Will the Tea Party of 2022 Emerge from the Debate over Schools? Virginia Election Offers GOP Template for Midterms

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

One of the last public opinion surveys conducted before last week’s Virginia governor’s election was released by the Suffolk University Political Research Center on October 26. Its headline results mirrored those of other polls that dropped around that time: Education, usually a political afterthought, had become one of voters’ biggest concerns leading in the final weeks of the campaign. And among respondents who prioritized schools above other policy questions, Democratic candidate Terry McAuliffe was losing badly to Republican Glenn Youngkin, even as likely voters deadlocked overall.

Two weeks later, after a hectic Election Day in which McAuliffe was denied his bid for a second gubernatorial term and New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy barely survived his own brush with an unheralded Republican challenger, the poll’s findings offer one explanation of what went wrong for Democrats in their first electoral test of the Biden era.

David Paleologos, Suffolk’s chief pollster, noted that Democrats have traditionally been the party entrusted by voters to oversee K-12 schools. Healthcare and education have been “the two issue pillars” for the party in the minds of the public, countering Republicans’ traditional edge on taxes and national security. But in Virginia, at least, one of their supports had given way; while 75 percent of healthcare-focused respondents in Suffolk’s poll approved of Joe Biden’s performance as president, just 38 percent of education-focused respondents did.

“There’s a broader potential problem for Democrats when Republican candidates can even be competitive — forget leading — among those primarily concerned with education,” said Paleolgos. “I think that is something that should give Democrats pause.”

The results of the 2021 election cycle will take more than a few weeks to parse, as county-level returns are dissected by number-crunchers in both parties. And the importance of education must also be weighed against structural challenges that couldn’t have been avoided; dating back to the 1970s, the party holding the White House almost never wins the Virginia governorship, while no Democrat has been reelected as New Jersey’s governor under any circumstances.

But two things have become clear in light of the Democrats’ dismal results. The first is that losing their advantage on a signature issue can cost them dearly, even in blue-trending states where they have nominated popular candidates. The second is that both sides now have an incentive to make education a major priority in 2022, when control over the U.S. House, the Senate, and 36 governorships will be at stake.

And the public’s discontent with school systems, ranging from their performance during COVID to their handling of controversial subjects like race and gender, shows no sign of abating. Joanne Weiss, an education consultant who served as chief of staff to Education Secretary Arne Duncan in the Obama White House, said that parents’ fear and anger had first been triggered by the disruptions of the pandemic. But the gradual decline in COVID cases and deaths won’t necessarily bring an end to their outrage, she added.

“COVID response required nimbleness and creativity that the education system was incapable of giving,” Weiss said in an email. “So while COVID was the spark that ignited it, that pile of kindling has been sitting there, unattended, for years. Even if COVID were to magically disappear tomorrow, the smoldering would continue.”

McAulliffe’s political miscue

Virginia Republicans were talking about education throughout their gubernatorial primary and into the general election. But it took a Democrat to bring the issue to national attention.

McAuliffe, a longtime Democratic campaign operative who first served as the state’s governor from 2014 to 2018, infamously said in a September debate that he didn’t believe “parents should be telling schools what they should teach.” The tossed-off remark, made in response to several high-profile cases of Virginia parents objecting to the inclusion of controversial materials in classrooms and school libraries, quickly proved to be the decisive political miscue of 2021.

In a stroke, McAuliffe’s words helped consolidate multiple strands of public disapproval (in a post-election interview with Politico, two senior Youngkin campaign strategists pointed to the moment as “the piece that tied it all together”). Many parents objected to Virginia’s generally deliberate pace of reopening schools to in-person instruction; others — instigated as much by local curricular debates as national messaging campaigns by Fox News and other conservative outlets — sought to ban instruction of race issues that has been grouped under the label of critical race theory. Both were invigorated by the former governor’s apparent dismissal of family concerns.

Stephen Farnsworth, a political scientist at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Va., said that while McAuliffe’s campaign eventually attempted to clarify his meaning, the efforts were “too little, too late.”

