USC Expanding Civil Rights Research Hub on Former Campus of Historic Black School

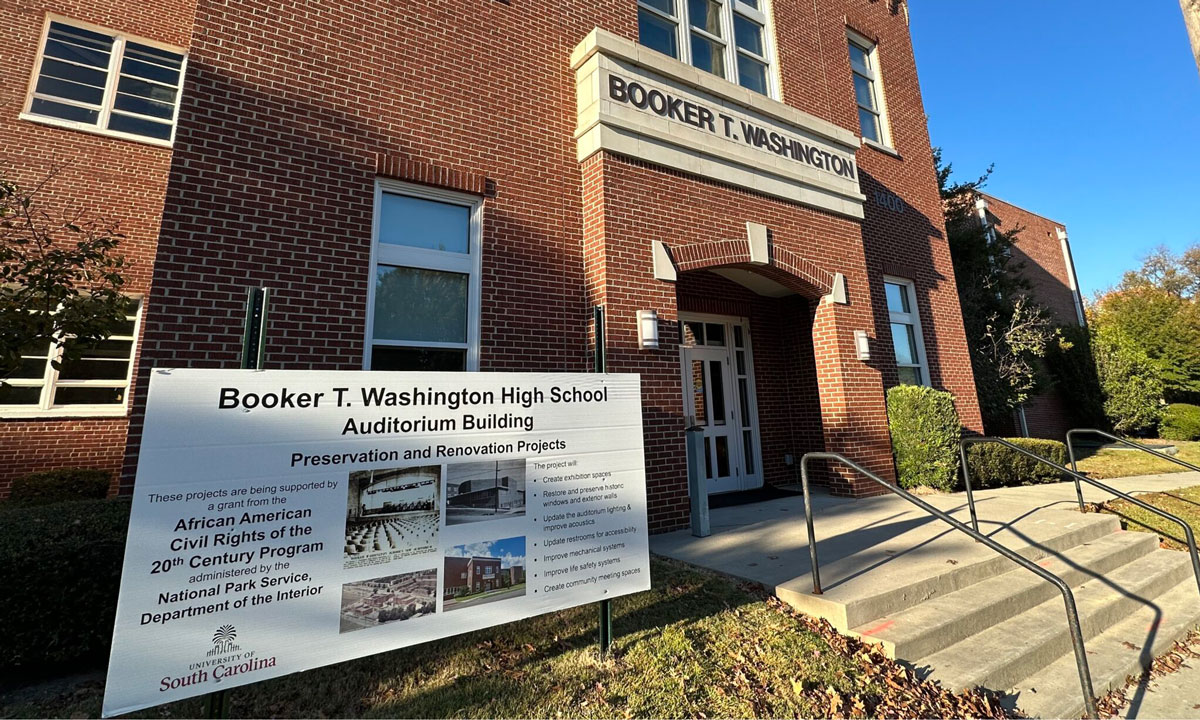

Plans call for new construction at Booker T. Washington High School campus in Columbia, a half-century after it was shut down.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

COLUMBIA — With restoration of what remains of Columbia’s first Black public high school fully funded, the director of the University of South Carolina’s civil rights center is turning his attention to expansion.

The estimated $24 million project involves new construction on the historic Booker T. Washington High School property. The stories and contributions of South Carolinians in the national Civil Rights Movement can be put on display in a second, modern building, said Bobby Donaldson, director of the University of South Carolina Center for Civil Rights History and Research.

Renovations at the former high school auditorium started a decade ago. It’s the only building left standing on the campus beloved by generations of Black Columbians.

The last phase of improvements is set to begin in late 2024 or early 2025. It’s funded by a $5 million federal grant awarded in June. That will bring the total spent on its preservation to $8.7 million.

But a high school building built in 1956 has its limitations.

“The new space is where we can envision how we reach audiences decades beyond our time,” Donaldson told the SC Daily Gazette.

