Urban Design Firm WXY Is at the Center of the Country’s Most Contentious School Integration Work — From New York City to Maryland. Who Are They, Exactly?

Updated, Feb. 26

A contentious process to promote school integration in Queens is moving forward after being temporarily derailed by parent protests, many targeting the firm contracted to lead what will likely be impassioned and complex community discussions around race and equity.

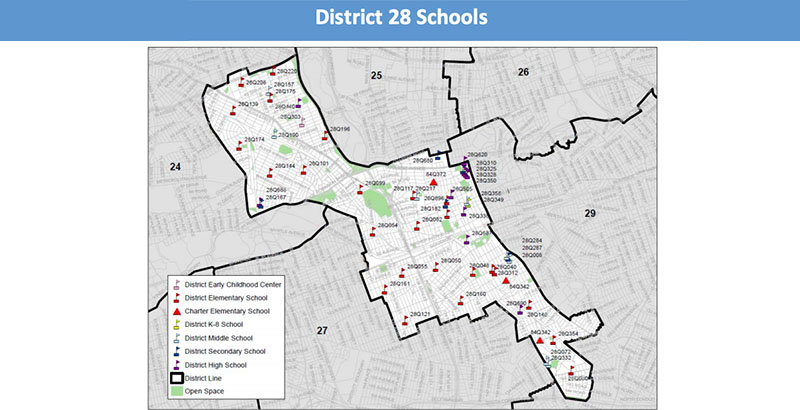

Although meetings for a potential diversity plan to integrate and share resources among District 28’s 13 middle schools are now slated to start next month, many parents are unhappy with how little they know about WXY Studio, a New York City-based architecture and urban design firm whose work has been at the center of high-profile school integration efforts around the country.

In Queens’s District 28, parents have questioned the scope of WXY’s contract, its strategy for reaching all communities, and how its past projects position it to spearhead discussions that could ultimately influence where their children attend school and learn.

“I thought architects built buildings,” parent Judy Wong, whose two children attend school in Rego Park, flatly observed at a District 28 Community Education Council meeting earlier this month. “I don’t know if [WXY] would be qualified to do — whatever this is.”

The firm’s role — facilitating wide-reaching community engagement that informs and guides future recommendations for achieving equity and diversity in schools — is a recurring part of its portfolio. And this is not the first time WXY’s motives, methods and qualifications have become fair game in the conflicts around school desegregation efforts.

WXY oversaw a similar process two years ago in Brooklyn’s District 15, though parents and community members had advocated for that undertaking at the onset, and is conducting a controversial review of school boundary lines in Montgomery County, Maryland, that has raised parents’ ire. It’s simultaneously collaborating with the School District of Lancaster in south-central Pennsylvania to propose new school boundaries. Nearly a decade ago, it also evaluated prospective school assignment policies in Boston Public Schools, a city whose history is inextricably tied to school segregation battles.

“WXY does important work to bring voices together, and does not make any decisions about the plan that will come out of this [District 28] process,” a New York City Department of Education spokeswoman said in a Feb. 14 email.

That WXY will not steer public dialogue toward a preset conclusion has been underscored repeatedly by city school officials, who earlier this month delayed scheduling public talks for District 28’s diversity plan after parents decried a lack of transparency around decision-making and who had a seat at the table.

So far, “we don’t get any feedback from WXY … It’s not clear how they’re planning to go through the whole process,” said Forest Hills resident and parent Art Raevsky, who also attended this month’s Community Education Council meeting. “It leads us to believe that something is going on behind the scenes, that there’s some predetermined outcome.”

In what appeared to be a concession, the DOE last week announced that it had extended the project’s timetable from June to December, promising meetings at every local elementary and middle school beginning in March along with six public workshops starting in May. Parents will receive at least three weeks’ notice for each workshop date.

The DOE also released the sought-after names of the 20 current “working group” members who will ultimately use community feedback to submit recommendations to the DOE, with the goal of increasing middle school diversity and boosting students’ academic achievement. The members include students, teachers, PTA presidents and leaders of local multicultural associations. Officials say the list will expand.

“We are excited to make this process more inclusive,” the DOE’s announcement read. Its success “is dependent on hearing viewpoints from every corner of the District, mutual trust, transparency and clarity.”

