Weisberg: By Forcing Unions to Confront Some Deep-Seated Problems, Janus Loss Could Prove a Win for Them and Their Members

In siding against public-sector unions in the blockbuster Janus v. AFSCME case, the five Supreme Court justices in the majority argued that agency fees amount to forced endorsement of a union’s political agenda. I personally think the court was wrong to overturn the half-century-old precedent here; it’s a matter of basic fairness that teachers who reap the benefits of collective bargaining should also share in the costs.

Imagine, for example, if you demanded the right to withhold tax money from your local fire department just because you disagree with the mayor’s politics. You’d be laughed out of court. And if you weren’t, and you could withhold your taxes along with other dissenters, you’d thwart the rights of the majority who voted in the mayor.

It’s a moot point now, though. The unions lost. Among other things, this means the nation’s two largest teachers unions, the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers, face a new reality in which a large chunk of their annual revenue has transformed from guaranteed dues into optional contributions from members across the country. In her convincing dissenting opinion, Justice Elena Kagan forecast a dire, but realistic, future for public-sector unions in which “[e]mployees (including those who love the union) realize that they can get the same benefits even if they let their memberships expire. And as more and more stop paying dues, those left must take up the financial slack (and anyway, begin to feel like suckers) — so they too quit the union.” In theory, they could be staring at a budget hole big enough to cripple their operations.

But all the attention on this short-term financial challenge has obscured a blessing in disguise that could matter much more over the long run. Teachers unions are now forced to finally confront an existential threat that’s been brewing for years: They’re losing touch with more and more of their members.

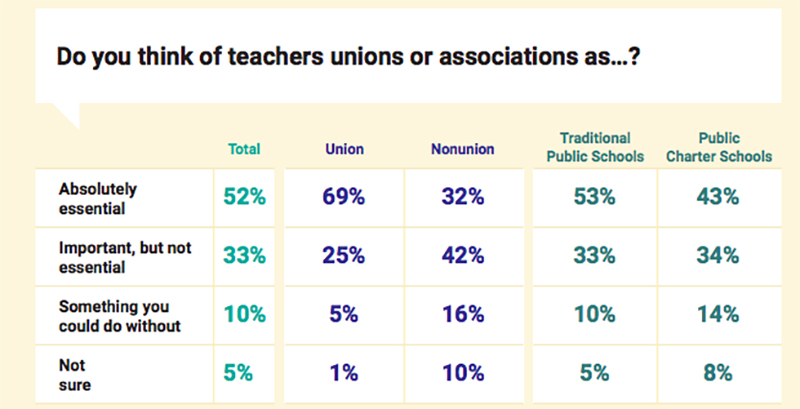

You don’t have to take my word for it. AFT President Randi Weingarten acknowledged this challenge in an op-ed over the weekend she co-authored with Educators for Excellence co-CEO Evan Stone (disclosure: I’m on the board of E4E). She pointed to results of a recent E4E survey showing that only about half of teachers view their union as “essential,” with 1 in 10 saying they “could do without” the union, 52 percent saying they felt unions represented their views only somewhat and 1 in 5 saying they didn’t feel they were represented in their union’s policy decisions at all, and about 40 percent saying they’d at least consider opting out of union membership or dues if given the choice.

You can see these statistics reflected in the declining unionization rates among teachers.

Many factors could be fueling teachers’ growing alienation from their unions. The past six months have shown that teachers no longer need to rely on union leadership to advocate for basics like higher salaries. The protests in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Arizona, and beyond were largely grassroots movements, organized largely with free tools like Facebook. The educators leading those charges often blew past the limits on negotiating positions and tactics that unions tried to set.

Our own research has long suggested that a significant number of teachers don’t want their hard-earned salaries going toward union-led defenses of incompetent or abusive colleagues.

Whatever the exact causes, this is a problem teachers unions would have needed to solve to survive, even without an immediate crisis created by the Supreme Court. After all, if the unions really do see millions of dollars disappear from their coffers in the months ahead, it will be because a significant number of their own members decided their union hasn’t earned a chunk of every paycheck.

The good news is that there are some practical steps teachers unions could take to both solve the short-term revenue gaps they might face post-Janus and win back the trust of their current members.

Right now, unions wear two hats. They’re collective bargaining agents, representing public school teachers in contract negotiations, grievances, and disciplinary cases. And they’re political advocates, speaking on behalf of their members in Washington and state capitals, and helping to elect handpicked candidates at all levels of government. With fewer resources, unions probably can’t afford to play both roles.

Unions could opt to greatly reduce their political activity and focus exclusively on collective bargaining, district by district — but this probably wouldn’t end well. Though they are often among the most powerful political forces in state capitals, they are already losing ground legislatively on a host of issues, from defined-benefit pensions to tenure. How effectively could they really negotiate on issues locally when many legislatures, freed from the unions’ political clout, would preempt or limit whatever victories they gain in collective bargaining?

The more radical move would be to get out of the collective bargaining business and become professional associations — think the American Medical Association or the Association of Trial Lawyers. It’s a role the National Education Association once played many decades ago. In that capacity, the NEA didn’t negotiate salaries and benefits, but it still made life better for millions of teachers by advocating for basic school funding during the Great Depression, the G.I. Bill after World War II, and civil rights legislation.

As professional associations, unions could put all their resources and political clout behind a long-term plan for elevating the teaching profession through higher pay, more rigorous performance standards, and better working conditions. They could support their members’ grassroots advocacy for this agenda without any obligation to defend individual members who engage in misconduct or who simply aren’t up to the job, a change that would probably win them new allies.

On a practical level, this may be the unions’ best chance to survive in a hostile political and legal climate that shows no signs of improving. But it’s not a surrender — far from it. It’s a path that would let unions reclaim control of their own fate and become a force for positive change in education. If union leaders have the courage to take it, we may look back a decade from now and see that teachers turned a short-term loss in Janus into a long-term win.

Daniel Weisberg is chief executive officer of TNTP.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)