Today, visitors will find walls full of informational placards about the history of the school, its students and the educators who once walked its halls. But there is no space to permanently house exhibits and the school’s collection of audio recordings, film clips, photographs, postcards, diaries and manuscripts. There have been temporary displays there.

Funding for the expansion

The new, adjacent facility will house a research library, archives, conference space, offices and modern exhibit space. Collections include the official papers of South Carolina senior Congressman Jim Clyburn, a Democrat first elected in 1992. The space will include more immersive, interactive and high-tech displays to “bring history to life,” Donaldson said.

So far, he’s raised $9 million for the expansion from a combination of federal grants, private donations, the university and most recently, $1 million in the state budget sponsored by state House Minority Leader Todd Rutherford, D-Columbia.

Donaldson hopes to use the state funding to encourage more private sources to chip in on the project.

“I want to give people a reason to come to Columbia,” Rutherford said. “I think if Columbia is going to be on the map, we have to take advantage of our assets. “The (Congaree) River is one of those and our history is another.”

The center’s new building will pay homage to the once 4-acre high school campus that was at the center of Columbia’s Black community from 1916 through its closure in 1974.

‘More than a school’

Long the largest Black public high school in the state and the only place Black children could receive a high school education in Columbia as southern states clung to segregation, Booker T. was a source of pride that shaped generations of educators, trades workers and community and Civil Rights leaders, Donaldson said.

Donaldson still remembers what Doris Glymph Greene told him when renovations began in 2013 thanks to a donation from another Booker T. graduate. Green was the school’s 1959 valedictorian and created the foundation dedicated to preserving its history.

“I want you to know this building is more than a school to us,” Donald recalls her saying. “It’s a shrine to the struggles and triumphs of African Americans in Columbia.”

Alumni, faculty and community leaders protested the school’s closure and sale to the University of South Carolina in 1974, to no avail. USC gradually swallowed up the property, bulldozing the classrooms and gymnasium to build dormitories for college students. It was only a decade earlier that the university admitted its first Black students since Reconstruction.

The school’s lone building standing is itself a testament to the struggle for equality.

It was built with collections from South Carolina’s inaugural 3% sales tax, which then-Gov. James Byrnes pushed as a way to thwart desegregation. Hundreds of Black- and white-only schools were built in a failed effort to prove public schools could be “separate but equal.”

The effort to expand the center comes on the tail of another milestone in the endeavor to acknowledge and amplify the stories of Black South Carolinians.

How it differs from other museums

The city of Charleston this summer celebrated the long-awaited opening of the $125 million International African American Museum, located on what was once the largest U.S. point of entry for enslaved Africans. The museum, two decades in the making, features exhibits on African culture dating to 300 B.C., the transatlantic slave trade, the Holy City’s role, and the little-known achievements of Black South Carolinians.

Donaldson said USC’s civil rights center works with museums, including IAAM and the Penn Center on Saint Helena island, home to the Gullah Geechee culture. But his work is less about tourism and more focused on archiving, researching and providing resources to educators who teach U.S. history, he said.

“What we aim to do with our work is to remind audiences that South Carolina played a valuable role in the long struggle for civil rights,” Donaldson said.

That history includes the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1963 decision, Edwards v. South Carolina, in which the high court ruled the state violated the First Amendment rights of Black high school and college students when police arrested them for protesting on the Statehouse grounds against segregation.

Then there was Sarah Mae Flemming, who protested segregation on Columbia’s city buses more than a year and a half before Rosa Parks’ refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

When Clyburn retires, researchers will be able to peruse his congressional papers as well as files from his 18 years as the South Carolina Human Affairs commissioner.

Rutherford said one trip to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., shows just how much of the Civil Rights Movement started in South Carolina.

Expanding the Center for Civil Rights History and Research, he said, provides the opportunity to educate the public right here in the Palmetto State.

SC Daily Gazette is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. SC Daily Gazette maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Seanna Adcox for questions: [email protected]. Follow SC Daily Gazette on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)