Williams: D.C.’s Vast and Successful Education Reforms Raise the Question: What Next to Close Achievement Gaps?

The businessman visiting from my hometown scrunched up his face in disbelief. Perhaps he hadn’t heard me correctly. Our group was five at a table meant for four in a dark, swanky Dupont Circle restaurant. Servers were shoehorning themselves past like ballpark vendors, shouting out drink specials over the evening’s prandial roar.

“You send your kids to public school here in Washington?”

I did. I still do. But to that conservative Michigan grandfather, this was unthinkable. He was certain that the District was an educational swamp, some awful morass for all right-thinking people of privilege (and especially those of a certain privileged skin color) to flee — and fear.

He’d even opted out of our hometown’s public schools for his children. Surely he’d misunderstood me. Did I mean that I was sending my kids to public schools in a suburb near Washington?

Clearly he didn’t know that D.C. has supplanted New York City as the vanguard of creative, productive thinking about improving schools.

I thought back to that noisy, frustrating conversation while reading David Osborne’s new Reinventing America’s Schools. After a decade in the capital, I thought I more or less knew our schools’ entire recent story. But in Osborne’s section covering D.C. education reform, I discovered that there was so much more to learn. In those four chapters, he points out that, shoot, when it comes to schools, the D.C. education community has tried basically everything.

There are big pre-K–12 governance reforms. Washington, D.C., has slightly over half of its students enrolled in the country’s fastest-improving urban school district, and the remaining 45 percent enrolled in one of the best public charter school sectors in the United States. Both are adding more students each year.

There are heavy investments in early education. The District created its universal pre-K system years before most other cities started building the political coalitions to launch theirs. Not only are 81 percent of 4-year-olds and 70 percent of 3-year-olds enrolled, but D.C. spends an average of almost $17,000 on each child. The city has more kids in public pre-K than the state of Massachusetts.

There is a wholesale rethinking of schools’ approach to human capital. DC Public Schools’ teachers (including those pre-K teachers) are some of the best-paid in the country, and its teacher evaluation system appears to be driving better outcomes for students.

The District’s per-pupil funding is nearly $30,000 per student (which is significantly more than any U.S. state spends). It’s putting hundreds of millions into updating its campuses.

There is ample room to innovate. The city has seen an extraordinary range of school models arise in recent years. There is a Hebrew-immersion public charter school, along with a Spanish-English dual immersion charter school that uses expeditionary learning to deliver an ecologically themed curriculum. There are Montessori district and charter schools, as well as others that use traditional discipline and pedagogy.

There are schools that offer the classical liberal arts curricula, while others offer blended learning models that rely heavily on technology. Many DCPS and charter schools run extended school days and years, and some even offer study-abroad programs. There are schools designed specifically to meet the needs of young men of color, others to help newcomer immigrants succeed, and still others that focus on developing the skills of non-traditional adult students.

There are efforts to weave together school, families, and communities. D.C. has a Promise Neighborhood which, like New York City’s famous Harlem Children’s Zone, offers a comprehensive, mission-driven approach for breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty. And the city’s Briya Public Charter School campuses work with Mary’s Center to offer a “dual-generation” approach to educating children while also helping their families stay healthy, develop their careers, and integrate into American society.

There are ideas, and there are resources to help leaders test them. With its glut of federal education policymakers, think tank jockeys (like me), and education professors, Washington, D.C., almost certainly has the country’s highest education-thinkers-per-capita ratio. Fortunately, the Beltway isn’t just bulging with brainpower (myself excluded) — it can also count on robust local and national philanthropic support for smart new ways to improve its schools.

There’s so much going right in D.C.’s schools.

So I did my best that night in Dupont Circle, shouting back and forth with the Midwestern skeptic amid the clatter. Of course, it was too loud for anything approaching persuasion, let alone a graceful discussion. How do you explain rising scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) while someone just over your shoulder is slowly shouting their way through a list of different glosses on a Sazerac?

And while he was farcically, offensively wrong to preemptively quail at the very mention of public education in D.C., an uncomfortable thought walked me home: If D.C. has tried everything, why doesn’t he know it? Why aren’t the schools doing dramatically better?

