In early October technicians working the master controls at local TV stations across Massachusetts will unleash a torrent of education issue ads – the first shots fired in what is likely to be one of the priciest school battles ever seen.

The conflict concerns a relatively simple question that will appear on the Massachusetts ballot in November: should the state lift the cap on the number of charter school seats it permits to allow 12 new or expanded charters a year?

But there’s nothing simple about this fight, which is ripe with national implications and likely to draw in national combatants.

The stakes: If the teachers’ unions and district superintendents can stop charter schools in Massachusetts — the state that boasts the highest performing charters in the country — then charters are at risk everywhere.

Blocking them in places such as Florida and Ohio, where low-performing or corrupt schools have made headlines over recent years, should be easy compared to Massachusetts, where some charters are so effective they have erased racial learning gaps.

Political insiders believe the vote will be close. On one side are the parents of the 36,400 students already in charters, combined with the parents of the more than 30,000 kids on wait-lists across the state, who are likely to vote to lift the cap. On the other side: a very high percentage of voters in the union-friendly Pioneer Valley in Western Massachusetts are likely to vote against lifting the cap.

Ironically, the fate of the referendum will probably come down to a unique set of swing voters: the suburban centers along the I-495 ring outside Boston that have no dog in this fight. Their schools are unaffected by charters.

To put the question bluntly: Will the well-off white residents of Wellesley, Lexington, Newton, and Hopkinton vote to open up more charter school seats for low-income black and brown students from Roxbury, Dorchester, East Boston, and Mattapan?

It’s unclear.

Photo: Barbara Madeloni

The players

In this first state referendum anywhere on whether to increase the number of charters, the insiders I interviewed believe the anti-charter side has a slight edge — despite opinion polls suggesting the public favors charters.

Why? Charter opponents have formidable ground forces, starting with the Massachusetts Teachers Association. In Western Massachusetts, home to MTA president Barbara Madeloni (whose middle name appears to be “fiery,” based on the many newspaper profiles describing her as such), the union is successfully rolling up a string of city councils and other elected boards with anti-charter votes.

An example: on April 14 Madeloni spoke before the Easthampton City Democratic Committee as part of the Save Our Public Schools anti-charter campaign. She said the district there just lost $750,000 as a result of parents choosing charters (Bay State districts get reimbursed roughly 40 percent of the per-pupil funding). She warned of growing losses if charters were allowed to expand.

Twelve days later the Easthampton City Council voted 7-0 to oppose lifting the cap. What’s notable here is that the vote was taken seven months before the referendum — in other words, long before anyone even knew if a legislative compromise might make a referendum unnecessary.

That’s how thorough the anti-charter ground game is.

As of mid-June, that same scenario had played out in roughly 30 communities, according to charter supporters, who can’t match the union’s numbers or clout with local boards.

There’s another reason why the MTA is so motivated, though it sometimes goes unmentioned: most charters eschew union teachers. (Madeloni declined to be interviewed for this article, but her strong opinions about charter schools are available on YouTube.)

The union’s work is echoed by anti-charter advocacy on local school committees (that’s what school boards are called here). Given their community roots, the influence of the school committee members is important. Like the unions, they prefer that all the education tax dollars stay in traditional districts.

The third powerhouse working against the referendum are the state’s 275 influential district superintendents, who also want funding to stay where it is and can easily find ways to convey their sentiments to parents. All it takes is a town hall session at a school to discuss campaign issues.

The considerable firepower of these groups will be matched against charter supporters —mostly low-income parents in Boston and smaller numbers of rural/suburban parents. (One exception within Boston: many white parents in better-off Jamaica Plain, who worry that a charter expansion could undermine their neighborhood schools and the exam schools.)

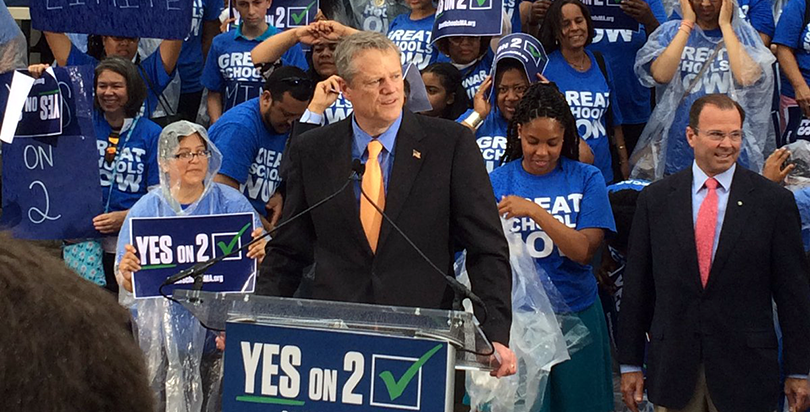

The pro-charter camp has powerful backers, as well, including Gov Charlie Baker, who spoke in favor of the cap lift at a State House rally last Thursday, as well as wealthy business backers picking up the tab for TV buys to support expansion. The business community believes charters will help build an educated work force in the state.

