Wisconsin Reformers Move Toward a First: Education Savings Accounts for Gifted Kids

As a new legislative session begins in Wisconsin, a bipartisan group of lawmakers is soliciting support for a policy that would be the first of its kind in the United States: education savings accounts for gifted students.

The proposal calls for accounts of up to $1,000 to be provided to families of students statewide who are identified as academically gifted — either by their school or by scoring in the top 5 percent on state standardized tests — and are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Although the state currently offers gifted and talented programming in all public schools, high-achieving students from low-income families are less likely to be recognized for their abilities. Money from the accounts could provide access to tutors, extra textbooks, and enrichment opportunities.

The bill, which was introduced in the state Senate last Friday, has a powerful backer in Republican state Sen. Alberta Darling, chairwoman of the Joint Committee on Finance and one of Wisconsin’s most prominent education reformers. She is joined in the Assembly by Rep. Jason Fields, a Milwaukee Democrat who favors school choice.

Outside groups like the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty have given their support as well. In December, the institute issued a brief that warned of a shortage of dedicated gifted instructors and less access to Advanced Placement courses in struggling school districts.

“We know we have a problem with identification of gifted kids, particularly from low-income backgrounds and minority communities, and I think this bill will go a long way to improving that,” said Will Flanders, the group’s research director. “It allows students who are in the top 5 percent on the state exam to qualify for gifted education, which eliminates the possibility for biases in the identification process. These supplemental services are most needed among that segment of the population that is low-income and gifted because those are the kids that have the least opportunity to access the services on their own.”

Economists have recently turned their attention to the high-ability, low-income population. In a 2015 study, researchers Jonathan Wai and Frank Worrell found that just 0.0002 percent of the nearly $50 billion federal education budget funded gifted education. In most districts, children are selected for gifted programming only after being nominated by a parent or teacher; lower-income students, who often lack a dedicated advocate, are frequently left behind.

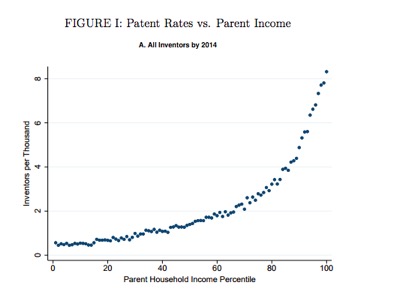

Stanford economist Raj Chetty calls those kids “lost Einsteins.” In a study of patent applications published in December, he found that children from high-income families were 10 times as likely to become inventors as those from families making a below-median income.

Testing data show that the difference in later-life technical accomplishment can’t be attributed to differences in innate ability. The lost potential of countless underserved kids, Chetty concluded, can be measured in squandered technological breakthroughs and economic gains never realized.

Wisconsin is not generally considered a leader in gifted and talented education. A 2015 report from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation gave the state a D for its efforts to identify, track, and educate high-ability students, noting the sizable difference between low-income children and their more affluent peers on international assessments. In the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty brief, Flanders observed that while Hispanics constitute nearly 10 percent of the state’s student population, they make up just 6.5 percent of its gifted classes.

“I would probably agree with the D,” said Scott Peters, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin–Whitewater who specializes in gifted education. “In terms of policy in Wisconsin, there are lots of requirements: All schools are supposed to have gifted education services in grades K-12, and they’re supposed to identify in grades K-12. But those requirements are very weakly enforced.”

For example, a 2011 investigation triggered by parent complaints revealed that Madison Public Schools, the second-largest district in the state, was substantially out of compliance with state law on gifted education. And while all Wisconsin districts in the state are required to name a coordinator for gifted services, nearly two-thirds currently do not.

Peters welcomed the proposal as “a good start,” but opponents see education savings accounts as a Trojan horse for the implementation of private school vouchers, which have proven unpopular with voters. While vouchers give families state funds to pay for private school tuition, ESAs furnish parents with public money to use as they please for educational purposes. To critics, however, that just makes them another means of diverting funds from traditional public schools.

“The authors of the bill are probably well intended, but it’s something that we think is further going down the road of eroding resources for public schools in favor of channeling them to private providers and private school services,” said Dan Rossmiller, director of public relations at the Wisconsin Association of School Boards. “I can’t see any other purpose to the legislation.”

Since Wisconsin’s Department of Public Instruction — led by Superintendent Tony Evers, an avowed foe of Republican Gov. Scott Walker and the current front-runner for the Democratic nomination in this fall’s gubernatorial race — already mandates free gifted programming for public school students, Rossmiller argues that the accounts are almost exclusively directed toward low-income kids already enrolled in private schools through the state’s voucher system.

“This is a law that is not necessarily going to help gifted and talented students who are in public schools,” he said. “It’s a law that, I think, is aimed at low-income students who receive vouchers to attend private schools. … It would create an additional incentive for low-income students to attend those schools, because they would qualify for gifted and talented programming.”

Under the leadership of Walker and his Republican allies in the legislature, that voucher system recently underwent a massive expansion. During budget negotiations last year, the threshold for eligibility for the statewide voucher program was raised to include families earning 220 percent of the federal poverty line, up from 185 percent. Many believe that within a few years, it will rise again to 300 percent, mirroring citywide voucher initiatives in Milwaukee and Racine. Such an expansion would transform what had been an outlay for disadvantaged children into a benefit enjoyed by the middle class as well.

“All you have to do is take out the requirement that it be provided to low-income students, and it’s just a universal program,” said Rossmiller. “This is the nature of how voucher proponents operate: They use the foot in the door, and then they wedge it into a bigger and bigger program by dropping the income restrictions and just expanding programs. I’ve seen this movie before.”

Flanders, who supports both private school vouchers and ESAs, agreed.

“This is a good first step in getting an ESA in place,” he said. “In the long run, we’d like to see them extended to include larger sections of the population, and maybe a universal ESA at some point.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)