What a Teacher’s Little Red Book Taught the World About the Tulsa Massacre

'Events of the Tulsa Disaster' continues to educate thanks to the author's great-granddaughter’s efforts to further her legacy.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Much of what the world knows about the Tulsa massacre, one of the most consequential events of state-sanctioned racial violence and displacement in America’s history, started with the work of one woman. Although Mary E. Jones Parrish’s name has made a resurgence in recent history, the impact of her book about the disaster still isn’t fully recognized — a situation one of her descendants is looking to change.

From May 31 to June 1, 1921, Tulsa’s thriving Greenwood district — dubbed “Black Wall Street” by Booker T. Washington — was decimated. One of the most affluent all-Black communities in the country at the time, Greenwood had an estimated 10,000 residents, many seeking refuge from the racial violence in other parts of the United States. Its 35 blocks boasted 121 Black-owned businesses and the nation’s largest Black-owned hotel.

Over less than 24 hours, hundreds of people were killed, more than 800 were injured, and over 1,200 homes and Black-owned businesses were burned and bombed to their foundations, leaving the community with damage amounting to over $27 million in 2021 dollars.

The events leading to the massacre began on May 30, 1921, when unfounded allegations that a 19-year-old Black boy, Dick Rowland, had assaulted a 17-year-old White girl, Sarah Page. The allegations energized White residents of Tulsa as rumors of and plans for his execution spread.

Many argue that the impetus of the massacre was not the allegations, but the way the Tulsa Tribune, a White newspaper, sensationalized the events, weaponizing the afternoon’s headline as more a call to action: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.”

A mob of White Tulsans, estimated to be in the thousands — at least 500 of whom were deputized by the police chief and given weapons — took to the streets of Greenwood.

In the days after the massacre, White media remained complicit in hiding its true nature, naming it a riot and obscuring details. The full number of people killed and true nature of the economic impact remain unknown, but what historians have been able to uncover is due to the work of Parrish, a journalist and typewriting instructor whose 1923 book, “Events of the Tulsa Disaster,” was the first book to be published accounting the massacre.

“Parrish’s work became a vital primary source for other people’s writings,” journalist Victor Luckerson wrote in his recently released book, “Built From the Fire.” “Yet her life remained unknown, even as the facts that she had gathered — such as several firsthand accounts of airplanes being used to surveil or attack Greenwood — became foundational to the nation’s understanding of the massacre. She was, quite literally, relegated to the footnotes of history.”

Parrish’s great-granddaughter Anneliese Bruner is following in her footsteps as a writer and editor but didn’t learn of her connection to Parrish — or the events of Tulsa — until she was in her 30s.

A routine visit to her father, William Bruner Jr., for the holidays was all Bruner had set out for. She arrived at her dad’s expecting the usually jovial and lighthearted man she’d grown up with but found him uncharacteristically serious as he waved her into his room and closed the door behind them.

