Three Distinct Charter Schools, One Shared Mission: To Provide High-Quality Choices for Students in Rural Idaho

Caldwell, Idaho

At 17, he’s old to be a high school sophomore, but academically, Axel lags far behind his classmates.

School for him has been a series of frustrations and disappointments. Axel, who asked that his last name not be used for privacy reasons, has been kicked out of several schools, and more than once he’s come close to dropping out.

Because Axel struggles to read, traditional classes don’t engage him. Sitting in class trying to focus seems like a waste of time. He loves working with his hands, and that’s what he’d rather be doing.

But now, enrolled in a new career and technical education public charter school in this town of about 55,000 people 30 miles west of Boise, he’s feeling hopeful about school for the first time he can remember.

In his previous schools, Axel was denied access to his favorite classes — electives — because he was so far behind in his core academic subjects. “At Caldwell High, they kept me out of the auto shop because they wanted me to focus on my math and English skills,” he said. “They gave me extra English and math. I told them I don’t like pencil-and-paper work, but they didn’t listen.”

At Elevate Academy, school leaders Matt Strong and Monica White, longtime administrators in the Caldwell School District who quit their jobs to launch a charter school, have created a model that allows students to apply core academic concepts to hands-on learning.

“We are going to adjust Axel’s schedule so that he is living out in the shops,” Strong said. “And we’ll hire a reading specialist to help him with his reading skills.”

Strong is confident that Elevate Academy, which when fully enrolled in 2021 will serve 460 students in grades 6-12, can get the Axels of the world through high school and on the path to gainful employment and productive citizenry.

The school opened in August 2019, and it illustrates how different school models, especially when spread into areas often short on educational options, can be a life-changer for some traditionally underserved students.

Elevate Academy is one of three starkly different public charter schools that opened this year in rural areas of southwestern Idaho. The other two schools are Forge International in Middleton, a K-12 International Baccalaureate school, and Treasure Valley Classical Academy, a K-12 school in rural Fruitland with a rigorous, Great Books-inspired curriculum.

The three schools have benefited from technical and financial assistance from Bluum, an Idaho-based nonprofit that recruits and trains new leaders for new schools, be they public, public charter or private. The leaders of both Elevate and Treasure Valley Classical Academy received year-long Idaho New School Fellowships to plan and launch their schools. The schools have also received substantial grant funding from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation and facility funding support from Building Hope.

While adding these three new choices to the Idaho education mix has enriched opportunities for students, all three schools faced adversity and opposition as they worked to open this year. In some cases, local school districts fought against the schools opening, saying they would duplicate services already in place and drain resources from cash-strapped district schools. Construction delays (Idaho is one of the nation’s fastest-growing states) also hampered the two new school buildings, Forge and Elevate. And renovations to the classical academy’s historic downtown Fruitland school building forced a week’s delay in the school’s opening.

Nevertheless, the three new schools illustrate that, in Idaho at least, the charter school sector continues to grow, evolve and serve a diverse group of students. And despite the opposition from predictable quarters, all three schools have won widespread community support.

Elevate Academy

Giving at-risk students in-demand workplace skills

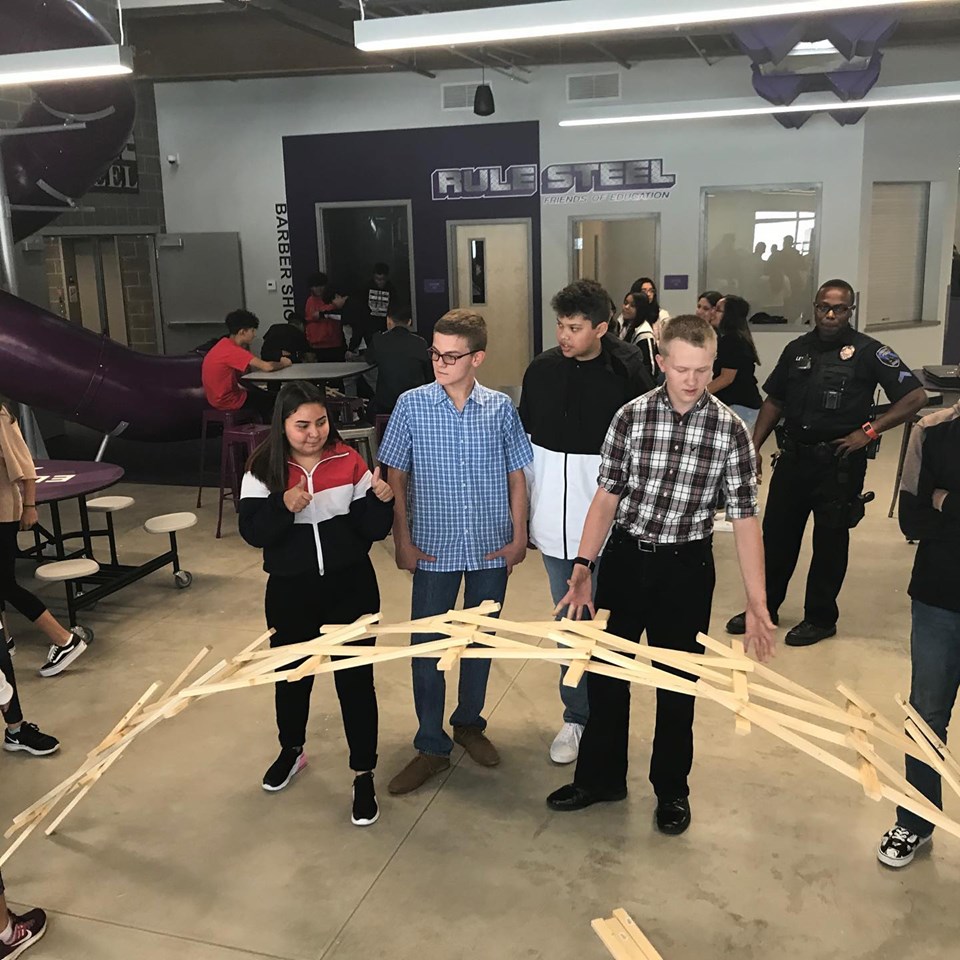

Elevate Academy offers students core academics as well as opportunities to specialize in welding and manufacturing, construction management, culinary arts, graphic arts, health professions (nursing), criminal justice, firefighting (land and structure) and business/marketing. Set apart from the new classroom building, a cavernous shop is stocked with state-of-the-art equipment, where students will spend major chunks of their days developing in-demand workplace skills and habits.

