As Universal Pre-K Struggles to Secure a Nationwide Platform, It Finds Hope in Cities Like Chicago

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s framework for an ambitious universal pre-K program in his city is the latest in a widespread national push for high-quality early education that is being driven at the local level.

Emanuel, who’s been trying to overhaul early education for five years, intends to provide free, full-day pre-K to all of the city’s 4-year-olds — an estimated 24,000 kids — over the next four years. The phase-in will start this fall with roughly 3,700 students whose families make about $46,000 or less a year.

Early education “is so essential for kids,” Emanuel said in a May 30 announcement. “You cannot make up those lost years if you don’t do it right. It should not be based on means.” Chicago pre-K currently operates on a sliding scale, with the middle and upper classes paying up to $14,000 per child annually.

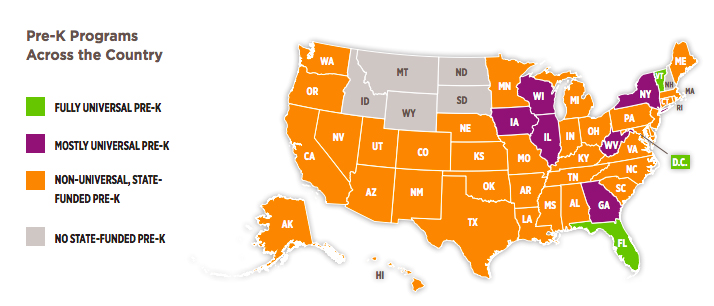

If the plan reaches fruition, Chicago would join cities such as New York, Washington, D.C., and Boston, which are spearheading large-scale pre-K initiatives amid uneven state progress and a growing arsenal of research touting the benefits of early education. While 43 states currently offer some form of state-funded preschool for more than 1.5 million children, only a handful can be accurately described as “universal.” Universal pre-K is free and open to everyone, regardless of socioeconomic status.

The benefit of a localized education system is that “we don’t have to wait until everyone wants to [progress] to move forward,” Steve Barnett, director of the National Institute for Early Education Research, told The 74.

A groundswell of support for pre-K

Eighty-two percent of Republicans and 97 percent of Democrats support making quality early education more affordable, according to a 2017 poll by the First Five Years Fund, an advocacy organization. And 79 percent want to see President Donald Trump and Congress work together to advance that agenda.

Bipartisan backing for state-funded pre-K — universal or not — has strengthened in recent years as research has affirmed the cognitive and social benefits of quality early education instruction.

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, a study of 4,000 students linked going to preschool with more honors course enrollments eight years later, along with a 7 percent drop in grade retention. Additional studies credit pre-K with kindergarten preparedness, increased high school graduation rates, fewer crimes, and a projected $8.90 return for every $1 invested in preschoolers’ education by 2050.

“You can talk to any kindergarten teacher, and they will tell you they know the kids who have had preschool and those kids who haven’t,” Simon Workman, Center for American Progress’s associate director of early childhood policy, told The 74. “They come to kindergarten ready to learn.”

But many state-funded pre-K programs leave some children out. More than half of state programs are “targeted” and prioritize lower-income kids, who often face substantial education gaps. Illinois’s program, for example, targets students with at least two “risk factors,” such as low income and a history of family neglect. In such states, middle- and upper-class families who are not eligible for state programs can pay thousands of out-of-pocket dollars for private providers.

Research also indicates that state-funded pre-K programs, especially when targeted, can be subpar — a “leaky bucket,” if you ask Barnett. During the 2016-17 school year, nearly 600,000 children (about 39 percent of total enrollment) were in state pre-K programs that met fewer than half of the national early education institute’s quality benchmarks. These benchmarks include a 20-student-maximum class size, a staff-child ratio of 1 to 10 or better, and a requirement for pre-K teachers to earn bachelor’s degrees. The last recommendation, however, is controversial.

This is where universal pre-K, with its high-quality, “free for all” mantra, becomes appealing — not just for early education advocates, but for politicians, ranging from former president Barack Obama, a Democrat, to conservative Georgia governor Nathan Deal.

A program that’s open to all children attracts more abundant resources because “everyone has a stake in the program,” Barnett said. And these higher standards, the institute reported, equate to a greater likelihood of closing the kindergarten achievement gap. As it stands, African-American and Hispanic children range from nine to 10 months behind in math and seven to 12 months behind in reading when they start kindergarten.

“If you think about how the system as a whole responds — if everybody in kindergarten had the benefit of preschool, it’s different teaching that kindergarten [class] than if only some of the kids did,” he said.

Cities take the lead

New York City, under the leadership of Mayor Bill de Blasio, pumped $300 million into its “Pre-K for All” initiative in 2014, more than tripling the number of 4-year-olds enrolled within two years.

Washington, D.C., developed a lauded pre-K program that serves a higher percentage of preschoolers than any state — 88 percent of 4-year-olds and 66 percent of 3-year-olds — and uses a comprehensive curriculum aligned to K-3 instruction.

And Boston, which, like Chicago, is pursuing universal pre-K, requires preschool teachers with bachelor’s degrees to obtain their master’s or additional certification in five years. It’s also building a formal partnership between private providers and public schools to expand families’ options.

With states differing in approach and levels of urgency, these localized initiatives have become models for pre-K expansion. Of the 43 states that fund pre-K, only a handful of them — including Florida, Vermont, and Wisconsin — have programs widely considered to be universal. State by state, the percentage of enrolled 4-year-olds fluctuates from less than 10 percent to nearly 80 percent, and more than half of state programs don’t operate on a full-day schedule. The federal outlook is even less promising after Obama’s call in 2013 for a comprehensive pre-K federal-state partnership program failed.

One of the benefits of being trailblazers, Workman said, is that cities can tailor the plans and subsequent rollout to their individual needs and financial realities.

In Chicago, more than three-quarters of the school district’s children are economically disadvantaged, spurring the immediate focus on high-need families. Proposed funding for the program would come from additional allocations in last year’s budget overhaul, block grant funding, and this year’s Chicago Public Schools budget, which is expected to go to a vote at the end of July. The program’s cost, starting at $20 million this year, is slated to reach $175 million annually by 2021.

“New York City did it very quickly, straight away,” Workman said. “But it depends on what resources you have. … One of the things I like about Chicago’s plan is having the phase-in. It kind of allows you to say, ‘OK, let’s first start with the highest-need areas,’ but then let’s not just say, ‘That’s all.’ Let’s move it forward.”

And while turnover in local government can pose a risk to these initiatives’ sustainability, early education’s mounting popularity is keeping Bruce Atchison, early learning director at the Education Commission of the States, optimistic that universal programs like Chicago’s will make it to the finish line. That optimism could prove useful in Chicago, where Emanuel is facing a crowded mayoral race in 2019 that’s become increasingly complicated by a district sex abuse scandal.

“Who the mayor is, who the city council is … it can all turn over in a heartbeat,” he said. “Hopefully … this is a program that would be sustainable solely based on the fact that it’s benefiting those children.”

The varying approaches at the state and city level, though, have made it difficult to paint a consistent picture of what universal pre-K entails, experts said. How many hours a day should young children attend? What should teacher degree requirements be? Where does the funding come from?

Having a universal program also doesn’t necessarily mean every child gets a spot. It means each is eligible for one. There are often applications and waiting lists, including in New York City and D.C.

That’s why there ultimately needs to be a uniform effort at all levels to develop a true, nationwide universal pre-K system, said Louisa Diffey, policy researcher at the Education Commission of the States.

“A combination of the local and state desire, and then the national will” would make it successful, she said. “It’s a trifecta that’s necessary.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)