As Chicago Teachers Threaten to Walk Out, New Report Suggests a ‘Hidden Driver’ Behind Rash of Strikes: Skyrocketing Pension and Health Costs

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

If Chicago teachers make good on their plans to strike later this month, it will be the latest in a series of headline-making walkouts launched by educators since 2018.

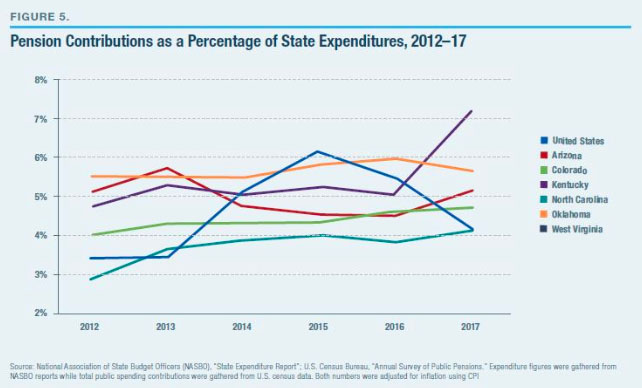

In the spring of that year, teachers swarmed state capitals in West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arizona and North Carolina in protest of their salaries and working conditions. Indeed, teacher pay in several of those states languished in the bottom of national rankings, and per-pupil funding had stagnated or declined in the wake of the Great Recession.

After seeing #RedForEd mobilization win a round of highly publicized battles with Republican legislators, teachers in deep-blue enclaves struck next, demanding higher pay as well as concessions on class sizes and charter schools in cities like Los Angeles, Oakland and Denver.

Chicago is, in some respects, the antecedent to the current activist wave. Though teacher strikes have been uncommon in recent decades, the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) led both a lengthy work stoppage in 2012 and a one-day walkout four years later. The actions were taken in defiance of then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel, whose brusque approach to school reform made him an easy foil for labor leaders. Newly elected Mayor Lori Lightfoot campaigned loudly against her predecessor’s legacy but still finds herself at odds with the CTU, which has announced that it will strike on Oct. 17 if its demands for a new contract are not met. The two sides disagree on how quickly to phase in a salary increase, and other disputes loom around class sizes and staffing.

According to a new report from academic Dan DiSalvo, labor leaders and lawmakers are both missing the most critical factor putting pressure on school district finances: retirement benefits. DiSalvo, a professor of political science at the City College of New York, argues that the mounting burden of pensions and benefits for current and future retirees crowds out other spending. Instead of paying for library books or teacher bonuses, he writes, cities and states devote more resources to pay the health care costs of teachers who have long since retired.

In the report, released this morning by the conservative Manhattan Institute, DiSalvo points to defined benefit retirement plans as “hidden drivers” of both education and teacher strikes. For decades, office holders in states and cities underfunded the plans, confident that the money would be found somewhere down the line. That leaves politicians today to hold the bag as a generation of instructors approach the end of their careers.

It’s a recipe that other experts have pointed to as well. The 74 contributor Chad Aldeman, who studies pension and finance issues for the education consultancy Bellwether Education Partners, has estimated that every active teacher in the United States would see a 7 percent bump in their paychecks if school districts had held their payments to pension plans at 2001 rates. Instead, those payments have gone up, and teacher salaries in many states have stalled as a result.

In an interview with The 74, DiSalvo said that one feature of the problem is the diverging interests of teachers at the beginning and end of their careers. Younger educators — most of whom, Aldeman has written, will not collect their full pensions, thanks to extremely long vesting periods and byzantine eligibility rules — would benefit now from higher salaries, while those closer to retirement are counting on the generous benefits packages they bargained for.

“If you’re a teacher that’s got 20 years in, you’re vested — you’re starting to think about retirement,” he said. “Greater salary might be nice at that point, but you’re probably thinking, ‘I’m dedicated to staying in this state, and I’m going to get my pension and my retiree health plan. That’s my retirement plan.’ It’s very hard to see how you’d get them to change.”

In the meantime, he writes, state spending on teacher pensions and health benefits leaped upwards between 2001 and 2016: From 16 to 23 percent of total instruction compensation in North Carolina; from 15 to 21 percent in Oklahoma; and from 17 to 26 percent in Kentucky. All three states saw teacher strikes in 2018, as school employees grew outraged at their stagnant wages.

At the same time, other outlays have come to encroach on district budgets. One frequently cited expense, not mentioned in DiSalvo’s paper, is special education costs, which have ballooned as states and cities have allocated greater and greater sums to accommodate students with expensive learning needs. In Wisconsin, school districts now spend roughly $1 billion annually to cover special education costs that are not reimbursed by the state. In California, that total was over $10 billion in the 2015-16 school year.

That means that districts like Chicago — which has struggled to get a grip on escalating costs, even as its enrollment has dipped in recent years — have even less money to divide between teacher raises and pension contributions. The negotiations now, he warned, seem to suggest that neither side understands the scope of the problem.

“What’s striking to me is that, just two years ago, there was regular discussion of how CPS needed to declare bankruptcy,” he said. “But now they’re saying, ‘No, we can actually offer a big package of 16 percent raises over five years.’ It just seems wildly optimistic.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)