Why Is 1 in 5 Supes Named Michael, John, David, Jeff, James, Chris, Brian, Robert, Mark or Steve?

White: Lab's data tracker is gathering information on every district in the U.S., offering valuable insight into gender gaps and what to do about them

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

If you find yourself in a room full of public school district superintendents and are having trouble remembering someone’s name, pick from this list of 10 and you’ll have a pretty good chance of guessing right: Michael, John, David, Jeff, James, Chris, Brian, Robert, Mark or Steve.

These are the first names of 1 out of every 5 superintendents in the United States, according to new analyses drawing on the first-ever National Longitudinal Superintendent Database.

In fact, the number of male superintendents with just 15 first names is equivalent to the total number of women in that role in the entire nation.

Nearly 10 years ago, The New York Times reported a similar trend among large companies: More S&P 1500 firms were run by men named John than by women in total. As the founder of The Superintendents Lab and an assistant professor of educational leadership and policy, I am alarmed by this similar dynamic in K-12 education, a field in which 77% of teachers and 56% of principals, but just 29% of superintendents, are women.

Developing and implementing policies, practices and programs to address such gender inequities can be challenging without sufficient data to understand trends, patterns and root causes. Yet, no organization or entity has consistently collected data on superintendents in every school district in the nation over time.

AASA, the School Superintendents Association, tracks annual data via its Salary and Benefits Survey, but its anonymous nature does not allow individuals to be followed over time. ILO Group tracks superintendents, but only in the 500 largest districts.

While some state departments of education gather longitudinal data on superintendents, many charge exorbitant fees for access. Where the information is free, it is often out of date.

Though there is a fee for outside researchers, one state that has excelled in collecting and analyzing this data is Texas. The University of Texas at Austin’s Education Research Center houses one of the largest and most complete state longitudinal data systems, which includes information about superintendents. A team from the university’s Texas Education Leadership Lab recently published a comprehensive report on the state’s superintendent workforce from 2010 to 2021, offering powerful insights into racial and gender disparities and suggesting ways to change policy and practice to advance diversity.

Even so, the information is limited to the confines of the state; superintendents who move across borders cannot be tracked.

In the absence of national data, I launched The Superintendent Lab in 2022 to serve as a central hub for research and the home of the National Longitudinal Superintendent Database. This is updated annually, which contributes to a key goal of the lab: to serve as a training ground for undergraduate and graduate students interested in large-database collection, cleaning and analysis. The lab’s research assistants spend more than 400 hours a year identifying superintendents in every K-12 public school district in the United States. With its most recent update for 2023-24, the database currently houses more than 65,000 data points — allowing for a thorough understanding of superintendency.

