We’ve Surveyed 82 School Districts That Launched Remote Learning Amid the Pandemic. Here’s What Did (and Didn’t) Work This Spring — and What It Means for Next Year

As school districts start preparing for the 2020-21 fall reopening, we at the Center on Reinventing Public Education are wrapping up our survey of responses to COVID-19 and our spring remote learning plan database, and turning our attention to the future.

Districts have undoubtedly learned a lot over the spring as they constructed remote learning plans, improved student online access and developed meal plan supports for families. As this school year winds down, districts will have the opportunity to move from response mode to proactive preparation for the 2020-21 school year in light of COVID-19 constraints.

How well they take advantage of the next three months to develop comprehensive reopening plans and align resources to support their most vulnerable students will determine whether they narrow or widen the learning gaps that have been exacerbated by this crisis.

Below, we present lessons from the first phase of this project that will help school systems support students effectively in the months to come.

After a slow start, districts have come a long way on remote learning

On March 20, we reported that in the first week of closures, the districts we reviewed were focused primarily on school meal distribution plans and student health and safety. About a third (15 of the 46 reviewed) were exploring device distribution, and about half (26 of 46) were sharing links to online general educational resources.

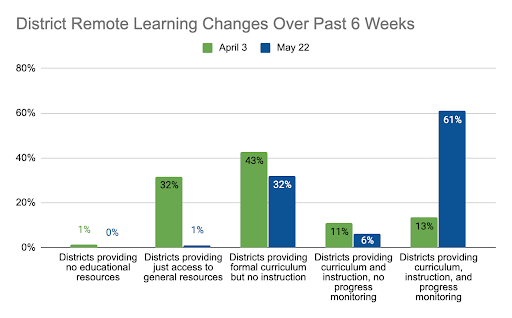

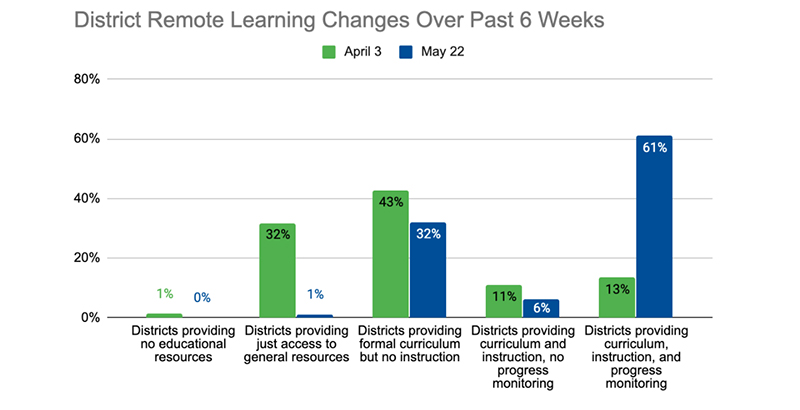

Two months later, 61 percent of a larger sample set of districts (50 of 82 districts reviewed) provide remote learning plans that include formal curriculum, instruction and progress monitoring, and 99 percent of districts we reviewed (81 of 82) are providing students access to a formal curriculum.

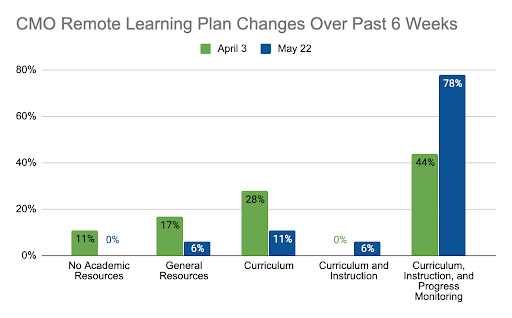

Our review of 18 charter management organizations (CMOs) with at least 10 or more schools demonstrates that they came out the gate with ambitious remote learning plans and have also improved learning plans over time.

The most common learning strategy we observed was pairing formal curriculum assignments with teacher feedback on student work; 77 percent of districts and 89 percent of CMOs we reviewed provide feedback on students’ work for all grade levels.

Some districts rolled out detailed plans, but not until more than a month after schools closed. Other districts and CMOs moved quickly to institute remote learning, including access to instruction, within days of closure. While we did not specifically study the reasons for this difference, publicly available communications indicate that districts’ prior level of preparation, level of centralization and leadership tone likely made a difference in how quickly they could set up remote learning.

Amid this progress, some aspects of remote learning never came to fruition. Just 17 districts, or 21 percent, provide real-time (live) instruction, and only 9 of those districts provide it for all students. Most of the students receiving live instruction are in middle or high school.