Both sides will claim to act on behalf of “social justice,” with each howling that the opposition dares to make that claim. And they will spend millions to repeat the point over and over and over.

The union says it has $11 million set aside to fight charters, but it appears that far more will be spent on their cause given the involvement of national unions, which understand the potential of drawing blood here.

That war chest will be matched by the pro-charter camp, vows Marc Kenen, executive director of the Massachusetts Public Charter School Association. Both sides are engaged in a funding arms race that includes national funders, in other words, with each side determined not to get outspent.

“I don’t know where it will all end, but it appears that either side alone might break [spending] records, and together we are going to smash any previous record,” Kenen said.

“I think [the opponents] see this as an opportunity to halt the charter school movement, which they have not been able to do. They also view it from a national perspective. If you can stop charters in Massachusetts, then that’s a huge momentum-turner nationwide,” he added.

While Kenen will rely on TV ads financed by key donors, many of them well-known Boston hedge fund managers, media campaigns funded by financiers have risks. As philanthropist Eli Broad discovered recently when he assembled a group of donors to back a major expansion of charter seats in Los Angeles, it can badly backfire, giving unions an opportunity to warn that billionaires are working to “privatize” education (despite the fact that charters are publicly funded and have public oversight).

Madeloni is undoubtedly aware of the successful pushback campaign against Broad waged by the Los Angeles teachers’ union and school board members alarmed by the city’s plummeting student enrollment figures (which they blame entirely on charters, despite the district’s own studies showing only about half the losses can be attributed to these schools).

For all those reasons, observers appear to favor the anti-charter side. And that makes several Boston charter operators with successful track records and long wait-lists very nervous.

They wonder: will we ever be able to meet the demand?

The issues

The central issue of the campaign, which both the unions and superintendents will highlight, is that districts lose revenue when students leave for charters. The problem, said Thomas Scott, executive director of the Massachusetts Association of School Superintendents, is that districts can’t cut back to absorb the losses when students leave. Costs are sprinkled across classes and buildings, so it’s not possible to have one less teacher, one less classroom, or one less janitor.

Outside Boston, the narrative of poor families seeking charters can also be less clear-cut. Fitchburg, in the central part of the state, is a beleaguered, predominantly Latino and very poor community that has lost its manufacturing. But schools superintendent Andre Ravenelle says the district has invested deeply in offering students a rigorous, college-prep curriculum. Losing more motivated, better-off families to charters, along with the funding that goes with them, would devastate his programs, he said.

This is where the pro-charter side asks: well, why can’t you downsize? School districts have been upsizing and downsizing for decades, long before charter schools arrived, they argue.

Complaints by Massachusetts district leaders that they are insufficiently reimbursed for students who leave for charters may make charter supporters from other states shake their heads. Massachusetts superintendents seem barely aware that their 40 percent reimbursement deal is the sweetest in the nation. Only five states reimburse districts at all for losing students to charters; with Massachusetts the most generous by far. Elsewhere, superintendents are expected to cope with student enrollments that rise and fall.

And at least in Boston, the union and leaders of the traditional district will have a hard time making a credible case they are being hurt by charter schools, concluded a recent study by the respected and nonpartisan Boston Municipal Research Bureau.

But those aren’t superintendents’ only grievances.

Consider the impressive scores documented at charters attended by poor and minority children. You can’t compare charter scores with district school scores, says Scott, they are apples and oranges. Parents choose charters, he said, which makes their student body more selective.

“I was the superintendent of a high-performing district and I can tell you that parent involvement may be the most important factor,” he said. “When you have parents selecting where their children go to school, then they have an investment in that.”

He added that charters benefit from having fewer special education students and English Language Learners.

Scott’s contention that charters get slightly better students because parents select them —even if those students are poor— is probably stronger than the special education and ELL argument.

Enrollment numbers of high-needs students are rising in Massachusetts charters, advocates point out, and a recent MIT study found that Massachusetts charter schools do a far better job with those students.

Most of these arguments are inside baseball, however.

It’s unlikely that lots of detail about lifting the cap will matter to voters as they head to the polls with Hillary-versus-Donald on their minds, not to mention questions about legalizing marijuana, granting farm animals a less harsh existence, and whether the Common Core standards should be revoked.

The charter players

The November vote will not kill charters in Massachusetts; it’s strictly about whether to expand the state limit by a dozen new schools and/or expansions of existing ones. That means the charters with the most at stake are small, lesser known schools ready to grow. Two Boston charters that fit the description: Boston Prep in Hyde Park and Helen Y. Davis Leadership Academy in Dorchester.

The educators who lead these schools are nose-to-the-grindstone types who sweat every detail of their students’ days. Political intrigue makes them flinch. During interviews, both leaders sighed and wished the money being spent on the political fight could be spent on kids. But they also know the fight can’t be avoided.

Boston Prep runs a single school, with 415 students in grades 6-12. The school serves the high-poverty, heavily minority neighborhoods of Hyde Park, Roxbury, and Dorchester. For the sixth year in a row, 100 percent of its graduates have been accepted into college and, based on its five graduated classes, 85 percent of Boston Prep alumni are on track to graduate within six years.

