Whitmire: The Wave of Higher Ed Shutdowns Threatens American’s Progress in Getting Low-Income, First-Generation Students to and Through College

Just weeks ago, Brandy Caldwell was finishing up her senior year at Boston’s Brandeis University when she got the notice: The coronavirus was forcing a campus shutdown in two days.

For most students, that meant a hasty packing up and a quick car trip home to their parents. But for Caldwell, 22, it wasn’t that easy.

“I am a homeless college student. I went into foster care when I was 5 years old and aged out when I was 21,” Caldwell said. “Technically, I don’t have a place to go. I have no permanent address. Where was I going to go?”

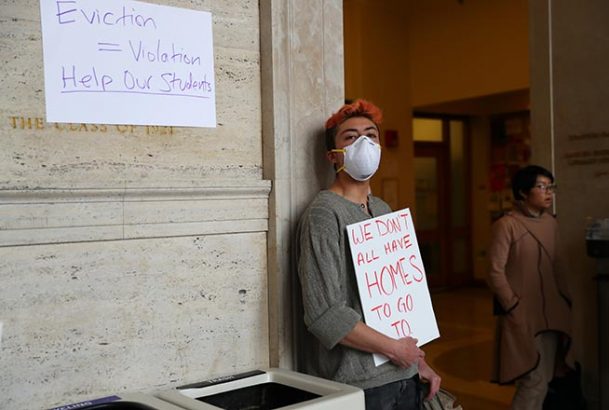

From a public health perspective, the wave of short-notice college shutdowns may make sense. But for thousands of first-generation college-goers — and there are far more of them than ever — the closure of more than 200 schools across the U.S. presents special emergencies. How do I pay for a plane ticket home? How will I replace the income from a campus work-study program? If I can’t afford to return to my four-year college, how will enrolling in a local community college affect my life plans?

The challenges appear serious enough to threaten the fragile progress the nation has made in recent years in getting more low-income students both enrolled in college and earning degrees — progress I laid out in my recent book, The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America.

In that book I describe a college world foreign to most middle-class families, a world where students are one car repair away from dropping out. I tell the story of a student from a small high school in the South arriving at a chilly Pennsylvania campus without sufficient warm clothing. She became so isolated she didn’t seek outside help and almost flunked out her first semester. Finally, the principal of her high school learned of her dilemma and bought her a warm coat and some long underwear.

How many fragile students are buffeted by sudden changes such as a campus shutdown? A 2018 report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce concluded that 70 percent of full-time college students hold down jobs.

And the campus poverty level, which usually translates into worries about being able to afford meals, is far higher than most people imagine. A 2019 survey out of Temple University laid out the problem. An excerpt from that report:

During the 30 days preceding the survey, approximately 48% of students in two-year institutions who responded to the survey experienced food insecurity, with slightly more than 19% assessed at the low level and slightly more than 28% at the very low level of food security. Approximately 41% of students at four-year institutions who responded to the survey experienced food insecurity, with slightly less than 18% assessed at the low level and slightly less than 24% at the very low level of food security. More than half of survey respondents from two-year institutions and 44% of students from four-year institutions worried about running out of food. Nearly half of students could not afford to eat balanced meals.

For Caldwell, a graduate of a KIPP charter high school in Washington, D.C., the first worry was “Where do I go?”

“I called my KIPP Through College adviser,” Caldwell said, “and she told me to calm down, we can figure it out.”

Like most top charter school organizations, KIPP maintains a staff that tracks their alumni in college. In KIPP’s case, that’s 15,000 students, almost all of them low-income and minority. Caldwell’s adviser, Kamilah Holder, advised her to ask Brandeis for the same accommodation afforded to international students: dorm space during the shutdown. Caldwell did, and that was granted.

With most of the Brandeis student cafeterias closed, the next worry was food. Caldwell also appealed to KIPP for grocery help.

As with other charter networks, KIPP does special fundraising for emergencies such as this. Within a few days, KIPP raised more than $135,000 and started processing claims. That total has since grown to $148,778, with the network to date giving out 294 grants at an average amount of $247 per grant. For its alumni, 44 percent of those grants went to food assistance, 23 percent to computer and tech needs and 18 percent to transportation.

“I got a response within 20 minutes, and 20 minutes after that I got money through PayPal,” she said “Kamilah is like my mom; I love her.”

Gabriela “Gabby” Zorola graduated from an IDEA charter high school in Texas’s high-poverty Rio Grande Valley and improbably ended up at Boston’s Northeastern University. “They gave me the most financial aid money. The first time I ever saw the campus was at freshman orientation.”

But she quickly adjusted to the campus, thanks mostly to the Latinx Student Culture Center she discovered. First came the announcement that the university was shifting online; then came the shutdown notice: How to get home? “It was horrible for me,” Zorola said.

IDEA stepped in to pay the airfare, but her worries haven’t lessened. She chose a challenging major, bioengineering, and now she faces the prospect of taking physics online with uncertain outside help. What about labs? “I know it’s going to be much harder.”

In theory, she could transfer to nearby University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, but she was counting on the advantages offered by the prestigious Northeastern University. Aside from the school’s reputation, the location is priceless. Boston is at the center of bioengineering. “Boston has everything, right here.”

Sancia Celestin, 21, whose family is Haitian, grew up in Virginia’s Hampton Roads area and ended up at George Mason University in northern Virginia. There, she’s a senior and also serves as president of the campus’s student group for first-generation college-goers. She is majoring in psychology and wants to work in education policy.

Celestin’s challenge is paying her share of an off-campus apartment. Her rent money came from a campus work-study program in a testing center. When the campus shut down and shifted to online learning, her job evaporated. And although she has moved back home to Hampton Roads, she still owes rent and utilities. “I don’t have much choice other than paying it.” She is asking the leasing agent for a grace period on rent.

Paulina Pereira Miranda, who graduated from an IDEA high school in Texas, never imagined she’d attend school as far away as Kalamazoo College in Michigan, but that’s where she ended up — the result of a generous scholarship offer. Her biggest surprise about Kalamazoo: When she went to a Mexican restaurant there, they served hard-shelled tacos that appeared to have come out of a box. “No, those are like fake,” she told her friends with a laugh.

Her mother is a house cleaner, her father a truck driver, and she would be the first college graduate in her family. A freshman there, she was shocked by the sudden closure notice. “I was scared. I didn’t know what to do.” Had IDEA not picked up her plane fare home, she guesses her father would have driven the roughly 1,273 miles — and back again — from Austin to Michigan to get her.

Not all universities are simply flushing out all their students. Many allow low-income students to stay. And the high schools that track their alumni — and arrange assistance — are proving to be lifelines.

But if those lifelines don’t broaden, the “B.A. Breakthrough” will become a sad retreat.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)