Osborne & Langhorne: Where Politics Make Charters Difficult, 9 Tips for How Urban Districts Can Create Charter-like Schools — and Improve Their Success

Over the past 15 years, the fastest improvement in urban public education has come from cities that have embraced charter schools’ formula for success — autonomy, choice, diversity of school designs, and real accountability for performance. To compete, many districts have recently tried to spur charterlike innovation and increase student achievement by granting their school leaders more autonomy.

District-run autonomous schools are a hybrid model, a halfway point between charters and traditional public schools. They’re operated by district employees, but they can opt out of many district policies and — in some cities — union contracts.

Our recent analysis of state exam scores from 2015 and 2016 in Boston, Memphis, Denver, and Los Angeles showed that public charter schools outperformed both traditional public and in-district autonomous schools on standardized tests in three of the four cities studied. In the one exception, Memphis, the district concentrated its best principals and teachers in, and provided extra funding and support to, its autonomous iZone schools.

However, when the political landscape makes chartering difficult, in-district autonomous models may be the second-best option. Districts can increase the success of these schools if they heed these nine lessons learned by the four cities in our study.

Protect unrestricted autonomy

When autonomy is limited, so is principals’ ability to meet students’ needs. Districts need to give these schools unrestricted staffing and budgeting authority.

Staffing autonomy allows school leaders to hire effective staff who believe in their school’s vision, and to evaluate staff based not only on performance but also on cultural fit. Forced placement of teachers not only harms student learning; it can also undermine a school’s culture. As one autonomous school principal in Los Angeles said, sometimes a principal needs to “lose a teacher and save a school.”

Budgeting autonomy enables principals to hire staff according to their schools’ unique needs — for example, bringing on additional guidance counselors rather than a dean. Leaders who control their own budgets can fund hands-on learning, purchase tablets for blended learning, hire a full-time substitute teacher, or employ any of a hundred other innovations.

Create a district office or independent board to support and protect autonomous schools

Autonomous school leaders spend a significant amount of time fighting to exercise the autonomies they have been promised. Sometimes, they get so frustrated, they leave. Districts with autonomous schools should create a central unit dedicated to supporting them, defending their autonomy and advocating on their behalf when disputes arise.

An alternative is to create a 501(c)3 nonprofit board, as Denver has. These boards are appointed, not elected, so they are free to make decisions that benefit students and schools without fear of political backlash. The boards oversee school progress, provide financial oversight, select school leaders and evaluate their performance, and protect them from district micromanagement.

Articulate a district-wide theory of action and secure buy-in from central office staff

Changing the mindset of the central office requires a huge cultural shift. Autonomous schools necessitate that many parts of the central office do things differently, so employees need to believe in the connection between school autonomy and student success, rather than seeing autonomous schools as an inconvenience and/or a challenge to centralized authority. District leaders need to openly discuss why they believe school autonomy will produce better performance, share this information publicly with school leaders, central office employees, teachers, and the community — and constantly reinforce the message.

Turn some central services into public enterprises that must compete with other providers for schools’ business

The fastest way to change the mindset of central office staff who provide services to schools — such as professional development, food, maintenance, and security — is to take away their monopoly. When internal service shops have to sink or swim in a competitive market, they almost always swim, because they are much closer to their customers than private competitors are. But, in the process, they increase their quality and reduce their costs.

Authorize district-run autonomous schools like charter schools

Rigorous authorization has been essential to the success of strong charter sectors. Districts should use similar processes to authorize their own autonomous schools — allowing only the most promising applicants to open schools and removing those that prove ineffective. A careful authorization process weeds out weak proposals at the beginning, reviews performance along the way, and replaces schools that fail with stronger operators.

Ensure continuous improvement by using a clear system of accountability to close and/or replace failing schools

A common shortcoming among districts with autonomous school models is their failure to impose consequences that create real urgency among teachers and principals — closing and replacing failing schools. Every district should implement a performance framework that requires schools to show academic growth. If they fail, the district should provide additional supports during a probationary period but replace them if they still don’t meet targets. If a school is successful, the district should provide resources and incentives to encourage it to open another campus, as Denver does with its Innovation Schools.