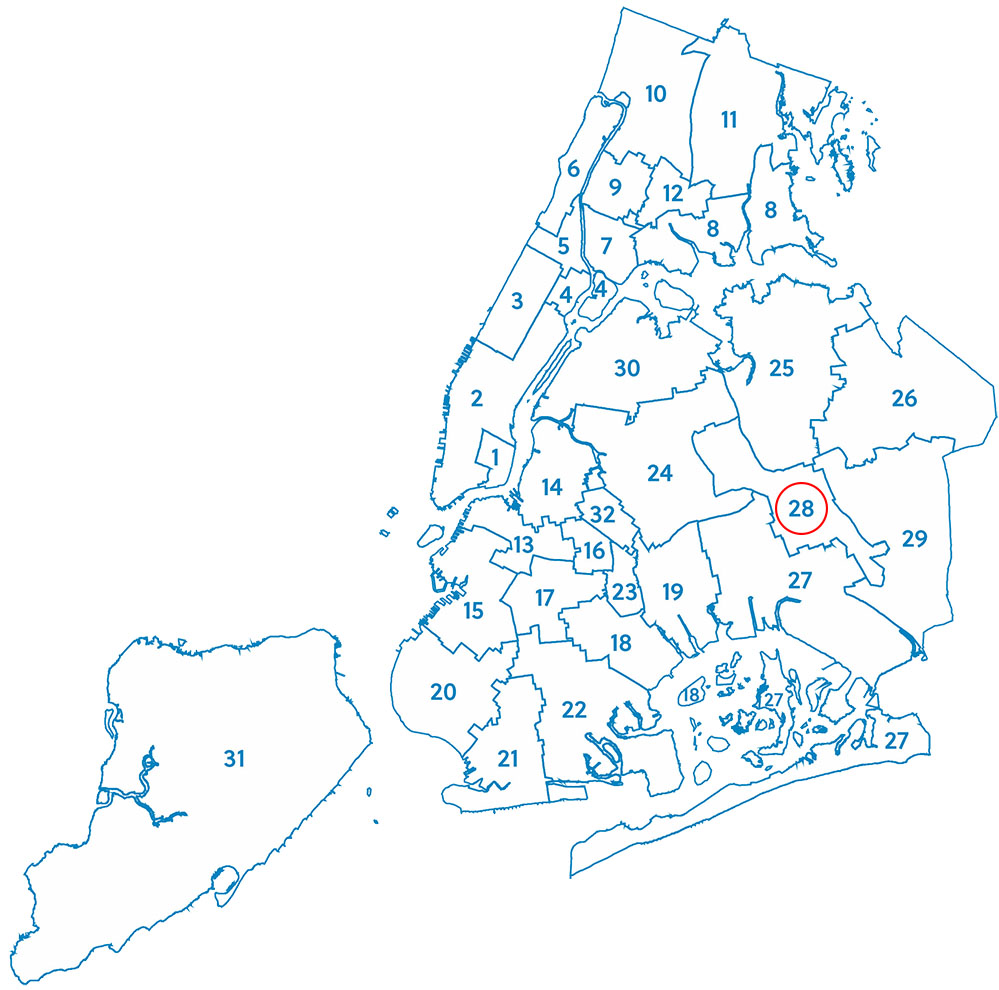

Far-flung District 28 is slender and long, nearly touching the outer rim of the behemoth NYC system and stretching from Forest Hills to Kew Gardens, Rego Park and Jamaica. It is whiter and more affluent to the north, and more racially diverse and working-class to the south. Not a single District 28 middle school reflects the local demographics.

The DOE and WXY “use that word ‘diversity’ very loosely,” remarked Terri Wright, a Jamaica resident and mom of a 14-year-old boy. “I just want the same opportunity all around. Not ‘let’s give this side this opportunity’ or ‘let’s give this side that’ — it should be the same all over, whether north, south, east or west.”

Parents opposing a diversity plan in District 28 have repeatedly maintained that it would lead to rezoning and busing. The DOE in its letter to community members Wednesday re-emphasized that “there are no pre-determined outcomes” and that “recommendations can cover solutions including school resources, parent empowerment, student voice, and admissions policies.”

WXY declined to discuss past projects or its District 28 engagement strategy, but it provided a brief statement noting the challenges of school diversity work and its own qualifications.

