Why These Two Tulsa Educators Returned Home to Save the Latino Students Too Often Left Behind

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Walking past wire fences threaded with weeds and weaving her way in between large pickup trucks parked in driveways, she peers over a gate and waves at family members standing on a front porch.

“Hi! Are you Emily’s parent?” Ducey asks.

The dad descends the stairs warily. “Yeah. How do you know?”

Ducey, armed with a list of every fourth-grader in Tulsa Public Schools, tells Emily’s dad about a new 5-8 charter school, a free college prep middle school that just opened in their neighborhood in 2015. Would he be interested in sending his daughter to Tulsa Honor Academy for fifth grade?

The dad takes an envelope with an enrollment packet in both English and Spanish from Ducey, agreeing to take a look.

Tulsa Honor Academy, which teaches three hours of literacy and two hours of math each day and has a strict code of conduct, is trying to level the playing field for children whose lives and educations are literally precarious. When a tornado touched down here not long ago, families were forced to flee the trailer park to seek shelter in a local church. It was the night before the state tests, Ducey said.

Sitting for the exams the next morning on little sleep was yet another challenge for the kids from East Tulsa —many of them immigrants and English-language learners whose families struggle to make ends meet.

The Hispanic population in this heartland city of roughly 400,000 people in northeastern Oklahoma is growing fast. Three years ago, Hispanic students became the majority in Tulsa Public School classrooms, at 31 percent. Blacks and whites follow, each accounting for some 25 percent of the student body, while the rest are mostly students who are mixed-race and Native American.

Math teacher Sasha Ducey speaks Spanish with a parent in an East Tulsa neighborhood as part of a canvassing effort for the school she teaches at: Tulsa Honor Academy.

Driving home that evening on Highway 169, Ducey pulls out her red sunglasses to block the glare of the setting sun and gestures emphatically with her hands.

“We just saw the neighborhoods that we went to — those are poor neighborhoods, but those are the students that I teach, and they’re quite capable of doing anything that they put their mind to,” she said. “But a lot of them haven’t been given the chance or even laid out [those] expectations.”

Raising expectations for students too often dismissed is what drew Ducey’s boss, Elsie Urueta, back to her hometown to open Tulsa Honor Academy. The school serves 206 students, almost all of them Latino and 98 percent of them qualifying to receive free or reduced-price lunch. Urueta, 31, dressed in brown knee-high boots and a blazer, stood before Ducey and 19 other adult volunteers earlier that Sunday getting ready to go out and canvass for 2017’s fifth-graders.

“We kind of profile in the sense that we take a map of East Tulsa and we go to the neediest areas, even within East Tulsa, and we start there, so we start with the trailer homes and we start with the apartment complexes, and we look into the rest of the neighborhoods,” she said, holding up a map. “We want to make sure we’re serving the students of highest needs because a lot of times those are the students that don’t have access to a lot of opportunities.”

The daughter of Mexican immigrants, Urueta returned to the 42,000-student Tulsa Public School system that is run by Deborah Gist, who was also raised here and also came back in 2015, determined to make a difference after a career in education that brought her national attention.

These two Tulsa educators grew up in the classrooms they’re now fighting to save from budget cuts and teacher shortages.

Teacher pay in Oklahoma is among the worst in the country — 49th out of 51 states (including D.C.) — and voters crushingly defeated a November ballot measure that would have given teachers a $5,000 raise this year.

All education funding is hurting in Oklahoma, where dropping oil prices have crippled budgets in this energy-dependent state. Since 2008, per-pupil funding has been cut 27 percent here, more than any other state, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. One third of the state’s 1,803 public schools now operate on a four-day-a-week schedule.

“I think teachers were just sick and tired of being disrespected and sick and tired of education being treated so shabbily,” said Karen Gaddis, who is Gist’s former teacher and one of 26 educators so incensed by the situation they ran for office in 2016. (Only five were elected.) “You can’t make changes just standing on the sidelines.”

Urueta and Gist do not intend to. If not full-on partners, they also do not see themselves as rivals across a district-charter divide that has grown wider and more bitter in many cities.

“The public charter schools that are authorized by our Board of Education, we consider them to be a part of the Tulsa Public Schools family,” said Gist, who has visited Urueta’s school and provides facilities support to the charters in her district.

