FDA Authorizes Vaccines For Youth 12 & Up, But Schools Unlikely To Require Shots

Updated, May 11

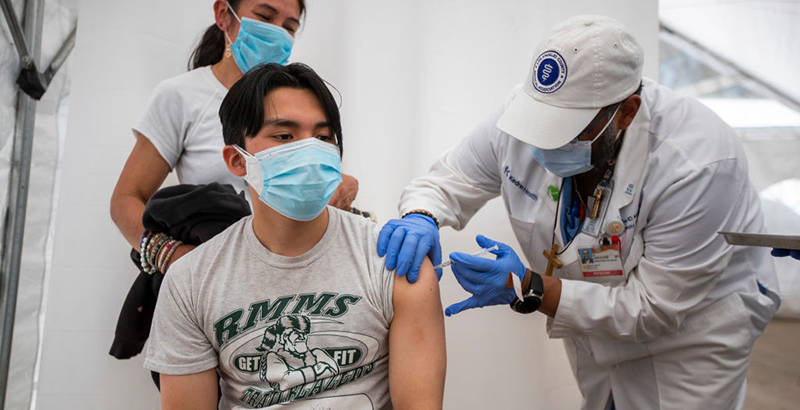

On May 10, the Food and Drug administration authorized use of the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine in youth aged 12 to 15. The vaccine manufacturers filed for full FDA approval for their shots May 7. A green light from the federal agency would remove a significant hurdle to school vaccine mandates, opening the possibility that states could add COVID-19 shots to their list of required vaccinations more quickly. Simultaneously, clinical trials for both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are underway for children aged 6 months to 11 years.

Adolescents were met with welcome news in late March when Pfizer announced that its coronavirus vaccine was 100 percent effective in preventing infection among youth aged 12 to 15 in clinical trials. Shortly thereafter, the pharmaceutical company requested authorization from the FDA to expand use to that age group, a process that typically takes several weeks for review.

That brings the timeline into focus for youth vaccinations: Kids 12 and up will likely be approved to receive COVID-19 shots sometime this summer, experts say.

But even if most middle and high schoolers become eligible for inoculation by the time the next school year starts, K-12 coronavirus vaccine mandates appear highly unlikely in the fall.

“We’re not talking about next year [for updates to school vaccine requirements],” Dorit Reiss, professor of law at UC Hastings College of the Law and a specialist in vaccine policy, told The 74.

That’s because the school vaccination requirements are dictated by state laws, and adding to that list involves an intricate — and often lengthy — policy dance between the federal and state government.

Over 30 colleges and universities have announced they will require COVID-19 shots before students can return to campus next fall, but public K-12 schools do not have the same latitude to enact such mandates.

Though public schools already require student vaccinations against diseases such as tetanus, measles and polio, there are a number of pivotal steps that coronavirus inoculations still must pass through before approval.

COVID-19 vaccines currently have Emergency Use Authorization status from the federal government, but the full clearance from the FDA may still remain months away. After that green light, shots must be recommended for children by a federal advisory committee and by the CDC before they can be added to schools’ lists of required vaccinations, Reiss explained.

“I think a lot of states will wait on full FDA approval to move on this,” she said. “No state has ever added a vaccine that wasn’t recommended and I don’t think they will.”

Lessons from polio

But even without the legal grounding to mandate youth vaccines this fall, schools may do well by serving as a hub for vaccination information and services, says Benjamin Linas, associate professor of epidemiology at Boston University.

As increasing shares of American adults gain immunity against COVID-19 through vaccines, children have begun to make up a larger portion of infections. Youth now account for 21 percent of new cases, according to a recent report and virus outbreaks have been documented even in elementary classrooms.

Linas envisions schools stepping up to help with vaccinations as they did over a half century ago during the polio epidemic.

“We offered the vaccine in schools to children, and parents across America eagerly signed their kids up,” Linas observes. “There are … lessons to be had from the polio experience.”

Sara Johnson, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Consortium for School-Based Public Health Solutions, agrees. She hopes schools will inform students and parents about the shots, she explained in an email to The 74.

“Schools can play a key role in educating their school community about the vaccine, providing information about vaccine access, answers to [frequently asked questions],” she said.

Too soon to drop masks

While those information campaigns are underway, middle and high schools will almost certainly be serving a mixture of vaccinated and unvaccinated students when kids return this fall. That means schools should hold off on dropping COVID-19 safety protocols, health experts say.

“Until you get upwards of 80 percent of children vaccinated, you’re going to have a hard time going back to pre-pandemic practices without some risk of illness and death,” Jeremy Kamil, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told The 74.

Even though COVID-19 cases have fallen from their mid-winter peak, safety appears to remain a key concern for many parents. Federal survey data show that large swaths of students remain remote well after their schools reopen for in-person learning. When high schools in Chicago reopened last week, buildings remained unusually empty — with as few as one student in some classrooms and many stay-at-home peers saying they were waiting to be vaccinated before coming back.

“We will still need masks in school in the fall,” said Linas.

Vaccine mandates possible in 2022

In the long term, mandating COVID-19 vaccines in school may still be a possibility.

Reiss, of UC Hastings College of Law, hopes that herd immunity might come faster in the U.S. than the complicated process of approving K-12 vaccination mandates, allowing schools to sidestep the issue completely.

“If we’re really lucky, adults will stop COVID enough that there’s not really a need for vaccine mandates for children,” she said.

While Reiss isn’t holding her breath — “We may not be that lucky,” she said — other experts believe COVID-19 can’t be defeated without inoculating kids. And the emerging possibility that vaccinations will require a booster shot within 12 months of the initial doses only heightens the likelihood that states will eventually need to create a policy addressing COVID-19 shot mandates for students.

Health experts, too, are mulling the possibility of school vaccination rules.

“We need to have a serious discussion about mandating COVID-19 vaccination in K-12 settings,” Philip Chan, associate professor of medicine at Brown University and medical director for the Rhode Island Department of Health, told The 74.

If officials do pursue this option, policies will likely differ from state to state, as they currently do for other mandated vaccinations. Some state laws allow opt-outs for religious and ideological reasons, while five — West Virginia, Mississippi, California, Maine and New York — allow no non-medical exemptions at all.

Any school-based mandates would likely afford additional flexibility to parents, predicts Reiss.

“You can imagine a state that doesn’t have a non-medical exemption will add the COVID vaccine, but will allow parents to get an exemption from just that one because it’s so new,” she explained.

In the face of widespread vaccine hesitancy, such leniency may concern some observers worried for community-wide immunity. Indeed, lax opt-out laws combined with a fervent anti-vaxxer movement in California led to record-breaking measles outbreaks at some Golden State schools in 2019.

But parents should not fret, says the law professor. Rather than having all people vaccinated, the key is simply having enough people vaccinated.

“A lot of people look at herd immunity and think it means that no germ will come in. That’s not how it works,” said Reiss. “If we have high enough rates of vaccination, those diseases can’t spread.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)