Virtual Standstill: When a Georgia Online School Tried to Fire For-Profit Operator K12, Students Were Locked Out of Their Computers

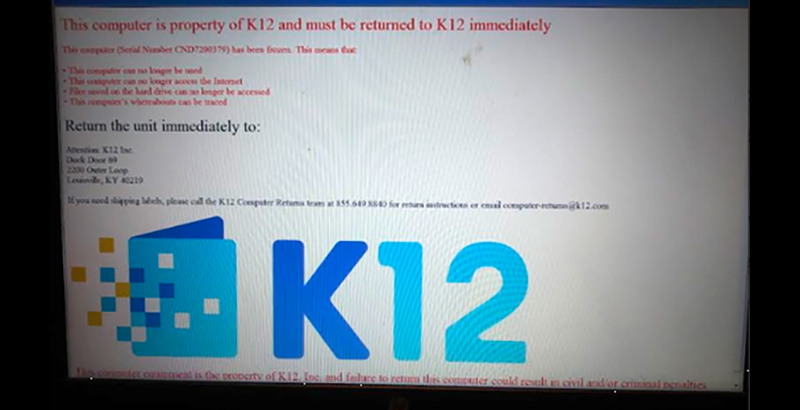

As the new school year approached, students at Georgia Cyber Academy — the largest public school in the state — fired up their school laptops to find a foreboding message.

“This computer has been frozen,” the red letters said. “This computer can no longer be used. This computer can no longer access the internet. Files saved on the hard drive can no longer be accessed. This computer’s whereabouts can be traced.”

The laptops, the message said, should be returned immediately to K12 Inc., the for-profit company that had run the school, providing everything from its teachers to its website, since its founding 12 years ago. A number to call for a shipping label was provided.

At an online-only school like GCA, students’ computers are the portal through which everything takes place — the door they open every day to gain access to their virtual classrooms. Unable to log in, they had no access to class materials, transcripts, health records or even term papers, emails and other personal files saved to their hard drives. Showing up and finding the computers locked, with no further explanation forthcoming, was baffling.

Equally frustrating, phone calls to the school and visits to its website didn’t yield reliable answers. Staff, too, found themselves unable to get into their emails or access student information — including class files and special ed kids’ individualized education programs.

Some families found their calls and clicks rerouted to K12 Inc., while others were able to see explanations and guidance offered by the school’s board.