Linda Brown, who runs the Boston-based Building Excellent Schools, a group that offers intensive fellowships for school leaders interested in creating high-performing charter schools, has worked with them both.

(The 74: Meet Linda Brown, the Grandmother of America’s Best Charter Schools)

“Deborah does not stand up and shout. Elsie does not stand up and shout,” Brown said. “Their shouting is soft and effective. Their shouting is dedication, commitment and persistence … I think that both of them want to see change in their own time. They’re not in the business to make things better 75 years from now.”

At 7:28 a.m., a walkie-talkie beeps.

“It’s 7:28,” a crackling voice says.

The voice belongs to Urueta. And the teachers who hear it know what the message means. It’s time to take their places inside the school. Feet move. Papers shuffle. Doors open.

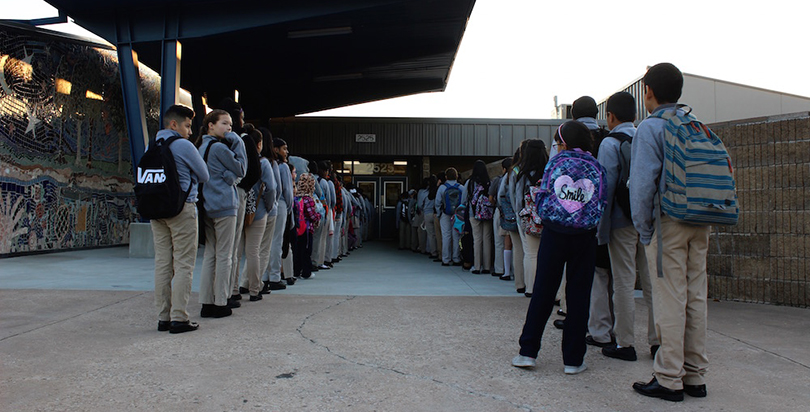

Office manager Gus Ibarra walks through the school’s blue front doors, where two lines of students are perfectly filed in gray quarter-zip sweatshirts and backpacks. He slowly makes his way down the middle, hands outstretched like a football coach, collecting high fives from all his players.

Office Manager Gus Ibarra greets every student with a high five or handshake before the school day starts at Tulsa Honor Academy.

In the parking lot, he serves as the school’s official greeter, opening every car door with a “Good morning” or a “Buenos dias” to the parents and students inside. He shakes the students’ hands or gives them a high five before they line up.

For the students who don’t ride the bus, Ibarra is their first point of contact before sitting down in the classroom. And he’s a familiar face not just for students, but also for their parents. Ibarra spent his early childhood in California but for the past 16 years has lived in Oklahoma. He knows many of the Tulsa Honor Academy families personally.

“I went to high school with her uncle,” he says after one car drives away. He opens another door and smiles. “And they take care of my goddaughter,” he says.

The students’ second touch base is Urueta, whose official title is lead founder and head of school. She welcomes every one with a handshake and a uniform check. Students lift their pant legs and sweatshirts to show Urueta they are wearing plain black or white socks and a black belt. They must be wearing khaki pants and a gray polo shirt. It’s perhaps the strictest rule at Tulsa Honor Academy, which offers uniform scholarships to families who can’t afford them. Still, if a student has so much as a Nike swoosh on their socks, they can’t go to class and must wait in the office until someone brings them socks without a logo.

“Have a great day, hon — high five,” Urueta says as a student passes the check and walks through the door.

The third and final interaction with an adult before school starts is with the classroom teacher. Students line up outside their classroom, where their teacher also shakes their hand and quizzes them on something they’ve been learning, in this case units of measurement. Once they answer, students grab a white bag on a tray with their breakfast — an apple, a milk carton, juice and a muffin — and make their way to their seats.

These three early-morning conversations are meant to teach students how to interact and speak professionally to adults: shake hands, make eye contact, speak clearly. It’s also meant to make the middle schoolers feel seen and known by their teachers and school leaders.

Tulsa Honor Academy’s firm code of conduct would fall into the “no excuses” model favored by some charter schools. One of the first signs a scholar sees as she enters the school building is a large white poster with some of these rules: “Walk on the tape all the way to your destination. Do not cut corners. Remain silent.” The tape is thick and purple and runs along the floor with arrows pointing in different directions through the hallways and classrooms.