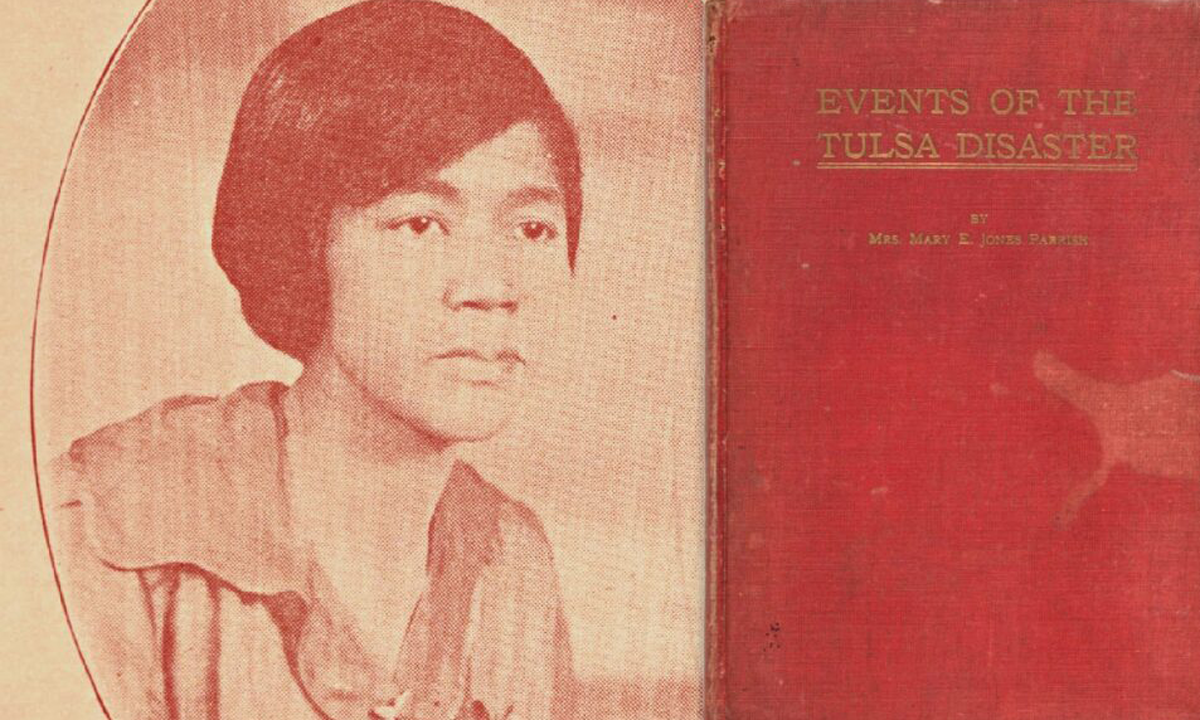

He produced an envelope and out of it pulled a small, red, cloth-wrapped rectangular book that wore its age well and had the words, “Events of the Tulsa Disaster by Mrs. Mary E. Jones Parrish” embossed on the front in gold lettering.

“This is a book your (great) grandmother wrote,” Bruner’s father said, revealing to her for the first time the depth of her ancestry, who her grandmother, Florence Mary was, and why the events of the Tulsa massacre were such an integral piece to her bloodline’s story. “I’m giving this to you. I want you to see what you can do with it.”

When “Events of the Tulsa Disaster” was first published in 1923, it was done so privately by Parrish out of an abundance of caution. Today, few copies of the original work exist.

In 2021, Bruner answered her father’s call, promising to spread Parrish’s work, and worked with the Trinity University Press to secure wide release of the book, titling the new edition, “The Nation Must Awake: My Witness to the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.”

“I want people to know this work,” Bruner told The 19th. “As well as the person who did this work. I want people to see her courage. Her motherliness. Her agency and certainty in herself. Her spirit. … I want them to see her humanity.”

Just two paragraphs into the book, Parrish writes, “How recent seems the beginnings of this little book!” For Bruner, aside from its stature, there was nothing small about the book. She pored through it in one sitting with what felt like a sense of urgency, learning of the horrors of those two days and those that followed, uniting with her great-grandmother all the while.

After the massacre, against the wishes and caution of her friends and loved ones, Parrish stayed in Tulsa to accept a job from the Inter-Racial Commission to report on the events. The commission, created not even a month after the massacre, was an amalgam of what Parrish describes as “fair-minded white” and “no less representative” Black people with the common goal of creating a “greater and better Tulsa.”

Parrish used this opportunity to take a microscope to the events, contextualizing race relations in Tulsa as she interviewed scores of eyewitnesses, cementing the accounts of survivors, salvaging photographs of the ruins and lives lost and even creating a list that would become the foundation of what is known of the economic loss.

Parrish begins her book with her own account. Her knowledge of the massacre began when her 9-year-old daughter, Florence, said, “Mother, I see men with guns.” After waiting for the sounds of the violence to diminish, Parrish wrote that she “breathed a prayer to heavenly father for strength” and escaped with Florence.

The book then details survivors’ accounts, including James T.A. West, a local high school teacher, who recalls being rounded up with other men.

“They (the Home Guard) told me to line up in the street. … They refused to let one of the men put on any kind of shoes. After lining up some 30 or 40 of us men, they ran us through the streets to Convention Hall forcing us to keep our hands in the air all the while. While we were running some of the ruffians would shoot at our heels. They actually drove a car into the bunch and knocked down two or three men.”