“This is a new model for trying to solve a very, very complex issue that relates to lots of other things outside of education policy,” a WXY spokesperson said. “It requires a pretty unique set of skills, and I think we bring those to the table.”

‘A think tank that builds’

WXY, whose offices are in Lower Manhattan, was founded in 1998 and now employs some 50 people. The firm, which describes itself as a “think tank that builds,” has racked up numerous architecture and urban design awards. It was named one of the “World’s Most Innovative” architecture firms by business magazine Fast Company last year and received an “Excellence in Design” award in June from Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration for co-designing an affordable housing development in the Bronx for low-income and previously homeless New Yorkers.

The bulk of its clients are government entities — school districts fall under that umbrella — along with nonprofits.

Most of its experience is outside of education. Its website lists projects ranging from land use master plans to the design of sustainable energy infrastructure and pedestrian bridges. A fairly consistent thread across its portfolio, though, is gathering public feedback on thorny civic issues in traditionally hard-to-reach communities.

Akina Younge, the WXY project manager overseeing District 28 planning, has a master’s in public policy and a background in New York City and state advocacy efforts, including coordinating a campaign that won a first-ever rent freeze on rent-stabilized city apartments five years ago. Adam Lubinsky, a WXY managing principal also closely involved in District 28, wrote his Ph.D. at University College London on the impacts of school choice policies on cities.

WXY has collaborated with at least four school districts, including Boston’s, which like New York City grapples with highly segregated schools. The firm evaluated alternative options to Boston’s school assignment policy in 2012, though it didn’t make recommendations (the policy the district ended up implementing, which was meant to increase students’ access to good schools close to home, generated mixed outcomes).

When contacted about WXY’s performance, a Boston Public Schools spokesman replied that “those most intimately involved with this project are no longer with the district.” The 74 separately located a former Boston school administrator who was involved in WXY’s work, but he declined to talk about it.

In New York City, WXY is currently contracted to work with five local districts on their diversity plans — District 9 in the Bronx, Districts 13 and 16 in Brooklyn, District 28 and District 31 on Staten Island — at $155,000 each, or $775,000 total. District 31, though, is not currently utilizing WXY or any outside firm’s services, according to the DOE. The department would only say that WXY was tapped “following a competitive evaluation and selection process” when asked who else applied for the job.

WXY’s contract covers 1,105 “labor hours” for each local district, according to Panel for Educational Policy documents. With District 28’s timetable extended from June to December, the DOE acknowledged Thursday that “we’re assessing if there are any needed contract changes,” though it didn’t answer questions about additional costs.

As of early December, there wasn’t a locatable contract between WXY and the education department, according to a DOE officer’s response to a public records request filed by CBS. The response further stated that WXY did have a contract with the NYC Economic Development Corporation and that the DOE had “accessed the services of WXY Studio” through that contract. The city comptroller’s office, when contacted by The 74, said it was under the same impression. Asked about the discrepancy, a DOE spokeswoman said Friday that the contract with the Economic Development Corporation is “old” and not the D28 and WXY contract, which DOE holds.

The 74 in late January submitted a FOIL request for any contracts between the Economic Development Corporation and WXY, and is awaiting a response.

Shifting segregation in Brooklyn

Often armed with more questions than answers, some parents have theorized that the DOE and WXY will use District 15’s 2018 diversity plan as a blueprint, even though the districts are different in size, demographics and enrollment practices. The DOE has touted District 15’s plan — which opted to eliminate middle school admissions screens in favor of a lottery system that gives preference to English learners, low-income students and homeless students — as a success, with the change already shifting racial compositions at the local middle schools.

There have been mixed opinions on how WXY’s community engagement model played out in the Brooklyn district that covers Carroll Gardens, Park Slope, Windsor Terrace and parts of Boerum Hill and Fort Greene. Miriam Nunberg, a cofounder of advocacy group D15 Parents for Middle School Equity and a working group member, recalled being skeptical initially about the actual influence community members would have over the final plan. Her doubts largely revolved around the DOE and “what really would come out of this — whether this was going to be more window-dressing.”

It was reassuring that WXY “seemed disconnected” from the education department and was intent on establishing a diverse working group, she said. Though it took an extra two months to finalize the group’s 18 members, Nunberg was impressed with the team of students, parents, teachers, advocates, community leaders and others that materialized.