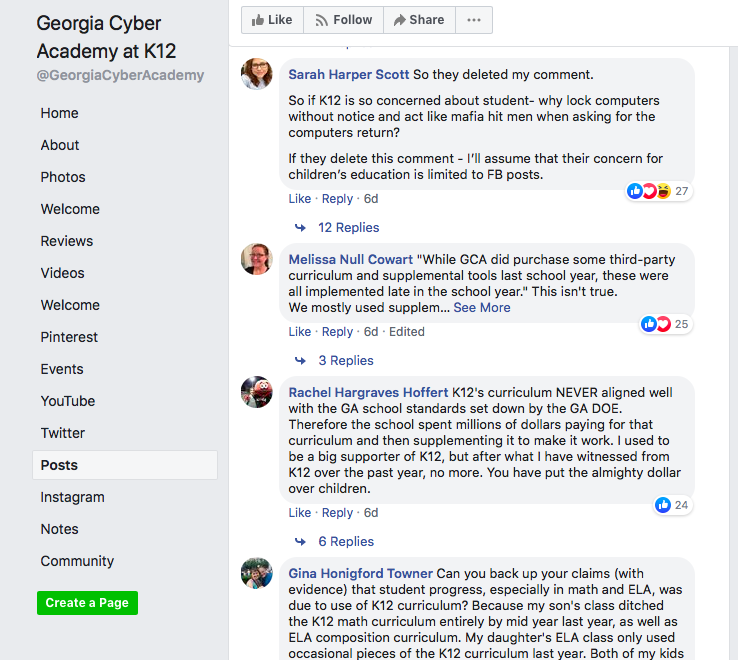

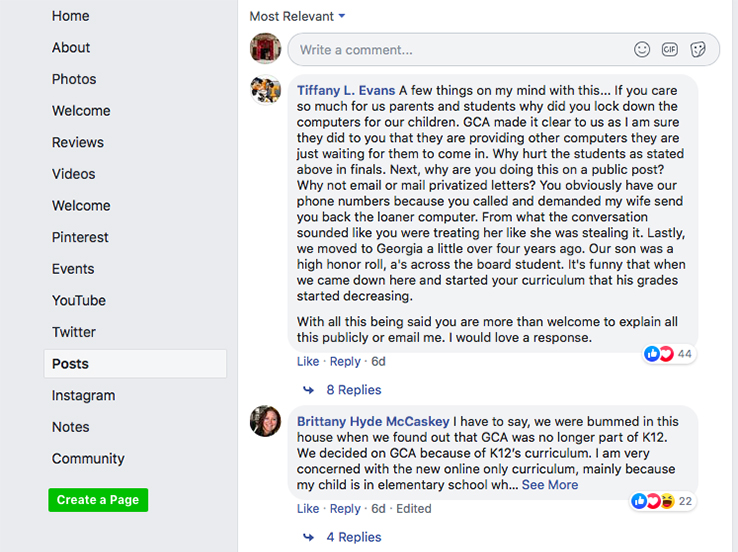

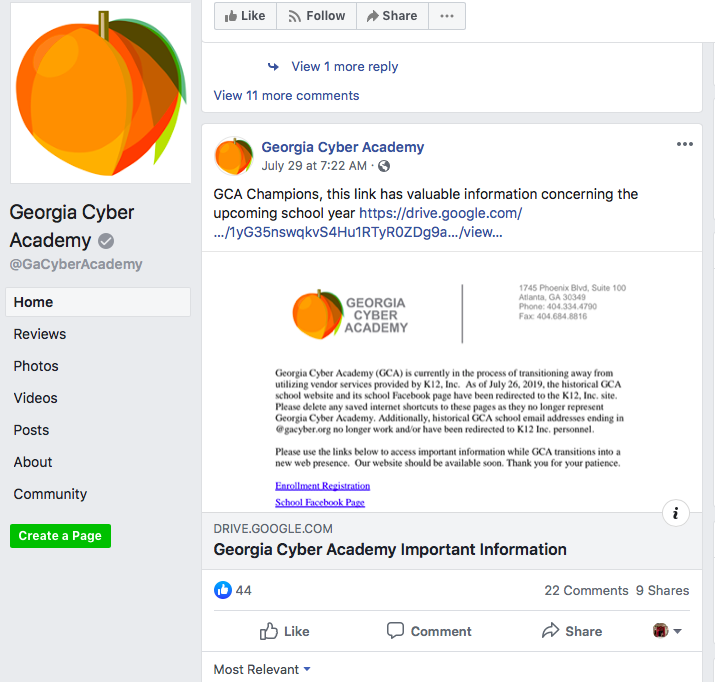

Parents complained about the chaos on two GCA Facebook pages — each graced with the school’s stylized peach logo — one controlled by the company, the other by the school. Many families wrote in comment threads about getting a hostile call from K12 demanding the computers’ return. Some said they were told their children were no longer enrolled.

The precise details of the breakup playing out beyond that locked digital schoolhouse door are in dispute. What’s certain is that over the past year, in an effort to respond to concerns about flagging academic performance, the school’s nonprofit board made a number of changes, culminating, in April, in a decision to terminate its contract with K12 Inc.

K12 fired back, accusing the board of breaching its contract. The dispute is in arbitration, a process that played out behind closed doors until the end of July, when the dueling narratives spilled out onto social media.

On July 30, the State Charter Schools Commission of Georgia, which oversees GCA’s charter, sent a letter to Kevin Chavous, K12’s president for academics, policy and schools, demanding that the company give GCA the school’s student and financial records by Aug. 2, the Friday before school was supposed to start.

The next day, as part of a separate process, the commission voted to table a K12 request to open a new school, Destinations Career Academy. Commission staff had recommended denying the request. A K12 attorney asked the panel to delay its decision so the company could address staff concerns.

The petition’s rejection — something that K12 executives acknowledged in a call with investors was a real possibility — would leave the virtual operator without a Georgia presence for the first time since 2007.

Later that day, Chavous posted a lengthy message on one of the Facebook pages, Georgia Cyber Academy at K12, asserting that the GCA board had overextended itself financially, among other “questionable” decisions.

The school year did, in fact, start on time the morning of Aug. 5, but the dispute between the school and K12 is far from resolved. Indeed, GCA staff started the year without access to basic information on their students, including health records and legally required special education plans.

K12 CEO and Board Chair Nate Davis confirmed to The 74 that the arbitrator ordered that the computers be turned back on for 30 days. The company, he added, will provide records, including the school’s financial accounts, once the school specifies what it’s looking for.

For his part, GCA Executive Director Mike Kooi said he can’t discuss the arbitration, but families are already receiving new computers. A news release from the school described K12’s actions as “purposeful, retaliatory, and wholly indefensible.”

The stakes are sky-high — both for GCA’s 11,000 students, and for ongoing efforts in Georgia and a number of other states to hold virtual schools accountable. The largest player in the booming online education sector, K12 Inc. manages schools that enroll more than a third of the 300,000 U.S. students who attend cyber schools.

GCA last year received $94 million in state and federal funding. According to Kooi, more than $54 million of that was paid to K12.

Nationwide, most online-only public charter schools are governed by nonprofit boards that hold their charters — their permission to operate — but are operated by for-profit vendors. K12 also provides curriculum to a number of schools it does not operate.

The industry is rife with controversy, not least about the schools’ overall dismal results. In 2015, the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University, better known as CREDO, found the schools to have an “overwhelming negative impact” on student growth. Full-time online students, researchers found, on average were the equivalent of 180 days behind their peers in traditional schools in math and 72 school days — almost half a year — behind their peers in reading.