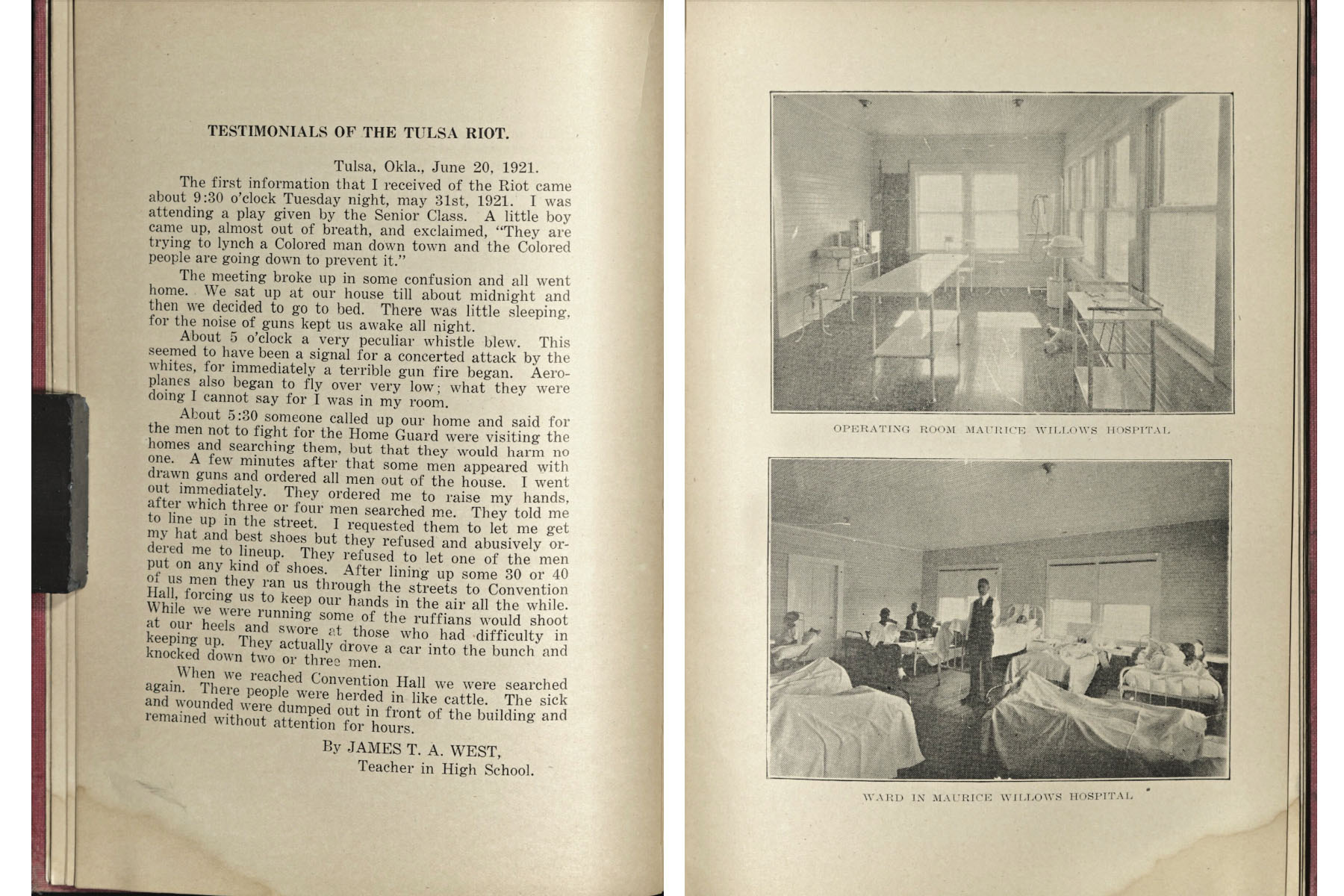

“When we reached Convention Hall we were searched again. There people were herded in like cattle. The sick and wounded were dumped out in front of the building and remained without attention for hours,” West said.

Parrish intersperses her own recollections as well. “I can never erase the sights of my first visit to the hospital,” Parrish wrote. “There were men wounded in every conceivable way, like soldiers after a battle. Some with amputated limbs, burned faces, or bandaged heads. There were women who were nervous wrecks, and some confinement cases. Was I in a hospital in France? No, in Tulsa. One mother was so thoughtless as to burden her infant for life with the name of June Riot.”

“There were to be seen people who formerly had owned beautiful homes and buildings and people who had always worked and made a comfortable honest living all standing in a row and waiting to be handed a change of clothing and feeling grateful to be able to get a sandwich and glass of water,” Parrish wrote.

“Dreamland,” as Greenwood was called for the exceptional economic and social potential it held for Black Americans, was no more. “Soon we reached the district which was so beautiful and prosperous looking when we left. This we found to be piled of bricks, ashes and twisted iron, representing years of toil and savings.”

“We were horror-stricken but strangely we could not shed a tear.“ Parrish writes, “We did not enter there through the section of town, but they brought us through the White section, all sitting flat down on the truck looking like immigrants, only that we had no bundles. Dear reader, can you imagine the humiliation of coming in like that, with many doors thrown open watching you pass, some with pity and others with a smile?”

“It is my sincere hope and desire that this book will open the eyes of the thinking people of America.”

This story was originally published by The 19th.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)