would distribute $6,400 to schools for each student enrolled. The current system has long distributed funds inequitably, Keleher said. But she doesn’t plan to leave rural communities hanging.

“It’s unfortunate that we have to see the closing of schools in communities,” Keleher said, adding that those buildings could be converted into community centers — something that would “still allow that life to be in the community without it having to be such a financial burden to the department.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)