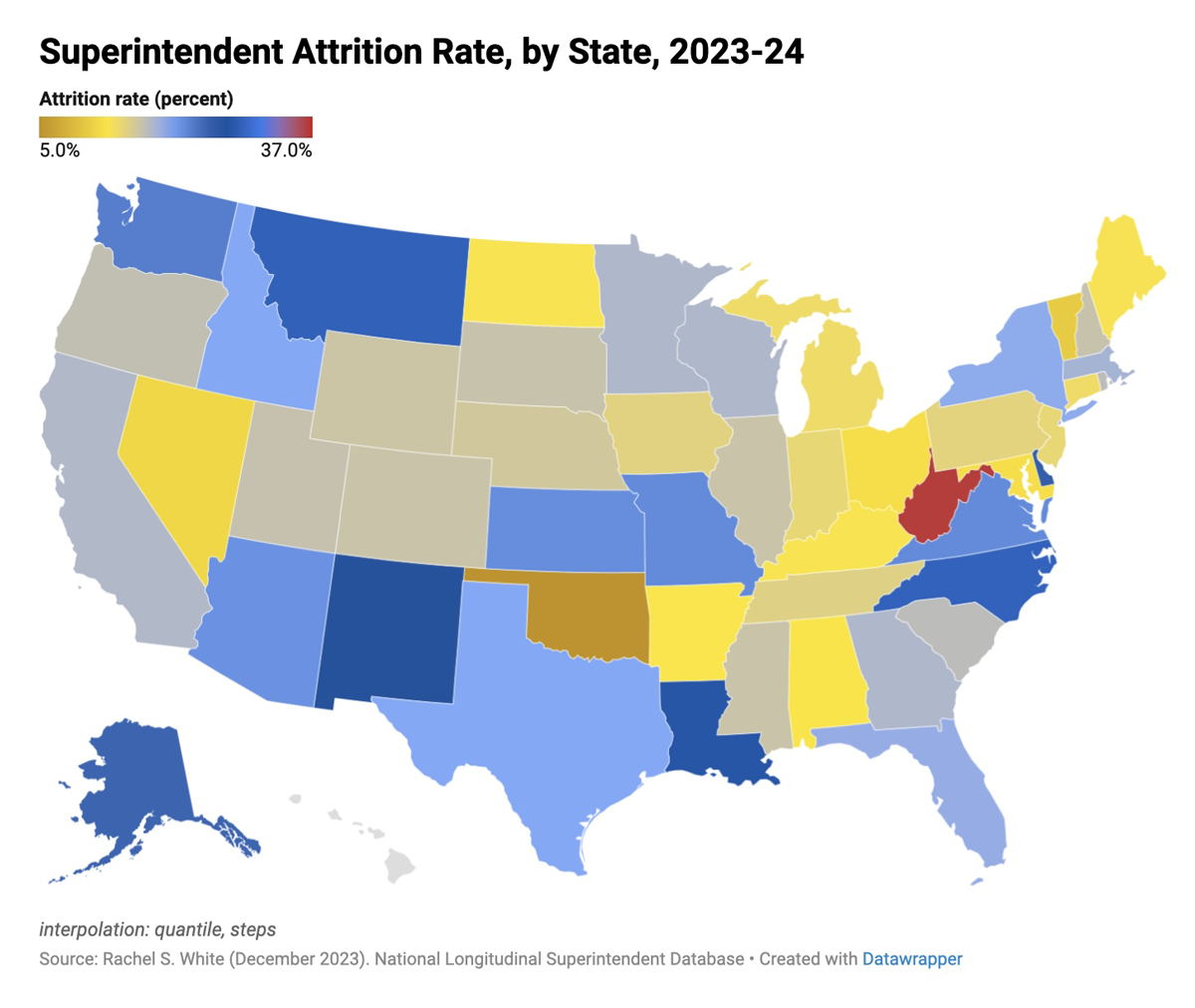

For example, analyses using the database released last month revealed that superintendent attrition rates were over 20% in 14 states this past year. Another set showed that, over the last five years, male superintendents were replaced by men 50% of the time, while women replaced female superintendents 10% of the time. A man replaced a woman 18% of the time, and a woman replaced a man 22% of the time.

That women are taking over superintendent positions held by men at a slightly higher rate than men are replacing women is a promising sign for narrowing the gender gap. Yet, the pace feels glacial: Nationwide, the average gender gap closure rate is 1.4 percentage points per year. At this rate, equality might be attained sometime around 2039.

The database can help policymakers and stakeholders identify trends and patterns in superintendent attrition and gender gap closure in specific states or regions, or with particular demographics. But, more importantly, it can target areas for further exploration: What is happening in places where attrition has stabilized? Which states and districts are excelling at hiring and retaining women, and why? What are the root causes of superintendent attrition?

Still, there are limitations. For example, given findings from the Texas Education Leadership Lab’s report, there is a strong need to more broadly understand inequities at the intersection of race and gender. Currently, the database does not have the capability to examine these at a national level, due to a lack of publicly available information on superintendents’ racial identification.

Moreover, attention should be given to representation among superintendents who have disabilities, are linguistically diverse and identify with the LGBTQIA+ community. While acknowledging the importance of minimizing mandatory reporting requirements, policymakers and practitioners should prioritize thoughtfully crafted efforts to collect superintendent demographics.

Public schools are often touted as laboratories of democracy, places where young people learn leadership skills to participate in a democratic society. Yet, what students currently see is that leadership positions in K-12 school districts are reserved primarily for people named John, Michael and David. With comprehensive national data, policymakers, superintendent support organizations, school boards and search firms can work alongside researchers to target support toward places where the gender gap is widening, and learn from those that are making strides toward equality and equity in superintendent hiring and retention. Without this collaborative commitment, efforts to envision data-driven efforts to improve superintendent diversity will remain limited.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)