“It really became the core of the Youngkin campaign,” Farnsworth said. “The campaign almost entirely morphed into a conversation about parents’ rights in education once McAuliffe made his misstatement.”

Keri Rodrigues, a Massachusetts Democrat and former labor organizer who leads the National Parents Union, said the defeat that followed was proof that Democrats had “taken their legacy as champions of public education for granted.” Though strongly critical of activists attempting to curb the influence of critical race theory, Rodrigues has also pilloried Democrats for their relationships with teacher’s unions (McAuliffe campaigned with American Federation of Teachers president Randi Weingarten during the race’s final days) and argued that the party had failed to hold educational systems accountable during the pandemic.

“We saw the catastrophic failure of our nation’s public education system happen in our living rooms, and we were left to fend for ourselves,” Rodrigues said in an email. “Since that point, Democrats have outright rejected any criticism of the performance of these systems or recovery efforts — while parents and families have continued to be left struggling with their concerns unheard.”

Democrats running in both state-level and congressional races next year will benefit from the example of McAuliffe’s gaffe, and Farnsworth theorized that they could avoid similar missteps by calling for school governance to be led by a “partnership” between parents and education professionals. Moreover, the party will still have the opportunity to pass a host of family- and school-related initiatives through its Build Back Better legislation, including universal preschool, paid family leave, and a permanent expansion of the Child Tax Credit. Given a year to advertise those achievements and watch COVID’s threat to public health slowly diminish, Democrats could once again seize the initiative on a policy area they have historically dominated.

According to polling data provided by Gallup, Inc., the public has trusted Democrats more on education almost continuously for the last three decades. Election-year polls from 1992, 1996, 2000, 2008, and 2016 all found respondents favoring Democratic presidential candidates to manage schools, usually by double-digit margins. (Then-president George W. Bush took a late lead on the issue in his 2004 contest with John Kerry, and no data could be found for the 2012 presidential election at the time of publication.)

But Paleologos said that Democrats’ failure in Virginia had already consigned next year’s crop of candidates to answering press questions about whether parents should have input in how schools are run. Pointing to past Republican successes with pre-election platforms like 1994’s Contract with America, he predicted the GOP would seek to use education as a wedge to split liberal Democrats from the center.

“Even if you pass some really progressive education legislation, Republican candidates are going to force Democrats to” make some commitment to parental control over K-12 schools, Paleologos said. “Now, a smart Democratic candidate would say, ‘Yeah, I’ll sign a Contract with Parents,’ but then they’re going to be at odds with their progressive base.”

Push for a ‘red wave’

Youngkin’s victory served as a proof of concept for the notion that a deft Republican could win votes by crafting his closing argument around schools. But it also cast doubt on Democrats’ own campaign strategy of tying opponents to Donald Trump at every opportunity.

Paleologos observed that the first-time candidate’s template — one that could be exported next year to battleground states like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Maine, where Democratic governors will be running for reelection — was to win back middle-class voters in the suburbs while “one-upping Trump in rural areas, even without having Trump next to him.” It’s unknown how much Trump, who has supercharged Republican turnout in two national races, intends to campaign with GOP hopefuls next year, and recent polling suggests that he remains a deeply divisive figure. But Youngkin enjoyed a surge in downstate support even in Trump’s absence, riding the former president’s endorsement to nearly half a million more votes than the Republican gubernatorial nominee received in 2017.