Districts did not always indicate how many hours they expected teachers to teach, but they typically recommended 30 to 60 minutes per day for elementary students and three to four hours per day for older students. In general, we found that elementary students are being asked to do more reading, physical activity and self-guided online assignments, and they receive less direct instruction from their teachers.

There is no question that the limited instructional hours and access to live teaching places the burden of learning on parents and families in a new way during remote learning. Elementary school activities are especially dependent on parent engagement. This fall, districts must plan more remote engagement strategies for younger students, especially K-3 children developing foundational reading and numeracy skills.

Inequities have only been exacerbated during COVID-19

Long-standing inequities appear to be widening this spring under remote learning plans. While this database is not a representative sample and does not study district demographics, we do see troubling limitations to educational access across the country.

- Students with special needs and English language learners are often left out

While the majority of districts post general information about their commitment to serving students with special needs, there are sparse public details on what that looks like beyond working one-on-one with families. It is simply not clear how districts’ or CMOs’ remote learning plans are being modified to accommodate students with special needs or English language learners. Coupled with the lack of guidance many states are providing districts on special education, our analysis raises red flags about the level of support students with disabilities received in remote learning — and suggest districts will need to prepare for meaningful compensatory services, intentional efforts to support socialization and an intentional strategy to address lost learning. - Device distribution and connectivity challenges limit access

Most systems — 85 percent of districts and 94 percent of CMOs reviewed — provide devices for at least some of their students, but not enough to guarantee universal access. Only a little more than half of districts (55 percent) and CMOs (61 percent) reviewed provide devices for all students. Shortages have forced some districts to ration laptops, tablet computers or mobile hotspots. Districts make hard choices, prioritizing distribution by family or for older students, which necessarily limits the expectations they can hold for all students. Internet connectivity, not usually a service that districts would be expected to provide, remains an operational challenge that demands city and state attention; 66 percent of districts and 34 percent of CMOs we reviewed are providing some form of hotspot support in the meantime, typically via mobile hotspot devices or community Wi-Fi hubs.

- Traditional student data tracking systems are largely absent

It is not clear whether or how most districts are identifying missing students, much less helping them catch up. Only 32 percent of districts and 61 percent of CMOs we reviewed required schools to track attendance this spring. Districts that track attendance can act on the data by reaching out to absent students and addressing their access challenges. Many posted proud average daily attendance updates to their websites celebrating students’ presence during remote learning. Districts that do not track attendance or require teachers to maintain contact may not know which students are learning and which are not — and are now flying blind as they prepare for fall. Similarly, 51 percent of districts and 50 percent of CMOs we reviewed provide formal grades for all students. Many of those that do rely on pass/fail systems instead of grading students based on mastery of standards or traditional letter grades. While we would expect adjustments to be made to how students receive grades and credit during this crisis, the absence of standards-based academic data will make it harder for districts to identify students for targeted supports to accelerate learning this summer or at the start of the new school year.

Summer and 2020-21 reopening planning has arrived and presents opportunity

As school systems close out this upended school year with virtual graduations and celebrations, we await more information on their next steps. What have they learned from this first, unexpected trial of remote learning? What do they believe is possible to accomplish next school year with similar uncertainty but more planning time? How will systems jump on opportunities in this moment to build new, better systems instead of restoring old, inequitable ones? What is possible for students in 2020-21?

We are just beginning to see their responses. Right now, just 47 of the 100 districts in our updated review offer summer school plans for elementary and middle school students, and 58 offer summer school for high schoolers. And most of those plans look like traditional summer school, focused on review or credit recovery, not new or innovative efforts to begin making up for the learning students likely lost this spring.

No district we reviewed has yet launched a comprehensive reopening plan, and just 22 percent have named a process or timeline for developing 2020-21 fall reopening plans. These planning processes will require involvement from state education agencies and state and local health agencies. And they depend on uncertain information and recently updated guidance from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, so we expect plans to mature over the coming weeks.

Districts have a chance to learn from missed opportunities and unanticipated challenges this spring. The question now is whether they will capitalize on it this summer.

Robin Lake is director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell. You can find her on Twitter @RbnLake. Bree Dusseault is practitioner-in-residence at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, supporting its analysis of district and charter responses to COVID-19. She previously served as executive director of Green Dot Public Schools Washington, executive director of pK-12 schools for Seattle Public Schools, a researcher at CRPE, and as a principal and teacher.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)