Why Nearly Half of Black Students Have Considered Stopping College

Gallup report explores barriers Black students face obtaining degrees, including family, working responsibilities and racial discrimination

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

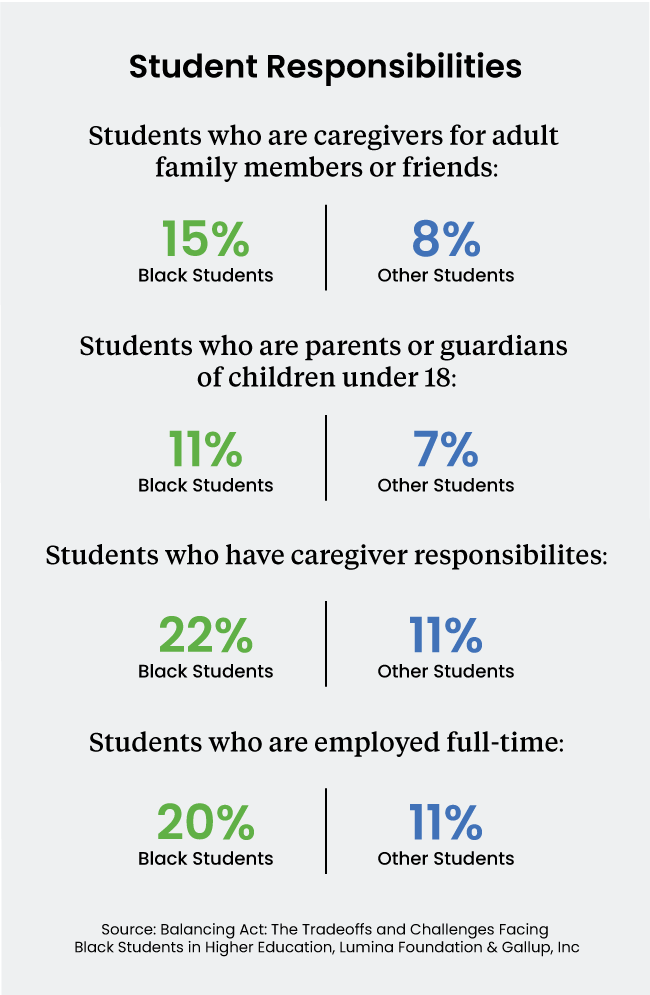

From balancing full-time work and caregiving for family at twice the rate of their peers, to regularly feeling unsafe because of racial discrimination, Black students are forced to navigate disproportionate challenges while earning a college degree, according to a new national report.

And 45% of Black students considered stopping their coursework in 2022, weighing dropping out completely or taking a leave, according to the findings.

The report from Gallup and the Lumina Foundation provides critical insights into what higher education practices impede them from post-secondary success. Higher education officials could revise childcare, housing and financial aid to better support students who are not childless, financially supported 18-year olds.

Balancing Act: The Tradeoffs and Challenges Facing Black Students in Higher Education is the first in a series to be released this year exploring the state of higher education by student subgroups and key issues such as mental health and the value of post-secondary education. Over 12,000 students between 18 and 59 shared insights, including 1,106 Black students.

Most telling, according to researchers, were data showing the external responsibilities put on Black students and how frequently they experienced discrimination. Many expressed feeling psychologically or physically unsafe, feeling that nothing will come of, for example, reporting peers or faculty for discrimination, said Courtney Brown, vice president of impact and planning at the Lumina Foundation.

“These data help us to better understand why we’re seeing the enrollments decreasing at a time we need to see those enrollments increasing,” said Brown. “These two barriers are real, and it’s causing students to think about stopping out or never enroll in the first place.”

Institutional and financial barriers have created a troubling reality: Black students have the lowest six-year degree graduation rates of any racial or ethnic group, at about 44%, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Student response data also showed how institutions can combat the trends by boosting financial aid and offering night or remote courses, revising requirements to live on-campus.

But change starts with a reality check.

“Most policymakers, my guess is if you ask them who college kids are, they think of somebody who goes to college at 18, they live on a campus for four years and then they graduate,” Brown said. “We have been trying to educate policymakers about today’s students. How do you think about childcare on campus?”

It’s common, for instance, for colleges to limit scholarships to full-time students living on-campus, according to Brown. But the practice disproportionately denies financial aid to Black students, more likely to have working responsibilities that prevent them from enrolling full-time, and more likely to be parents, ineligible for on-campus housing.

Findings from surveys and interviews conducted last fall suggest institution type has a large impact on Black student wellbeing, too.

Black students in associate degree programs are more likely than peers in certificate or bachelor’s programs to feel that their professors care about them.

At the least diverse schools, roughly one in three feel unsafe and face regular discrimination — most rampant at private, for-profit schools and short-term credential programs.

The Gallup-Lumina team told The 74 that institutions often don’t do enough to curb interpersonal and classroom practices that discriminate, like out-of-date curriculum that excludes Black scholarship or worldviews.

In order to hold staff accountable for discriminatory acts, according to Brown, institutions could adopt zero-tolerance policies and overall, “be harder when it happens.”

Kia, a Black student aged 30-44, recalled a time race impacted university administration’s handling of a disagreement.

“I’m Black and this person was Caucasian, and because of the person’s smaller stature and voice, [the university administration] just automatically assumed that I’m the one who started this verbal disagreement when it ended up showing that it was her,” Kia told researchers. “I’m not an aggressive person, but they automatically assumed [it was me].”

Her experience mirrors that of many college-bound Black students today: misunderstood and unsupported.

“Institutions need to be student ready. And they’re not. These data show that they’re not,” Brown added. “If they can’t support the full student, if they’re creating a hostile environment for their students, they’re the ones that are failing them.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)