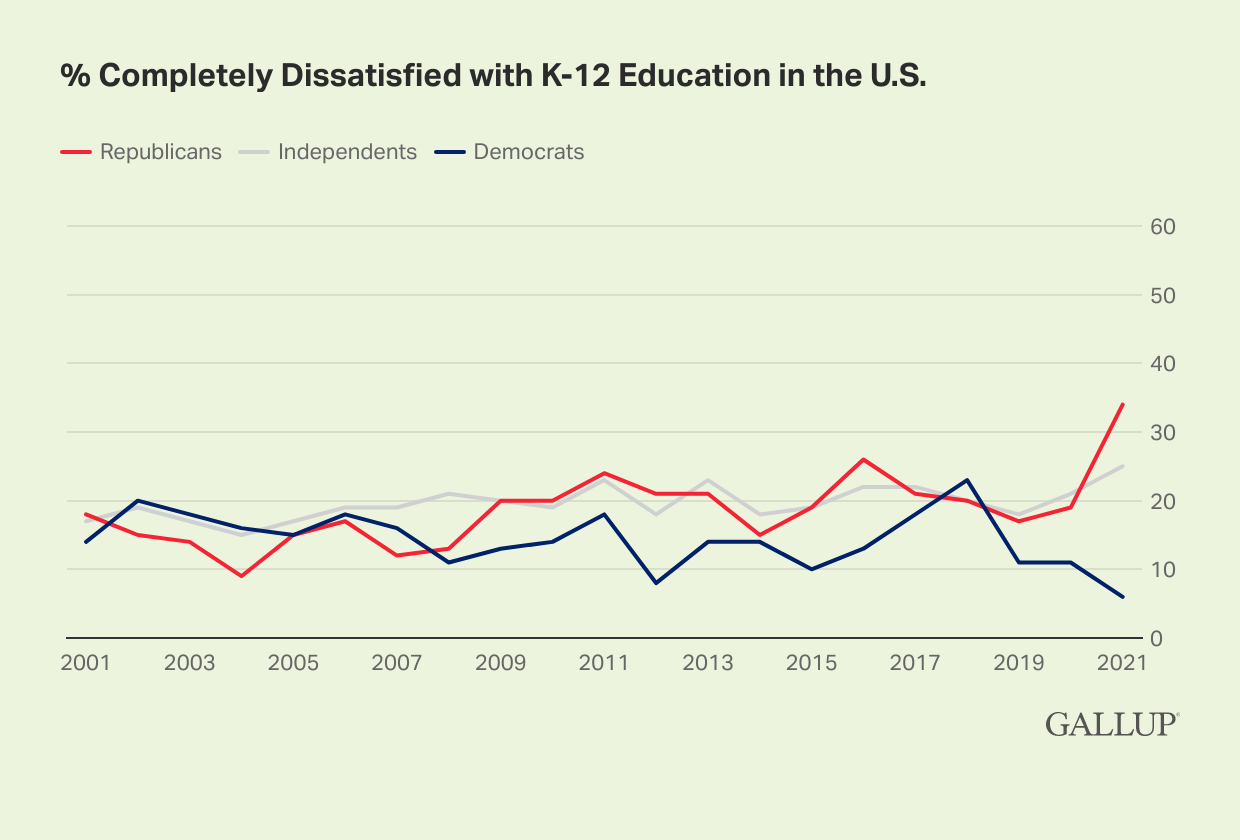

Republicans’ hopes for a red wave will rest on the enthusiasm of their base, which has shown itself to be extremely animated by K-12 issues. A Gallup poll released in August found that 73 percent of American parents were either somewhat or completely satisfied with the quality of their children’s education, roughly in line with previous years. But a detailed breakdown of the results provided by the organization found that 34 percent of Republicans described themselves as “completely dissatisfied” with schools, by far the highest level for that group since 2001. Twenty-five percent of independents said the same, representing a seven-point jump since before the pandemic began.

If the stage is set for a national push, the party seems ready to make one. In the immediate aftermath of last week’s elections, at the same time Democrats took steps to finalize the framework of their Build Back Better legislation, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy announced that Republicans would soon introduce a “parents’ bill of rights” to promote transparency in curricular content and protect the participation of parents in school governance.

The question is whether such initiatives are the stuff that majorities are made on. The last midterm wave favoring Republicans came in 2010, when right-wing activists incensed over deficits, government spending, and Obamacare coalesced in an amorphous movement known as the Tea Party. A revival of that feat will require coordination and skilled messaging, Farnsworth said, but education could offer a useful conduit for conservative energies that exist already.

“In many ways, the critical race theory debate of 2021 is just the latest version of the death panel conversation from Obamacare, or the Willie Horton story of 1988. The question isn’t whether this is an accurate portrayal of what’s going on, the question is whether this can be weaponized to benefit Republicans. In 2021, as in 2010, as in 1988, the answer is yes.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)