Osborne & Langhorne: Can Urban Districts Get Charter-Like Performance With Charter-Lite Schools? The Answer Lies in Autonomy

Over the past 15 years, cities across the country have experienced rapid growth in the number of public charter schools serving their students. In states with strong charter laws and equally strong authorizers, charter schools have produced impressive students gains, especially in schools with high-minority, high-poverty populations.

According to the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) 2015 study on 41 urban regions, the academic gains made by students in charter schools increase with each year students spend at the school. Those who have spent four or more years at a charter gain the equivalent of 108 more days of learning in math and 72 more days in reading each year than their traditional public school peers. In other words, they learn about 50 percent more every year than those with similar demographics and past test scores who stayed in a district school.

Urban districts have spent a lot of time and money trying to compete with the charter sector’s formula for success — autonomy, choice, diversity of school designs, and real accountability. Recently, however, many districts have attempted to replicate parts of it instead. Districts from Boston to Denver to Los Angeles have tried to spur charter-like innovation and increase student achievement by granting school leaders more autonomy.

District-run autonomous schools are a hybrid model, a halfway point between charters and traditional public schools. They’re still operated by district employees, but they can opt out of many district policies and — in some cities — union contracts.

The big question: Can urban districts get charter-like performance with these charter-lite schools?

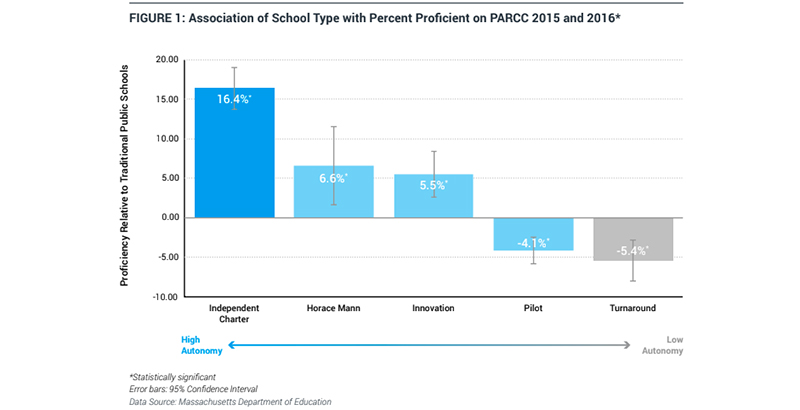

Our new analysis of state exam scores from 2015 and 2016 in Boston, Memphis, Denver, and Los Angeles showed that district-run autonomous schools in these cities sometimes performed better than traditional public schools, but they seldom performed as well as independent public charters. The exception was Memphis. However, the district launched its autonomous “innovation zone” schools by recruiting its best principals and teachers, then gave them extra funding and support. This worked, but it undermined the schools they left behind. It probably explains why Memphis was an outlier.

Overall, our analysis reveals a positive relationship between school autonomy and student achievement. Students can achieve more if those who understand their needs best — principals and teachers, not the central office — make the decisions that affect their learning.

However, not all autonomies are created equal. Most school leaders agree that some kinds of autonomy prove more essential to student success than others. Ranked in rough order of importance, the categories include autonomy over:

1. Staffing: Do school leaders have the power to select and remove their teachers and other staff and determine how to evaluate and pay them?

2. Learning model: Are the schools free to adopt different focuses (arts, STEM, etc.) and learning models, such as Montessori, blended learning, project-based, and dual-language immersion?

3. Curriculum: Are school leaders free to determine their own curricula, textbooks, software, and the like?

4. Budgeting: Can school leaders spend their resources to best serve student needs, or are budget formulas determined by the central office?

5. School calendar and schedule: Are schools allowed to set the lengths and schedules of their school days and years?

6. Professional development: Do school leaders and staff decide what professional development they need, or does the central office?

The amount and type of autonomy available to in-district autonomous schools in our four cities varied. For the most part, these schools had less than independent charters enjoyed. And even when they had autonomy on paper, their leaders often expressed frustration because the district failed to honor all its promises.

At Los Angeles Unified School District’s pilot schools, which had the most official autonomy over staffing of any school model in the district, multiple principals expressed frustration over the district violating their autonomy through the forced placement of unwanted teachers at their schools.

Union contracts often require that districts continue to employ unwanted teachers. When principals don’t hire them, they sit in the district’s reserve pool, collecting salary and benefits. That gets expensive, especially when ineffective teachers remain in the pool year after year. To save money, districts often force principals to hire these teachers.

One L.A. principal also complained about his inability to dismiss an ineffective teacher, despite his alleged autonomy in this area. “The district makes it very difficult to move a teacher once you give them an unsatisfactory performance,” he said, “You have to hold on to that lemon. It takes four to five years to move that teacher. They have damaged a whole cohort of kids by that time.”

The principal of an innovation school in Denver ran into similar problems when he tried to use the budgeting autonomies outlined in his innovation plan. According to his plan, he had the authority to make purchasing decisions. Using a price list provided by the district and one from outside providers, he could decide where to buy transportation, food service, facility management, maintenance, and student services.

Unfortunately, the central office never provided price lists and continued to force its services on the school. When the principal contracted with Mental Health America of Colorado to provide services, the district ordered the company to stop. Officially, the principal had a lot of autonomy, but the reality was very different. Tired of constantly fighting with the central office, he left the district.

In Boston, former superintendent Tommy Chang explained that principals of different autonomous schools reported different experiences with their central office overseers. “Some pilot school principals may say some of their autonomies are being infringed upon; other principals will say they are getting a lot more support from the central office,” he said. This was true in Denver as well: Some central office staff respected school autonomy, while others never quite got the message.

Although principals at iZone schools in Memphis did not feel the district encroached upon the autonomies it promised them, some complained about not having enough. Principals didn’t control most of their budgets, for instance, and they could choose their own curricula and assessments only if their test scores were above a certain level. One former principal of an iZone school said he had only half the important autonomies an independent charter school principal would enjoy. He didn’t have the budgetary freedom to put aides in every classroom, for example. He wanted a full-time psychologist, but the district gave him one only one day a week. And he needed an operations manager but couldn’t move money to fund that position. If he had all the autonomy he needed, he said, “I could do some amazing things.”

The struggle for independence at in-district autonomous schools can be endless, and — even for dedicated school leaders — exhausting. True autonomy appears to be one of the primary reasons that charter schools outperform district-run autonomous schools.

David Osborne, who directs the Progressive Policy Institute’s education work, is the author of Reinventing America’s Schools: Creating a 21st Century Education System. A former English teacher, Emily Langhorne is an education policy analyst and project manager with the Progressive Policy Institute.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)