That track record helps explain the demand to get into Boston Prep. This past year, 274 students applied for its 50 sixth-grade seats, and 475 students applied for its 25 ninth-grade seats.

Photo: Sharon Liszanckie

Sharon Liszanckie, Boston Prep’s executive director, has a plan to make a dent in the wait-list: double the number of students in grades 6-12 and add a fifth grade. Adding that fifth-grade year would give her students, who arrive at the school between two and three grade levels behind, a full two years to catch up on their academic skills before more challenging classes begin in seventh grade.

“Doing that much catch-up in just one year before the considerable jump in rigor in seventh grade is a challenge,” said Liszanckie. A larger school would also allow more teacher specialization, she said, and more course offerings.

The roadblock, of course, is that the state cap currently blocks the expansion. Liszanckie, who once taught seventh-grade math in Wellesley, knows her cap-lift fate rests on those affluent suburban centers around Boston, the parents whose children she once taught.

She’s in a good position to see the “unequal playing field” between places such as Wellesley and Hyde Park. “Your zip code should not justify what educational opportunities and resources you have available to you,” she said.

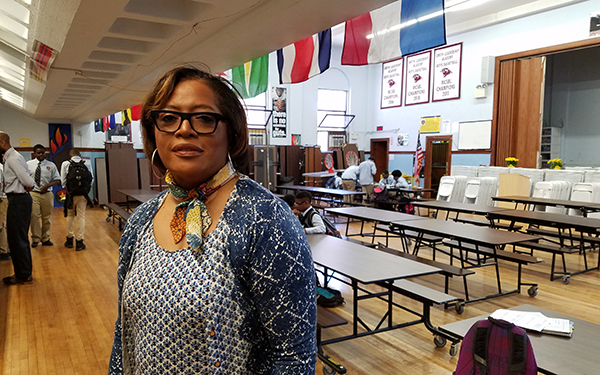

Photo: Karmala Sherwood

Karmala Sherwood, who runs the Afrocentric Helen Y. Davis charter school, can make a slightly different case for expanding her middle school, which now enrolls 216 students in grades 6-8. At a time of much hand-wringing over white charter leaders heading up all-minority charters, Davis is an exception: all of its top leaders are African American. Anywhere you walk in the school you find walls used as full-length murals featuring African-American leaders.

Sherwood says 95 percent of her students are high needs and yet they turn in strong academic results.

The school has a wait-list of 250 students for 85 seats, but that isn’t their core argument for expanding into a high school. What’s missing in area high schools, says Sherwood, is the unique culture for African-American students that is found at Davis.

“When the school began in 2003 I was okay with just a middle school,” she said. “We filled that niche and made sure we closed gaps. But then as time went on parents kept saying they really wished we had a high school. They said they liked our sense of making sure students understood culture and leadership.

“The message from us is that [any student] can be a leader. They can be who they want to be. I don’t think they get that message from other schools … We really feel our work is not finished when they graduate from eighth grade.”

But Sherwood’s school is also blocked by the cap.

How will it all turn out?

That’s impossible to predict; these are the days of Trumpism, Brexit votes and Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France. The “elite” leaders are under challenge. Here, though, it’s not clear which side will be seen as the elite. It could be the financiers funding TV ads or it could be the union bosses.

In theory, the wealthy white suburbs will vote to expand charters to help minority kids in Boston. But an aggressive campaign by the unions, with the message that one day charters might threaten suburban schools, could conceivably give these voters second thoughts.

Also in theory, the superintendents and school committees will act in unified opposition. But I found one superintendent, John McCarthy, from the coastal town of Scituate, who plans to vote “yes” on expanding the cap.

As it turns out, McCarthy’s daughter is a veteran teacher for Rocketship charters in San Jose and he has spent time in the network’s schools. Without Rocketship, McCarthy asks, what are the schooling options for East San Jose kids?

In Massachusetts, said McCarthy, “You could save a lot of kids if you opened up the cap a little bit.”

At the Easthampton Democratic Committee meeting, school committee member Peter Gunn offered an insightful comment on the dilemma: He opposes lifting the cap, but he doesn’t take issue with parents who send their children to charters. Rather, he takes issue with those who “created a law which forces families to choose between doing what’s good for their children and doing what’s good for their community.”

That’s a candid assessment of the standoff here: Both the unions and superintendents much prefer the traditional world of schooling, where kids get funneled into a single, traditional district regardless of the quality of the assigned school. The “common school” model is better for the community, they say.

Easthampton charter leader Amy Aron, who runs the Hilltown Community Charter School, sees it differently. “The union feels like it owns the tax dollars. But these are public schools and these are public school children. The money belongs to the child.”

And that’s a key question: Does the money belong with the traditional school districts or the child?

Given the multiple distractions on the ballot — Hillary, Donald, farm animals, and dope — it seems unlikely that question with get the full attention of many voters.

“People won’t be going to the polls thinking of charters,” said Glenn Koocher, executive director of the Massachusetts Association of School Committees. “They will be going to vote for Hillary or Donald.”

As for the charter question, it will probably come down to which side delivers the most effective ad blast in the last hours before the vote.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)