Williams: Americans Love Simple Solutions, but the ‘English All the Time’ Approach to Teaching ELL Students Doesn’t Actually Seem to Work Very Well

Perhaps nothing defines the United States in 2018 like our deep desire to find that complicated things are actually simple. Our national answer to intertwined, world historical, macro-structural economic phenomena like rapid globalization and automation? Uhh … angry tweets, a wall on the Texas border, and, er, some sabre-rattling about trade wars.

It’s a gift to be simple. Simple is good. Keep it simple — or someone might call you stupid. Say it straight: Nuance is distracting. Details are a pain. It feels good to ignore that stuff. What’s the problem with America? It’s not Great. How do we fix it? We Make It Great. Don’t like it? Shut up, loser.

Of course, anyone who’s survived adolescence, dating, or parenthood knows that variety might be the spice of life … but complexity is its central characteristic. Doesn’t matter how good it feels: Anyone who skimps on the details is cruising for an unintentionally collapsing piece of Ikea furniture, catastrophic drops in projected tax revenue, or a nuclear conflagration. This is the era of the bold, confident man insisting that he knows precisely what he’s doing — right before the grill explodes and sets his house ablaze.

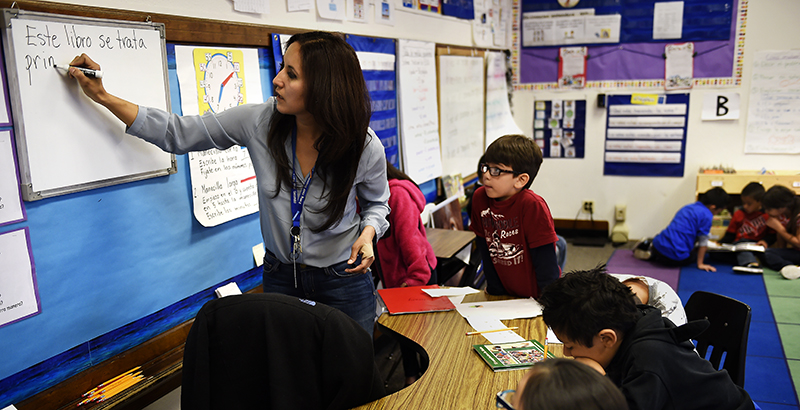

So maybe the world is catching up to education policy, which is wholly rotten with ideas that are intuitive, obvious, clear, and — more or less — fundamentally wrong. Take our approach to English language development. Nearly one-quarter of American children speak a non-English language at home. As their numbers have increased over time, many American schools — and even entire states — have responded with English-only instructional models. These English as a Second Language programs take a variety of forms, but the basic premise is straightforward: The best and fastest way to learn English is to spend as much time as possible with English and as little time as possible with other languages.

Hard to argue with the basic equation. If you’re hungry, you eat more food. If you’re lonely, you seek out more people. If you’re training for a marathon, you prepare by running as much as you possibly can. If you’re trying to teach a young kid a language, you zero in on providing her with as much exposure to that language as possible.

Trouble is, young children’s language acquisition doesn’t actually appear to work quite that way. In study after study, English-only programs don’t generally perform any better than various bilingual education models. The simple “all English, all the time” approach doesn’t seem to work as well as it seems. Why? Well, it appears that, as a 2013 research summary put it, “a learner’s language and literacy in their first language can strengthen their language development in a second language.”

A new study from the American Institutes for Research provides more evidence for this nuanced, less intuitive account of linguistic development. Researchers Brenda Arellano, Feng Liu, Ginger Stoker, and Rachel Slama examined the linguistic and academic trajectories of Spanish-speaking English language learners in New Mexico. They found that students who started kindergarten with strong Spanish skills reached English proficiency faster than students who started with weaker Spanish skills. The stronger Spanish speakers also performed better in math and reading than peers with weaker Spanish skills.

Run that tape back and read it again. Kids’ kindergarten Spanish abilities seemed to be connected to better and faster acquisition of English (measured across four or five years in New Mexico’s bilingual education program).

It’s a small study, and there’s much more to learn from future research on the topic, but the findings are deeply challenging to that simple, intuitive vision of children learning English best by swimming in it nonstop. Indeed, the new research hints that families who speak a non-English language at home may help their children succeed by maintaining and developing that other language.

Which brings us to brass tacks. Much of the English-only movement’s push to keep English-language-learning children out of bilingual education wasn’t really about helping them develop stronger English skills. Rather, the movement often treated language acquisition as a zero-sum game. In this view, families’ usage of another language — Spanish, Vietnamese, Hmong, et al. — implicitly slows their English development and somehow threatens the linguistic and cultural core of the United States.

That’s a pretty straightforward concern. It’s simple, even. And yet, the growing popularity of dual language immersion programs suggests that plenty of American families don’t see languages in such a limited way. Which — why the heck not — is at least a little encouraging. There’s significant research showing that multilingualism helps kids develop a range of cognitive benefits related to focus, attention span, and even conflict resolution skills.

If we survive this current spate of national unforced errors and metaphorical grill explosions, perhaps all these multilingual, multicultural, tolerant, pluralist kids will grow up to lead us confidently into the thorny, complicated mess of a world we’re weaving.

Conor P. Williams is a senior researcher in New America’s Education Policy Program and founder of its Dual Language Learners National Work Group. Williams is a former first-grade teacher who holds a Ph.D. in government from Georgetown University, a master’s in science for teachers from Pace University, and a B.A. in government and Spanish from Bowdoin College. He has two young children and an extremely patient wife. His children attend a D.C. public charter school.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)