Williams: How a Tougher Test and Chaos in D.C. Just Made Things a Whole Lot Harder for Kids Learning English

There’s been public jousting over Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’s approach to civil rights enforcement, sexual assault, and sexual harassment. Members of Congress, state education leaders, and the Trump administration fought over the implementation of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the country’s new K-12 education law. And, finally, congressional Republicans advanced portions of the Trump administration’s proposed budget cuts — especially to teacher training programs — closer to becoming a reality.

Of course, the Trump administration’s now-customary roar of various ongoing scandals (and/or distractions) ensured that none of these relatively prominent education stories broke through into daily news cycles.

In other words, it was a tough time for Corey Mitchell to publish his (fascinating) Education Week story on shifting language expectations for English learners (ELs) in U.S. schools. His article explored the effects of tougher English language proficiency expectations on EL students, as well as on their teachers, schools, districts, and states.

It’s not an easy story for casual education observers to decode, so here’s the basic gist: Most states have chosen one of two assessments to measure their ELs’ English language proficiency. WIDA, which designs and distributes one of these standardized tests, called the ACCESS, recently changed its definition of English proficiency to make it significantly more rigorous. This means that it’s suddenly become more difficult for ELs in these states to demonstrate that they have become proficient — and thereby “exit” the EL subgroup.

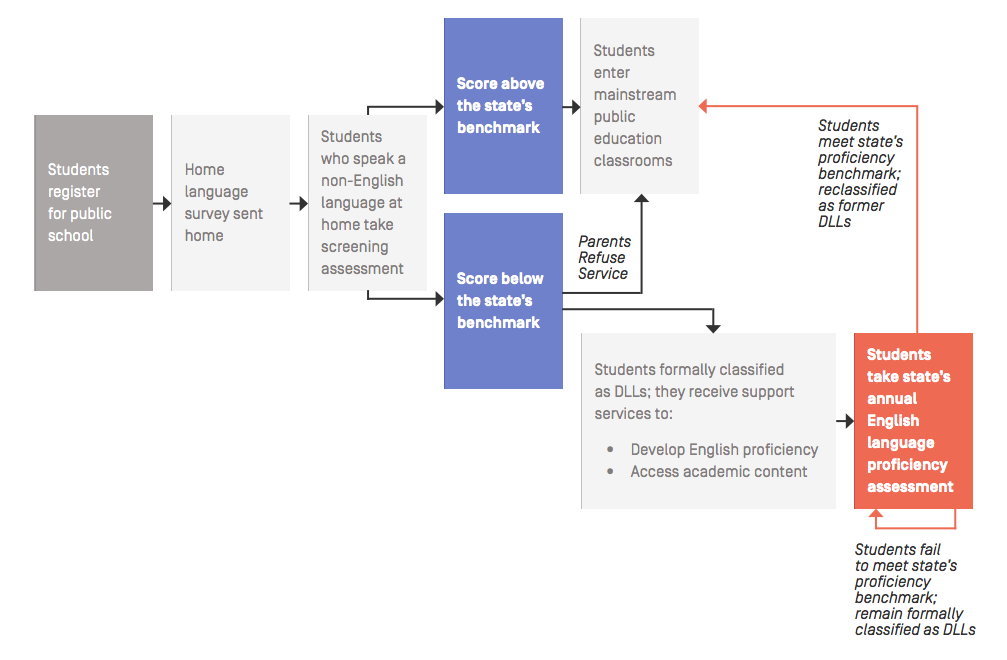

In case you aren’t familiar with the ins and outs of how U.S. schools define which students are ELs — and for how long they’ll stay ELs — here’s a flowchart (which uses the term “DLLs,” or “dual language learners,” instead of “ELs”):

The current shift affects the orange box in the diagram. While states have largely maintained their benchmarks for English proficiency (usually something like “students must score a 5.0 on the WIDA ACCESS test to exit the EL subgroup”), WIDA has changed its calculations to make it more difficult for students to hit these benchmarks. In WIDA’s words, “Students will need to showcase higher language skills in 2016–2017 to achieve the same proficiency level scores.”

WIDA isn’t raising its bar without a reason. “Content standards and assessments now have more rigorous language requirements,” reads a WIDA slide explaining the change. Assessments like the ACCESS are supposed to allow states to determine when ELs’ English skills are strong enough that they no longer interfere with their ability to access academic content in U.S. schools. That is, they’re supposed to determine the point when ELs become former-ELs, when they reach a level of English proficiency that makes them relatively indistinguishable from their peers who were never classified as ELs.