Elsie Urueta checks student uniforms every morning before school.

The model is not without its critics. Some argue that it continues to oppress the low-income students whom many charter schools serve with rules that aren’t always present outside of school. Others say students aren’t given the preparation to think for themselves, unlike their wealthier white peers.

Urueta explains the system with an analogy: It’s like driving on a road. People don’t feel secure if the lines dividing the highway are faded or missing.

“[Students] don’t see it as oppressive, because they see it as a structure that supports them, and that’s what it’s meant to do,” Urueta said.

If the school’s 85 percent retention rate in its second year is any indication, parents agree. Gabriela Yllescas said she “loves” the rules because it teaches her daughters about manners and not just academics. Parent Rigo Mireles said the rules prepare students for higher education, life and a serious work ethic.

Rigo’s 11-year-old son Yadier also sees the benefits.

“I think it helps me stay more focused to remind myself that I’m supposed to be doing this or that,” he said.

Parent Rigo Mireles chose to send his son Yadier to Tulsa Honor Academy because he hoped it would provide a more challenging academic environment for his son.

Parents expressed hope that the code of conduct and commitment to academics could help keep their kids out of trouble outside of school, away from drugs or dropping out. There has been dramatic improvement in the national dropout rate for Hispanic youth — going from 32 percent in 2000 to 10.6 percent in 2014 — but it remains higher than for both black students, at 7 percent, and white students, at 5 percent.

To promote a college-going culture, the teachers at Tulsa Honor Academy tout their universities, christening their classrooms after their alma mater. They familiarize their students with the college’s name and story and give them a team to cheer on during sporting seasons. In the hallways, pennants from seemingly every college hang on the wall between the lockers and the ceiling.

The days are longer at this school. Students arrive at 7:30 a.m. and leave at 4:30 p.m. Rather than recess, students get 15-minute breaks every two hours, which most use to chat with their peers, draw or play games. Students stay in the same classroom all day; it’s the teachers who rotate, to maximize learning time.

Yadier and his parents are seeing the results of this intensive instruction. In one year, he got straight A’s except for one B. He also received a science award from his teachers, loves social studies and has taken a liking to a new engineering class offered this year.

“In the beginning, we built rafts and then bridges, which we’re testing,” Yadier said. “It’s fun.”

On the latest state test, 77 percent of Tulsa Honor Academy students scored proficient in math and 60 percent in reading. That compares to 52 percent proficient in math and 62 percent in reading for Tulsa Public School students.

Eventually, Urueta said, the school has plans to relax the rules as students get older and have learned from them. But for now, the results are immediately obvious. Students are silent in the hallways and the classrooms. Well, most of the time. Every morning, for a few moments, they get really loud.

“Who wants to lead the chant today?” a teacher asks her class. The teacher shares the room with Ducey, who spent her Sunday recruiting and who graduated from Villanova.

“This is my favorite part,” Urueta whispers.

A small girl with a big white polka-dot bow in her hair raises her hand from the back of the classroom. She slowly gets up, grips the back of her chair and stands on her tippy toes.

“Villanova!” she yells, in a voice that fills the room.

“Wildcats!” the class yells back.

“Villanova!” she screams again.

“Wildcats!”

Beautiful, exciting, cutting-edge. Those are some of the words Deborah Gist uses to describe Tulsa. Oh, and home.

“Tulsans are people who will do anything for their neighbor and who deeply care about public education,” Gist said.

That may be, but Oklahoma teachers right now are not feeling the love. Their poor pay has had real consequences for students and administrators like Gist trying to keep their districts fully staffed. As the 2016 school year began, more than 500 teaching jobs in Oklahoma remained unfilled. That’s after 1,530 jobs were eliminated the prior school year, according to the Oklahoma State School Boards Association.

(The 74: Why Oklahoma Is Racing to Put Nearly 1,000 Uncertified Teachers in Its Classrooms)

“I think what I learned, or came to understand better once I was here, was how badly our teachers are compensated and the effect that has on them,” said Gist, who was able to begin her school year with no teaching vacancies but was still disappointed when the salary measure was defeated at the polls.