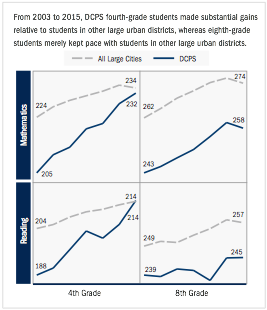

A just-published American Institutes for Research report on DCPS captures the 2017 state of public education. “From 2003 to 2015, DCPS fourth-grade students made substantial gains relative to students in other large urban districts.” This is significant, impressive progress, worthy of attention. However, the report continues, “eighth-grade students merely kept pace with students in other large urban districts.”

D.C. scores are rising. But there’s such a long way to go. Osborne offers a bleak illustration of the problem:

White students in DCPS score higher than whites in any of the 20 other [NAEP] districts. But they also score 55 to 65 points higher than black students in DCPS. Given that 10 points is considered about a year’s worth of learning, that is a huge gap. To put it differently, 75 percent or more of whites in DCPS score “proficient” or above on NAEP, while only 8 to 18 percent of blacks do. The gaps have not narrowed over the past decade.

Given D.C.’s permanently hot housing market, a growing number of privileged families, and a history thoroughly rife with racism, we should worry that the city’s educational progress could have more to do with its changing demographics than with newfound efficacy of its schools. That is, average scores could be up, but those improvements could have more to do with an infusion of gentrifying wealth that is steadily pushing out underserved, underprivileged families.

Indeed, the AIR report found that “Although [math] proficiency rates for Black and Hispanic middle schoolers increased by 3 and 4 percentage points, respectively, between 2015 and 2017, proficiency rates for White middle schoolers increased by 10 percentage points during that same time period.”

What’s left to do? Run down your mental list of what schools need to succeed. Think of the things you tell your friends at the neighborhood barbecue when you talk about how to improve American education. Do you wish we paid teachers better? That we spent more on our schools? That we extended the school day or year to give kids more learning time? That we built a better early education system? That we supported teachers better? That we held them — and their schools — accountable in more meaningful ways? That we gave principals and teachers more autonomy over their work?

D.C.’s pretty much got it all. And we even have the ecosystem to make them work. We have urgency, ideas, resources, capacity, and (at present) relatively tranquil education politics.

Sure, there’s always room for refinement. Perhaps the District should expand its early education work beyond pre-K to support better care for infants and toddlers. Perhaps it should explore different transit models or enrollment patterns across its various schools. Perhaps it needs another round of personnel overhauls like the one inaugurated by controversial, hard-charging leaders like former mayor Adrian Fenty and former DCPS chancellor Michelle Rhee.

Perhaps there are efficiencies to be found that would bring facilities renovation costs down and allow per-pupil spending to crest above $30,000. Perhaps, as Osborne suggests, the city should adjust its policies for assigning school buildings to charter schools to make it easier for high-performing models to replicate.

Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps. But these are relatively smaller moves in a city with so many of the big education policy reforms already in place. And yet, here we are, with high school math proficiency rates 60 points lower for African-American charter school students (8 percent proficient) than their white charter school peers (68 percent).

Surely, part of the District’s difficulties stem from challenges related to child poverty. Ever since the 1966 publication of the Coleman Report, we’ve known that out-of-school factors significantly influence children’s learning in school. Fully six out of every 10 D.C. students qualify for the federal government’s free or reduced-price school lunch program. One in four D.C. children is growing up below the federal poverty line.

Looking beyond the schoolhouse door, progressives might argue that the city could more directly target child poverty through redistribution. Conservatives might encourage local leaders to pressure low-income residents to follow what they call the “success sequence” through school, marriage, and employment. Everyone might look at addressing the District’s bad — and generally worsening — affordable-housing crisis (an inconvenient consequence of that hot housing market).

There’s no right answer, of course. There are countless possible next steps — many of them promising. Seen through one lens, it’s an enviable problem to have: D.C. schools don’t need to try universal pre-K or teacher evaluations or open enrollment policies. They already have them! Seen through another, it’s simply frustrating.

“It’s clearly grown-ups who are the problem here,” said D.C.’s deputy mayor of education, Jennie Niles, at Osborne’s book launch event earlier this month. “It’s not our kids who are the problem.”

Yes. But it’s not entirely clear what D.C. adults should do next. They’ve already tried the proverbial kitchen sink. With any luck, the District’s next stage of education reform might make waves that ripple all the way out to conservative Michigan businessmen … if they can only figure out what to do next.

Disclosure: In addition to proudly sending my pre-kindergartner and first-grader to public school in D.C., I serve as a consultant to D.C.’s Public Charter School Board on English Learners issues (as I’ve noted before).

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)