Oklahoma’s Teacher of the Year Makes Just $35,419 — and He Won’t Get a Big Raise Anytime Soon

He also recently ran for the state senate this year as an independent (he lost) and was one of the earliest supporters of an initiative to raise Oklahoma’s sales tax in order to increase teacher pay.

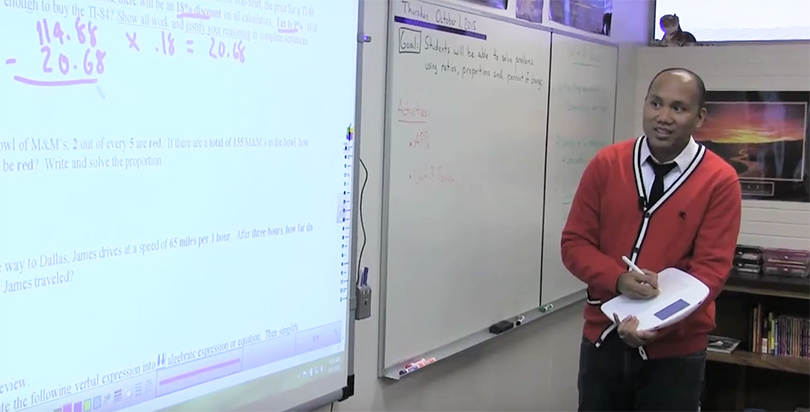

And his annual salary as a high school math teacher is $35,419; counting benefits, it’s just over $38,000. His monthly take-home pay is just $2,047.

That’s because Oklahoma teachers are some of the worst-paid in the country.

Yet the ballot initiative — which would have increased the sales tax by one percentage point and given teachers a $5,000 raise — was overwhelmingly defeated. Sheehan and his colleagues will not get a raise.

“We’re not poverty-stricken,” Sheehan said. “But it’s a challenge for sure.”

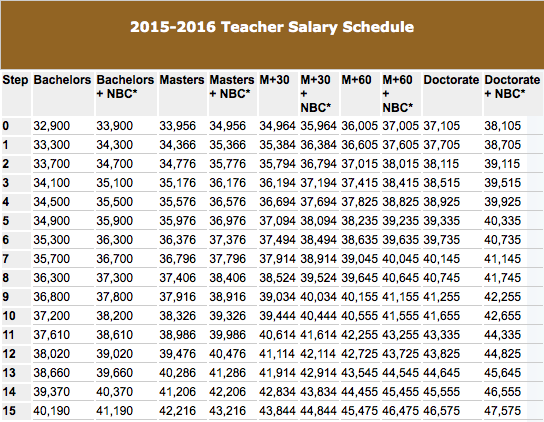

Teacher pay across Oklahoma is remarkably low. The average starting salary in the state is just over $31,000, among the lowest in the country. A Tulsa teacher with a master’s degree and 13 years’ experience still makes under $40,000; a teacher with a doctorate, National Board Certification, and 33 years’ experience makes just less than $60,000.

Teachers can move to any of the states surrounding Oklahoma and expect a significant pay raise — and many do just that.

“We could go three hours south [and] the starting [salary] of Fort Worth [teachers] is like $51 [thousand] and change,” said Sheehan, who works in the city of Norman.

There is a long-running academic debate as to whether teacher compensation is “over” or “under” that of similarly educated professionals in other fields. A recent analysis by the Economic Policy Institute found that teachers make about 11 percent less in total compensation than similar workers putting in comparable hours elsewhere. Another study found that high school teachers earned less than other professionals, but elementary and middle school teachers made more.

These sorts of comparisons are difficult to make for several reasons, and they are ultimately somewhat besides the point. What is clear from research is that pay matters a great deal for attracting and keeping effective teachers, and that, in turn, affects student outcomes. Put simply, poor pay makes it harder to recruit qualified people and less likely that they’ll stay in the classroom — no wonder Oklahoma is facing a teacher shortage and turning to uncertified teachers.

Some argue that pay is not all that important because teachers don’t enter the profession for the money or because other issues, like working conditions, take precedence. But even if true, neither argument negates the need for decent compensation.

“We know why we enter this profession, which is, we most certainly want to have an impact on the lives of children,” Sheehan said. “But what we do is not mission work. We are professionals, and there are bottom lines to be had.”

Meanwhile, critics of traditional teacher pay schedules argue that there should be more emphasis on connecting compensation to performance — maybe Sheehan, a teacher of the year, should have gotten a raise, but not his less effective colleague down the hall, the argument goes. In fact, there is a solid case for performance pay — but not in lieu of reasonable base pay. For instance, Washington, D.C., schools pair one of the most robust and apparently successful performance-pay systems with a starting salary of more than $50,000.

At the root of teachers’ poor salaries is limited spending on schools, including recent cuts.

“The bigger picture of all of it is that the state is not funding public education,” Sheehan said.

Between 2008 and 2016, Oklahoma spending per student by the state decreased by 25 percent. (This doesn’t account for local spending, but through 2014, combined state and local spending is also down.) An analysis by the Education Law Center, a group that backs school-funding reform, gives Oklahoma a “D” in its funding effort, based on how much a state spends on schools relative to the size of its economy. Overall, Oklahoma spends $6,700 per pupil, significantly less than neighbors like Kansas ($9,422), Arkansas ($8,281) and Texas ($7,404).

There has been talk in the state legislature about raising teacher pay for a while, but it’s not clear whether anything will happen — which is what led to the ballot initiative in the first place.

Sheehan isn’t sure how long he’ll stay in the profession. He and his wife, also a teacher, just had a baby, which puts financial pressure on their family.

“We knew what we were getting into — we’re both educators, and we knew that we would struggle — but when you bring kids into it and you’re talking about day care expenses,” he said, “you realize, for me as a 31-year-old adult with his master’s … I don’t want to keep doing this perpetual struggle until I’m 60.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)