And, see, language proficiency is a relative term; it varies according to the task. This should be intuitive. For instance, I’m sufficiently proficient in Welsh to navigate mealtime and most basic interactions with my wife’s relatives in Ceredigion, but I can’t credibly discuss politics. Similarly, ELs need different types of English proficiency to navigate different academic demands and their social lives at school.

Mitchell describes the sweet spot of English proficiency well: “When moving students out of language-support services … occurs too early, [English learners] can find themselves struggling. If the process happens too late, students may be restricted from taking higher-level courses that would prepare them for college.” So: in a moment of rising academic expectations, is it any wonder that WIDA would adjust its definition of English proficiency to match?

Trouble is, WIDA’s move isn’t a simple matter of aligning an English language proficiency test to new levels of academic rigor. WIDA’s tougher definition of English language proficiency looks likely to keep many thousands of students in the EL subgroup for longer than they — or their schools — anticipated. And this will have significant academic consequences. For instance, in many schools, districts, and states, ELs get language support services that are largely separate from core academic instruction. The longer that these students remain classified as “ELs,” the more academic instruction they may miss.

So here’s the upshot: If new English proficiency expectations look likely to keep ELs in the EL category longer, schools need to think even more intentionally about making sure that these students are set up to succeed. Yes, they need to make sure that students get extra instructional support to help them learn English, but they also need to give these students access to rigorous academic instruction.

Too often, students who are identified as ELs are pulled out of mainstream coursework for English as a Second Language instruction, or are simply treated as if they were somehow academically “deficient” so long as their English skills were still developing.

That is, schools need to recognize ELs’ unique language needs while simultaneously finding ways to better integrate them in mainstream academic instruction. Back in 2015, I interviewed Kelly Devlin, the director of ESL and Equity for the David Douglas School District in Portland, Oregon, on this very issue. She said, “We still have people who push back at both ends. We have former [English as a Second Language] teachers who believe that the only way to teach English learners is to have them isolated in groups of five, learning grammatical forms … We still have classroom teachers who want us to pull them out, sprinkle that magic [English language development] dust on them, fix them, and [think] then I’ll have them in my classroom.”

This view takes a variety of forms, but it’s widespread in American schools. The basic notion is that ELs, as ELs, can’t possibly make academic progress until they reach English proficiency. Although it’s important to be able to accurately identify ELs so that they can get effective language instruction to help them succeed, schools shouldn’t overestimate the distinction between ELs and non-ELs.

Indeed, led by Devlin (and others), schools in David Douglas provide a striking contrast in how they treat their ELs. They offer English language development (ELD) instructional blocks aimed at increasing students’ speaking skills and their academic vocabularies. These ELD blocks connect ELs’ language services with academic instruction and — critically — are taught to groups that integrate ELs and non-ELs.

Meanwhile, schools will be looking over their shoulders as their states begin to implement new EL accountability policies under the Every Student Succeeds Act this fall. The law requires states to track how well schools help ELs advance to full English language proficiency. Many WIDA states will have set proficiency targets based on the old proficiency calculations. Illinois, for example, has said that by 2019, all schools will have at least 68 percent of their ELs on track to reach proficiency after five years of language support.

Although there’s nothing wrong — and everything right — with ambitious goals for ELs, states should be mindful that these goals have now become much more difficult for schools to reach with the more exacting test. In an ideal world, they would be prepared to contribute more resources and think creatively about how to redesign their accountability systems to reflect this sudden shift.

Unfortunately, WIDA’s change won’t just heighten the stakes of schools’ already-difficult balancing act of supporting ELs’ linguistic growth while ensuring that they also have access to rigorous academic content. It also creates new financial challenges. Although the number of children speaking a non-English language at home has increased in recent years, Congress has not significantly increased funding for EL language services.

As WIDA’s higher English proficiency bar makes it harder for ELs to exit, the subgroup’s numbers will swell. Because of a small shift in the definition of “proficiency,” schools will suddenly have more ELs that they are federally mandated to serve — without any significant increases in federal resources to serve them.

And that, sadly, brings us full circle — that is, it brings us back to those aforementioned budget snafus. In theory, Republicans in Washington could get serious about funding ELs’ educational opportunities. In practice, they’re too busy trying to slash the Department of Education’s budget.

And although Mitchell’s story stayed atop Education Week’s “Most Emailed” and “Most Viewed” lists for a few days, it seems like the sort of edu-news almost certain to be lost in the shuffle. One thing, however, is pretty much certain: Amid the bumbling and chicanery that passes for governing in GOP-controlled Washington, D.C., these days, the country’s growing number of ELs aren’t about to get the funding that they need — and deserve.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)