“It was a really nice balance” of people, she said. Nunberg added that “there were Spanish interpreters for every single meeting. We had headsets, so it was a real-time translation. … There was a very, very intentional effort to make sure that [all] voices were equally heard.”

Those members’ identities weren’t formally released until the final plan’s unveiling in late July 2018. Even with District 28’s working group members now named, some still take issue with their selection being made by WXY and the DOE, rather than parents and community members.

Other stakeholders were more critical of WXY’s outreach. Voces Ciudadanas, a nonprofit based in Sunset Park that seeks to empower low-income communities of color, declined to participate in District 15’s working group. It referred The 74 to comments it made in late 2017 — that it didn’t think there was a plan “to integrate marginalized communities in a meaningful and sustained way” or to address “deep rooted causes” of school segregation, such as “racial discrimination, economic neglect, [and] housing and real estate segregation.”

“The critiques are still valid today and in retrospect, they played out with the major players being the major players,” a representative for Voces Ciudadanas wrote in an email on the group’s behalf. “Families of color … were not centered in the process.”

Viewed as an outsider by some in Maryland

Concerns with transparency and inclusion have also accompanied WXY’s relationship with Montgomery County Public Schools, a diverse 165,000-student suburban district outside Washington, D.C.

“Nobody knows what [WXY] is,” district parent Anil Chaudhry said.

The firm last year beat out one other contractor, Cooperative Strategies, LLC, to conduct a nearly year-long school boundary review of the Maryland district for about $475,000. The country’s 14th-largest school system is facing overcrowding and rising enrollment projections, and its Board of Education wanted a comprehensive assessment of how current boundaries are affecting students’ access to schools that are diverse, not over capacity and within walking distance of home.

The firm is coordinating community workshops and meetings as part of its review. Contrary to many parents’ deep-seated concerns that the study will spark widespread rezoning and busing, the district has emphasized that WXY’s final report expected in June won’t include recommendations or policy changes.

While district officials “did pause when we realized this wasn’t the thing that they do 24/7,” Montgomery County schools’ chief communications officer Derek Turner said WXY won them over with its “creativity” and how it “had a better sense of our community and our community needs.” Officials seemed particularly excited about WXY’s plans to use all of its data analyses to create an interactive map that would allow users to fiddle with certain factors, like how crowded a school is, to see how changing that would alter other factors, like student diversity.

“This is an area where everything is evolving very quickly,” district superintendent Jack Smith told The 74. “As we think about the integration of data and information and engagement with the community … we really wanted to think about a very different, more interactive, more ‘push-in to the community’ kind of engagement than we’ve ever done before.”

WXY had coordinated six regional meetings in Montgomery County, reaching some 2,500 people as of Feb. 12, each time polling attendees to gauge which groups are underrepresented, Turner said.

Some parent groups, like One Montgomery, have publicly backed the school boundary review WXY is conducting, noting that it will provide “an independent, data-driven look” at how schools are being used, and how to reduce segregation. Many parents, though — often in posts on Facebook groups — say they feel the school boundary review has been largely out of public view.

“When we see an outside consultant coming in, that causes us concern, because we know that when parents want information about the process … the odds are pretty good we’re going to be given roadblocks,” said Janis Sartucci of the Parents’ Coalition of Montgomery County.

Chaudhry, who has three children in the district, attended one of the regional meetings and was troubled that he couldn’t get answers to what he deemed “two simple questions.”

“I said, ‘Can I get a clear definition that’s been approved by [the district] for words you’re using in this study? [Words like] equity … how do you calculate equity? Where’s the formula?'” he said. “The second question was, ‘Will the public taxpayer be able to see the underlying models and algorithms you used to get to your findings?’ I could not get an answer on that either.”

Chaudhry said his frustration is part of what inspired him to run for a Board of Education seat to ensure accountability moving forward.

“It starts with the Board of Education as the policymakers,” he said. But “now that WXY has committed to taking on this process, the ball is in their court. They’re getting paid $475,000 to do something; they should be able to clearly explain to the taxpayer what they are spending the $475,000 on, and what we expect to see in return.”

Turner, the district spokesman, said he believes that public discontent with WXY is likely misdirected.

“It’s not the vendor,” he said. “It’s that they have anxiety about the process.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)