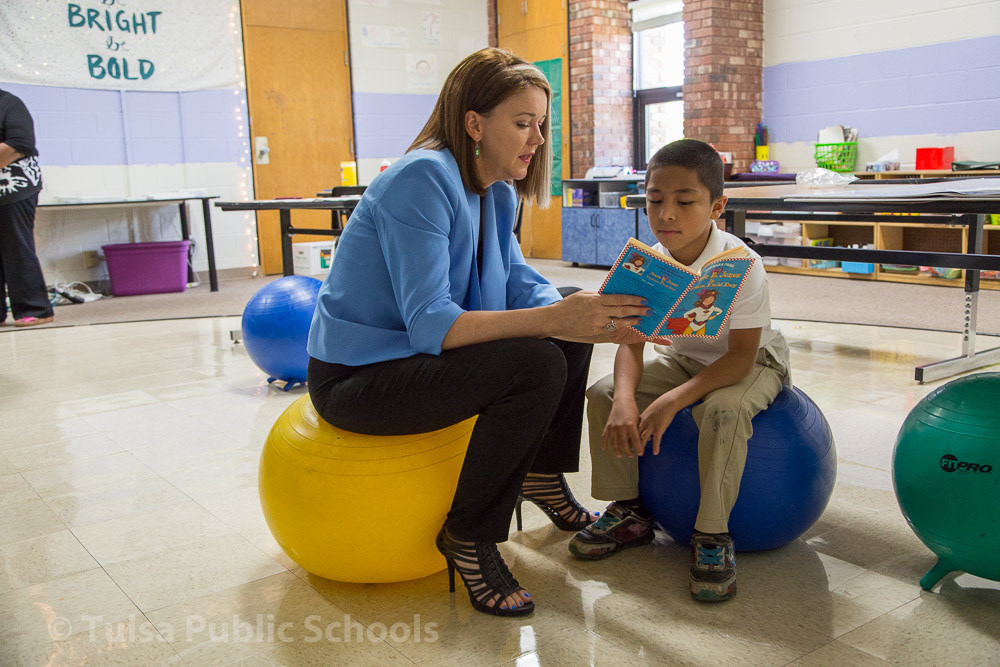

Tulsa Public Schools Superintendent Deborah Gist reads to a student.

Teachers are being lost to states like Texas, Arkansas and Kansas, according to a state school board association report. Texas can pay teachers 16 percent more than Oklahoma can. The starting salary for a first-year Oklahoma teacher is $31,600. In Tulsa, it’s $32,900. Even after 20 years in the classroom, a Tulsa teacher with a bachelor’s degree earns $44,430, or $46,736 if they have a master’s degree. In Urueta’s school, teachers make 20 percent more than district teachers but also have a longer workday. Urueta’s salary is $85,000.

(The 74: Oklahoma’s Teacher of the Year Makes Just $35,419 — and He Won’t Get a Big Raise Anytime Soon)

Gist said she’s heard a lot of feedback about teachers feeling that the district was not concerned about them or not supporting them. In the 2015–16 school year, only 34 percent of educators agreed that the district showed concern for their school’s needs, according to district data.

“We have had to do some real hard work here in the district office to confront that and to say we are an organization that exists only to serve our teachers and schools,” Gist said.

Some of that came directly from Gist, who earns $235,000 a year and receives an end-of-year performance bonus. In May, she donated that $25,000 to the Foundation for Tulsa Public Schools, given what she called “the indefensible salaries we provide teachers in Oklahoma right now.”

Facing a limited budget, Gist, who says said she’s always been a believer in maximizing resources, has found other ways to support her teachers. The district has raised private money to fund professional development on classroom management. It also reorganized how the district assists schools on social and emotional learning by creating network teams of psychologists, social workers and behavior specialists that are assigned to one set of schools so principals always knows whom to call when they need help.

Tulsa Public Schools Superintendent Deborah Gist has been passionate about education since she was a student.

Gist, 50, remains strongly connected to her own teaching roots. In her district office stacked with books and festooned with whimsical memorabilia, she keeps a project on her desk that she completed in junior high, when she and her classmates had to chart their careers. Hers was preschool teacher, and she interviewed her own preschool teacher for the assignment.

