Whitmire: Why the Charter Cap Fight in Massachusetts May Have Sparked a Tidal Wave of New Parent Applications

-

Are we looking at more Bostons emerging, where the odds of winning a charter seat are now 1 in 16?

-

And, if that’s the case, what do those spiraling odds say about the commonly embraced American goal of giving equal opportunity to all?

Last fall, the Massachusetts teachers unions quarterbacked a brilliant campaign to maintain a cap on the number of charter schools. Keep-the-cap lawn signs were so plentiful, they might have been mistaken for the official state bird.

And convincing thousands of suburbanites, most of them unaffected by charters, to embrace their cause, was pure genius.

There’s just one small problem with their winning campaign: They failed to cap the attraction charters have for urban parents.

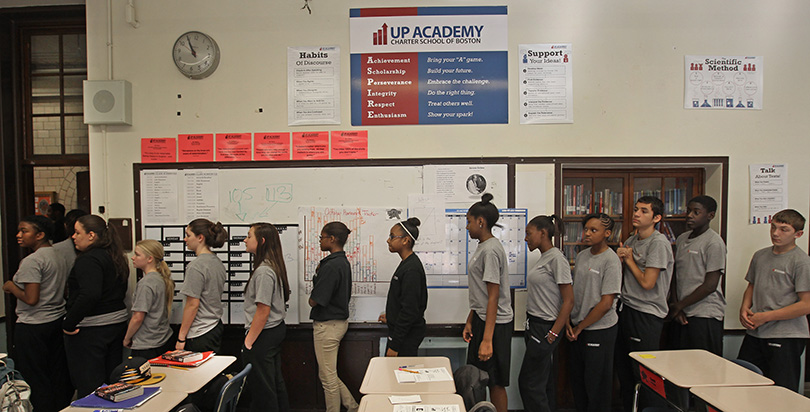

As if in an exasperating whack-a-mole game, those parents popped back into view this week, signing up for charter schools in record-breaking numbers: The 16 Boston charter schools using a new online application received 35,000 applications for the 2017–18 school year, compared with 13,000 the year before.

Problem is, thanks mostly to that cap, there are only 2,100 seats available in those schools.

The surge in charter applications probably says little about the cap-the-charters vote. The low-income, minority parents in Boston who seek out these charters — along with the parents on charter waiting lists — were always minor players in the statewide vote. The vote was more a test of how much sympathy they could win from suburban and rural voters. (Answer: not nearly enough.)

But those strong application numbers, matched by a very limited supply, raise a sensitive question about where the country is headed. Nationally, the growth curve for charter schools has started to flatten out — but with no sign of flattening interest for charter schools among parents.

In a city such as Boston, which boasts the highest-performing charter schools in the country, failing to win a seat at a top charter can be especially painful. Take as an example Brooke Charter Schools, which are possibly the nation’s highest-performing charters.

Brooke consists of three middle schools and a brand-new high school. Landing a seat here means your child will graduate from a school that performs as well as the best suburban schools, even though nearly all its students are low-income minorities.

Roughly translated, getting into Brooke is the same as being awarded a $2 million house in a pricey suburb such as Newton (plus enough money to pay the tax bill). So, what are your odds? Brooke just got 4,327 applications for 180 spots. That puts your chances at 1 in 24.

There are some qualifications in the data. Some of this surge may be due to the new online application form, which makes it easier for parents to tick off multiple schools they would like their children to attend. Charter critics suggest that waitlist figures always include bad and outdated data.

But the fact that 9,200 individual students applied means that multiple box checking can’t account for the doubling in applications, say charter advocates, citing MIT studies of past enrollment lotteries. Although there are no apples-to-apples comparisons to the number of applicants from the year before (the online process is new), the studies suggest the 9,200 figure is roughly double the number of applicants from the prior year, charter advocates argue.

Any way you look at the data, more students applying to more charters is a clear sign of demand — a demand that wasn’t anticipated after the bruising, successful anti-charter campaign waged last November.

In fact, many charter leaders believe that failed referendum prompted the surge. Thanks to that avalanche of press, parents for the first time learned of the option of enrolling their children in higher-performing schools.

All this is playing out amid a national campaign to declare a moratorium on charter schools. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People has joined the teachers unions and many leaders of traditional school districts in appealing for a moratorium — a sign that the popularity of the charter school movement (there are now more than 3 million students in 6,900 charter schools, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools) is having a significant impact on enrollment in traditional districts.

The moratorium movement is gaining strength just as charter school growth has started to level off for a variety of reasons. Annual growth rates of 6 to 7 percent a year for the past two decades have now dropped to 2 percent.

The political opposition is part of the reason behind that drop, along with other factors such as limited startup money, limited facilities, and a desire by both charter groups and charter authorizers to focus on quality rather than growth.

But what we’re seeing in Boston signals that the slowing growth may create painful dilemmas for urban parents who want exactly what wealthier parents seek for their children: great schools that can lead to better opportunities. There are plenty of traditional high-performing schools in urban districts, but not enough. And most urban parents lack the means to move to the suburbs to find more of those schools, leaving charters as their best option.

Boston is not the only flashpoint where this is likely to emerge. Take Los Angeles, which is enduring hand-to-hand political combat over charters. Critics say charters are pushing the district perilously close to bankruptcy as more than 100,000 students have left the district since 2006 — a loss of more than 20 percent. (Are charters to blame? About half of those enrollment losses can be traced to charters.)

Should anti-charter candidates prevail in the current board elections, a Boston-like cap could settle over Los Angeles. And in a district that is home to the largest number of charter schools in the country, limiting families’ access to schools that outperform district schools with similar student populations would be a detriment to students.

There’s no guarantee that Boston-like dilemmas will start popping up in Los Angeles and elsewhere. But the economic principle of scarcity driving up demand is beyond dispute.

Seems like just a matter of time before the moles start popping up elsewhere.

Richard Whitmire is the author of The Founders, a book about the origins of high-performing charter schools, and several other education books.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)