As reported by The 74, efforts to close for-profit virtual charter schools or impose performance standards have met with pushback and political pressure. A 74 investigation earlier this year revealed that a K12-linked parent group went after charter school oversight officials in three states by accusing them of corruption after they sought tighter accountability.

Georgia was one of those states. In 2017, its charter school commission threatened to close GCA, which had been earning Ds and Fs on state school report cards, for poor academic performance. Georgia auditors had also questioned its enrollment, saying the school reported having more students than its records reflected.

In November 2017, in response to the commission’s concerns, GCA’s volunteer board hired an executive director who, unlike his predecessors, was not a K12 employee. An attorney, Mike Kooi has a long history in education policy, including stints in former Florida governor Jeb Bush’s education department and as the education policy chief for the Florida House of Representatives. Along with a new school leader, he reports to the board.

“I was hired to be the eyes and ears of the board in the school,” Kooi told The 74. “After the ’17-’18 school year, it became apparent some real changes were needed.”

Under the guidance of a new school leader who also reports to the board, GCA lowered class sizes, limited enrollment by grade level and stopped the practice of rolling admissions. Students who are behind academically must now attend live classes; teachers have tools for monitoring whether a pupil who is logged on during class is paying attention.

In the process of changing academic practices, Kooi said, staff realized that the curriculum both was not priced competitively and did not align with Georgia academic standards: “It was the results we had been getting — or not getting — using it.”

According to a June GCA presentation to the state commission, the school brought on a number of non-K12 curricula and classroom resources, instituted new instructional support and teacher training, increased student counseling and took over employment of all but 21 support staff. Attendance shot up and academic proficiency began to rise.

SCSC Performance Review Presentation 18 19 Georgia Cyber Academy (Text)

While acknowledging that the current school leader instituted a number of fruitful changes that ensured that instruction reflected the material that would be tested, K12 asserted in a memo provided to The 74 that “recent academic improvement at GCA can be directly tied to the continued usage of K12 curriculum” and said it had documented to the state that its materials were aligned.

The issue of curricular quality and alignment is a hot topic in education circles at the moment. State and school officials generally agree that students will not do well on standardized exams if the materials they are exposed to do not reflect the content they will be tested on or is of poor quality. Determining whether a curriculum is aligned to standards is one part of establishing its likely effectiveness.

In March 2018, the GCA board began terminating the school’s curriculum and operations contract with K12. By May, arbitration had begun. GCA’s position is that it complied with the termination provisions in the contract. K12 disagrees, saying an addendum to the contract signed in January of this year is valid until summer 2020.

In addition, the company believes it is owed money from the past school year and has the right to charge for a transition agreement.

Kooi insists the school has paid K12 the entire amount owed for last year.

Davis said that going forward, K12 would like to negotiate what it believes are the school’s contractual obligations. “I’m sorry the world has to see this food fight between us and GCA and its board,” he said.

As the start of the 2019-20 school year loomed, tensions exploded into the public arena. While GCA families struggled to parse the conflicting messages on the various Facebook pages and websites bearing the school’s name, emails received as part of a public records request filed by The 74 with the state commission show continual back-and-forth among attorneys about the release of the school’s records and the arbitrator’s Aug. 4 deadline for reactivating student laptops.

The computers were frozen, Davis told The 74, as part of a process triggered by GCA’s decision to pull students from the K12 platform. “That removes [student] IDs, which ends access,” he said. “They should have left the accounts up so parents have access.”

This, too, Kooi disputes: “The computer problems were triggered by GCA only to the extent that K12 acted in retaliation for the board’s prior actions in replacing K12’s curriculum due to its consistent failure to yield positive academic results and its exorbitant price,” he said.

Late the afternoon of Aug. 2, while an extension was being debated, Chavous posted another message to the company-controlled Facebook page. “While GCA has been telling you that they will not be using K12 curriculum, services or computers, the school is now unable to meet its basic responsibility to provide every family with a computer in order to start school on Monday,” he wrote.

“Therefore, in support of GCA families, K12 will be activating your computers so your student will be ready for the start of school.”

In the comment threads, parents reported various degrees of success getting their children’s computers restarted and frustration over personal school-related files that had somehow vanished. GCA administrators tried to reassure families that new computers were on the way.

On Aug. 7, while the GCA community was still sorting out its technical issues, K12 announced its annual results in a call with investors. According to an Education Week Market Brief account of the call, Davis said GCA “wasn’t really that profitable” and was “getting near break-even” in profitability.

“From an investor’s standpoint, we must conservatively assume that we will not serve GCA for the upcoming school year and our financials reflect that fact,” he said. “We also cannot assume that the new school we support will be in service immediately.”

Business, however, remained strong with new schools coming online in Texas, Florida and Missouri, he said, in addition to eight new career academies. K12 revenue topped $1 billion for the first time in fiscal year 2019, marking growth of almost 11 percent a year, “based on the managed public schools program.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)