Now that she is back home, she keeps in touch with her old teachers, including Gaddis, her high school algebra teacher, who ran for the Oklahoma House of Representatives. Gist credits Gaddis with giving her the necessary enthusiasm and skills to blaze through her graduate school math.

And Gaddis, who has about 30,000 students to keep track of from nearly 40 years in the classroom, has been proud of Gist’s work so far.

“She has such a big heart for children, for education,” she said. “She’s going to be highly successful in her career.”

One could argue she already is. Gist has served as a senior policy analyst for the U.S. Department of Education, as the state education officer for Washington, D.C., and as Rhode Island’s education commissioner.

In 2010, she was named among Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People in the World” and one of The Atlantic’s Brave Thinkers for her work in Rhode Island, which included raising test-score requirements for teacher training and establishing annual teacher reviews. At that time, she also approved the firing of all the teachers in the very low-performing Central Falls school district, a sweeping step supported by President Obama and then–U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan. The controversial action also brought Gist much criticism from the public and the teachers union.

Before all that, Gist was an elementary school teacher in Texas, after studying early education at the University of Oklahoma. She also worked in a Florida school district designing a literacy curriculum. In addition to her undergraduate degree, she holds master’s degrees from both the University of South Florida and Harvard University and a doctoral degree in education leadership from the University of Pennsylvania.

Even as Gist traveled the U.S. exploring education, she kept her eye on Tulsa. When the former superintendent announced his intent to step down, several people from Oklahoma quickly contacted her, Gist said.

This was near the same time the Rhode Island Board of Education allowed the deadline for renewing Gist’s contract to pass without taking action. It had been 30 years away from home, but this felt like the right time to return, she said.

Brown, founder of Boston’s Building Excellent Schools, was shocked when she first learned of Gist’s decision to move back to Tulsa. But she ultimately understood.

“I think it’s the same draw Elsie had,” Brown said. “Family.”

When Urueta’s mom, Elsi Flores Walkabout, first heard her daughter wanted to start a school, she was hesitant.

“Oh my God, now what? You told me you were going to be a lawyer,” Walkabout recalls, laughing. Now Walkabout is Tulsa Honor Academy’s biggest recruiter, attending canvassing events, conversing with parents in Spanish and pulling families with young children aside after Sunday Mass at St. Thomas More Catholic Church in East Tulsa.

Her daughter and namesake was born in Texas, but the family lived on both sides of the border between Juárez, Mexico, and El Paso, Texas. The Uruetas moved 11 times before settling down in East Tulsa.

“My mom always told me that I had to work — because I was an immigrant, a Latina woman — that I had to work twice as hard to be able to reach my goals,” Urueta said. “She told me this from a very young age. So when opportunities were given to me, I always took them. But the problem is so many of our kids don’t even get those opportunities to begin with.”

Elsie Urueta stands outside Tulsa Honor Academy, the middle school she founded several years ago to encourage her East Tulsa neighborhood of immigrants and English-language learners to attend college.

One of those chances came in the person of Donneva Bennett, Urueta’s second-grade teacher. Urueta smiles at the memory of the woman who took time at recess and after school to sit with her and teach her English. That kind of focused attention, Urueta said, put her on track to earn good grades and take advanced classes.

Not every student struggling with English has a Ms. Bennett. By the time she was in AP courses in high school, Urueta observed she was one of only a few Latino students in the room. She attended the University of Oklahoma but was troubled by the thought of all her friends and neighbors left behind.

Of the 18-to-24-year-olds living within Tulsa Honor Academy’s ZIP code, only 2.5 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher, while 27 percent of those 25 and older have a college degree, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. By comparison, 37.7 percent of Tulsa City residents 25 and older have college degrees.

So as a freshman at the University of Oklahoma, Urueta began translating financial aid information into Spanish for local high schools in Tulsa and Oklahoma City.

“And through my work there, I very quickly realized this was a systemic problem,” Urueta said. “It was more than just language and cultural.”

After graduation, Urueta joined Teach for America, where she worked in charter schools in Chicago and St. Louis. There, she had a conversation with a student that changed the way she thought about her dream of starting her own school. A sixth-grade boy was explaining to Urueta the appeal of local gangs: the chance to acquire reputation and honor, he said.