Invest in developing autonomous school leaders

Giving schools autonomy does nothing to help student achievement if school leaders follow district procedures rather than looking for ways to be innovative. Districts need to invest in developing school leaders so they can take advantage of their freedoms. Careful selection of and support for principals has been a large part of the Memphis iZone’s success. Novice principals there are placed in partnerships with experienced principals, meeting over the summer and throughout the year to collaborate on strategies for leveraging autonomy to achieve results.

When possible, give families a choice of autonomous schools

Families and students who can choose their school tend to show more commitment than children who are assigned to one. Choice empowers them, and people who feel empowered are more likely to give their best efforts. In addition, systems of choice allow for the creation of schools with a variety of learning models, so students can select a school with the culture and curriculum that best fit their needs.

Explore district-run autonomous models from other cities

By examining a variety of successful strategies, districts can find and adapt the model that best fits their political climate and meets the needs of their community.

In addition to the four cities we studied, Springfield, Massachusetts, and Indianapolis, Indiana, have launched interesting in-district autonomy strategies.

The Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership, created as an alternative to a state takeover of several schools, contains nine struggling middle schools and one high school that have been given significant autonomy, overseen by a seven-member board of four state-appointed officials and three locally appointed members. The teachers union negotiated a new contract that includes longer hours, increased pay, and some compensation based on performance.

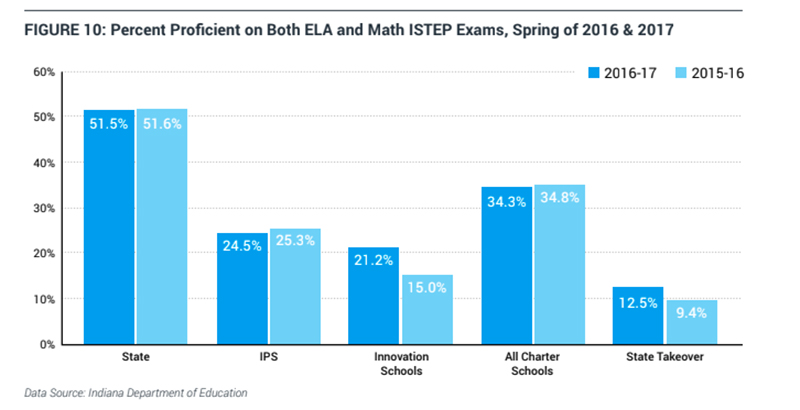

Indianapolis’s Innovation Network Schools, which start with full charter-like autonomy rather than with waivers from district rules, are the fastest-improving in the district. They have the same exemption from laws, regulations, and contract provisions as charters, and while the schools operate in district buildings, the principals and teachers are employed by the nonprofit corporation that operates the school. Each school’s board hires and fires the principal, sets the budget and pay scale, and chooses the school design. The nonprofits have five- to seven-year performance contracts with the district. If schools fail to fulfill the terms of their contracts, the district can refuse to renew them; otherwise, the district cannot interfere with their autonomy.

By following the recommendations above, districts can create self-renewing systems in which every school has the incentives and autonomy to continuously innovate and improve. At the same time, they can offer a variety of school models to families, to meet a variety of children’s needs.

Whether school boards will have the courage to close failing autonomous schools full of unionized district employees will always be a question. The long-term sustainability of in-district autonomy after the leaders who championed it have left is another Achilles’ heel. But if done well and sustained, such schools have the potential to improve public education in urban America.

David Osborne, who directs the Progressive Policy Institute’s education work, is the author of Reinventing America’s Schools: Creating a 21st Century Education System. A former English teacher, Emily Langhorne is an education policy analyst and project manager with the Progressive Policy Institute.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)