As Union Membership Drops Among Teachers, Will Weaker States Survive Janus?

Union membership rates increased modestly across the entire U.S. economy in 2017, despite lagging numbers in the area where union market share is largest — the local government sector. A deeper dive into figures provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics reveals that teachers unions had a particularly bad year, losing two full percentage points in its share of America’s teaching force.

Unionization rates by job category are available at Unionstats.com, a database compiled by economists Barry Hirsch and David Macpherson. Although the numbers merge public- and private-sector teachers, they still provide a valuable overall look at the success of union recruitment efforts relative to the number of potential members.

Last year 44.9 percent of U.S. elementary and middle school teachers were union members, down from 46.9 percent in 2016. Secondary school teachers belonged to a union at a 50.2 percent rate, down from 52.3 percent, and special education teachers were union members at a 51 percent rate, down from 53.9 percent.

These rates provide a much-needed perspective to the debate over agency fees and the Janus v. AFSCME case, which will be heard by the Supreme Court in late February. Even under current law it is less than a 50–50 proposition that a teacher belongs to a union. Perhaps we ought to pay more attention to what non-members think and say about education, since they are the majority.

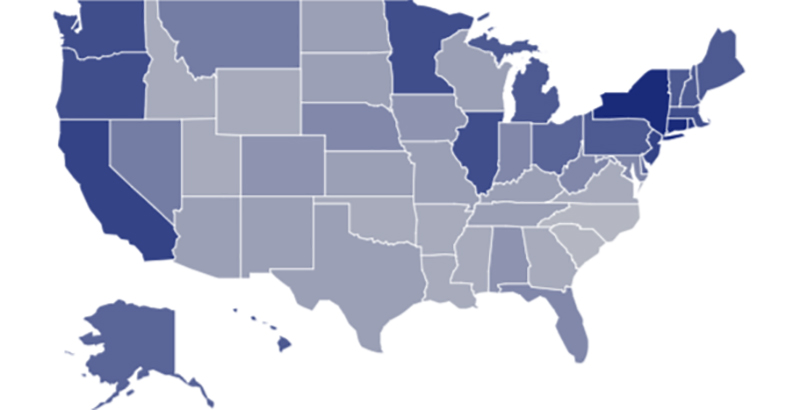

Hirsch and Macpherson also break down public sector unionization by state. I culled membership rates from their tables, and noted the change from 2016 to 2017.

The government workforce is more than 50 percent unionized in only 10 states. All are agency-fee states. Of course, many job categories — most management positions, for example — cannot be unionized, which makes 100 percent unionization unachievable. Unions themselves offer the best benchmark for how high rates can reach: 73.8 percent of their employees were unionized in 2017.

If agency fees were to be abolished, membership rates in the 22 agency-fee states would fall dramatically over time. The open question is how large of a trickle-down effect will occur in the other 28 states. Will they carry on as usual, or will they suffer from reduced financial and organizing support from their parent unions? The future health of the national public-sector labor movement may depend on whether it can avoid being divided into camps of haves and have-nots.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)