“And I remember saying, ‘No, what brings you honor is an education, and what brings you honor is ensuring that you go to college so that you can get a better quality of life and better support your family,’ ” Urueta said. “That’s what honor is.”

From that moment, Urueta knew her school would have the word “honor” in its name.

Urueta’s fellowship at Building Excellent Schools was critical to her making that school real. The program accepts two out of every 100 applicants, and potential fellows must show local support for their proposed school by submitting signatures and letters of recommendations. Most, Linda Brown said, collect 200 to 300 signatures and 15 letters; Urueta gathered 2,500 signatures and 30 letters, more than any other applicant since the program began in 2003.

“Elsie competes with the best, and most of the times she wins,” Brown said. “That’s what she wants for her children and the school.”

Parent Gabriela Yllescas was one of the first to sign on to the new school, enrolling her oldest, Gabriel, in Tulsa Honor Academy’s inaugural fifth-grade class. Yllescas wanted more academic rigor for her daughters. She didn’t like when they came home without homework. At first, Gabriel didn’t want to go. She didn’t like the sound of the strict rules or having to leave her friends. But Yllescas insisted that with the school’s higher expectations, Gabriel would perform better.

Yllescas said she wants her daughters to graduate from college and have the educational opportunity she couldn’t as one of eight children growing up in Mexico. Her husband, who works in an auto-body shop, tells his daughters that he doesn’t want them to have to work as hard as he does.

College banners decorate the hallways and classrooms of Tulsa Honor Academy. The middle school’s mission is to prepare every student for college.

Gabriel is in sixth grade this year, and while she tells her mom she won’t admit to “really liking it,” she said she’s getting used to it and making friends. Her sister, Michelle, is a fifth-grader at Tulsa Honor Academy, and Yllescas said she loves it.

“Sometimes they talk to me, my kids, they talk to me about ‘When I’m in college,’ and I like it when they talk like that,” Yllescas said. “They do it because they told them in school.”

At Tulsa Honor Academy, 85 percent of students are Latino and 10 percent are African American. Of the Latino students, 67 percent speak Spanish at home and 16 percent are English-language learners.

The Every Student Succeeds Act, the new K-12 education law that replaced No Child Left Behind, places increased emphasis and accountability on the progress of English-language learners. It abolishes the Title III category, which previously tracked ELLs, and places their English proficiency into Title I, which provides educational oversight of other vulnerable learners, such as special education and low-income students. The test scores of ELL students will be excluded from state results for the students’ first school year in the U.S., used only as a measure of student growth in their second year, and included in the state’s overall results in their third year, according to the Oklahoma Policy Institute.

In November, the Oklahoma State Department of Education released a draft of its new ESSA accountability plan. The state is considering setting five years as the goal for English-language proficiency for ELL students, depending on their English skills when they enter school. ESSA also requires states to intervene in their lowest-performing districts. Oklahoma plans on keeping its A–F school-grading system, but it will have to revise it to include English-language proficiency and to fully take into account high school graduation rates.

Oklahoma picked chronic absenteeism as the nonacademic measure it will use in determining school quality. In Oklahoma, chronic absenteeism is defined as missing 18 or more days of school. In Tulsa Public Schools, poorer students are more frequently absent, and Native Americans are more chronically absent than other racial groups, Gist told the school board at a November meeting. The findings were part of a larger report on racial and economic disparities facing the district. On state tests, 80 percent of black students and 70 percent of Hispanic students are performing at the lowest level in math, compared with 50 percent of white students. In reading, 35 percent to 40 percent of black and Hispanic students perform at the lowest level, compared with 20 percent of white students.

Gist and Urueta face those gaps every day as they pursue similar educational missions at different scales — Gist running a sprawling district with ever-shrinking funds while inspiring talented teachers back into the classroom; Urueta pushing all of her students, despite cultural expectations, to graduate college during the four years she has them.

“We as a school focus so much on closing the academic achievement gap, but we know we’re not ignorant,” Urueta said. “We know this academic achievement gap is a result of an opportunity gap.”

The Walton Family Foundation provides funding to The 74 and to Building Excellent Schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)