The student body is 100 percent at-risk by Idaho’s definition of the term. That means meeting at least three of 13 state-set criteria, including low GPA, high absenteeism, serious medical or personal issues, involvement in the judicial system, or being a parent or pregnant. The school is 90 percent free and reduced-priced lunch, with 79 percent of students identifying themselves as Hispanic or Latino. About 1 in 5 students have an Individualized Education Program (IEP) that they brought to Elevate from their previous schools.

Elevate is a mastery-based school with students progressing through their studies at their own pace unbounded by traditional seat-time requirements. Scheduling at Elevate reflects this mastery approach; it is one of the school’s unique features. Students are responsible for setting their own schedules, which change every day based on their individual needs and interests. The idea, White said, is to teach students self-regulation, an essential, basic workplace skill that many students — and high school graduates — lack.

“There are no bells. They have to move when it’s time for them to move according to their schedule,” White said. While this has been tough on kids and teachers alike, especially in the early weeks of school, “we’ll get there, even if it’s in baby steps.”

Like Axel, many Elevate students struggled in their previous schools. Others, however, were high achievers. Based on assessments of the first group of Elevate students given in September, students ranged from the first to the 93rd percentile, though 70 percent reside in the bottom quartile.

One might think that a school district would welcome with open arms a school eager to take some of its most challenging students off its hands. But that hasn’t been the case in Caldwell.

In June 2018, when White and Strong presented their charter application to the Idaho Public Charter School Commission, the Caldwell School District Board of Trustees and superintendent voiced full-throated opposition to their school.

“… We have serious concerns about the impact that another alternative school would have on our district and our community,” the board wrote in a June 5 letter to the commission. Elevate, the board continued, would be “an unnecessary expense to the tax payers [sic] of Idaho,” because its offered services would amount to a “duplication of services already provided” by Caldwell and neighboring districts.

The school “will not only divide community partners and resources, but will put additional strain on our ability to recruit highly-qualified educators for these already identified ‘hard-to-fill’ positions,” the trustees’ letter said.

Despite the district opposition, the charter commission voted unanimously to grant Elevate’s charter.

District pushback was unfortunate but predictable, said Greg Burkhart, president of Rule Steel, a Caldwell steel fabrication company that partners closely with Elevate Academy. Some traditional educators, whether consciously or not, look down on educational approaches that aren’t geared to sending kids to four-year colleges, he said.

“Unfortunately, people in systems sometimes forget that times change,” Burkhart said. “They don’t take time to think that maybe the way we’re doing this isn’t working for all kids. What happens is, those people can get closed-minded and see something new as a threat to their livelihood. But we need what this school offers as well as what district schools offer. We can’t afford to be narrow-minded.”

District officials might not want to acknowledge it, but Elevate Academy is already playing an important role in the community, Burkhart said. His company, which supplied the structural steel for the school building, will host interns and apprentices from Elevate.

“Kids can get out of high school and be kind of lost, and if they’re not headed for college, they can feel the only choices are gangs and drugs or a dead-end job,” Burkhart said. Elevate graduates will immediately be qualified for jobs at companies like Rule Steel, where in their first year out of high school, they can earn more than $40,000 and a full benefits package.

“It helps some kids avoid that period of panic when they get out of high school, and get them into jobs that make them feel good and productive and able to live the American Dream,” Burkhart said.

Forge International School

Crossing the boundaries that separate languages, countries and culture

As soon as he heard about the K-12 International Baccalaureate charter school opening just eight miles from his house, Ivan Sanchez knew he wanted his three oldest boys to go there. They had been attending a nearby Catholic school, which he and they loved, but Sanchez thought it was important to choose a school that would broaden their horizons.

“I felt they weren’t getting the stimulation of seeing the world outside their little bubble,” Sanchez said. “At Forge International School, the learning is really hands-on, and they are determined to have a very successful culture and a strong staff. My boys are going to enjoy this school and thrive in it.”

IB schools exist to help people cross the boundaries that separate languages, countries and culture. Their mission is to develop “active, compassionate and lifelong learners” by fostering a distinct set of attributes embodied in the internationally recognized IB learner profile.

Forge’s student body is more diverse than the community that surrounds it. Eighteen percent of the student population are racial or ethnic minorities, the vast majority of them (14 percent) Latino. The city of Middleton is 90 percent white, according to the most recent estimate from the U.S. Census, in 2017.

Micah Doramus, Forge’s head of school, grew up in the nearby town of Greenleaf (pop. 846). He was steeped in the IB philosophy during several years at Sage International, Forge’s Boise-based sister school, including three as principal. Sage has been in operation for more than a decade and enrolls more than 1,000 K-12 students while maintaining a 500-student waiting list. Sage is regularly one of Idaho’s highest-performing public schools. It annually ranks in the top 20 schools on the state assessments in both math and English Language Arts.

What will help Forge stand out from other schools in the area is its emphasis on project-based, hands-on learning, Doramus said. “IB is a framework that values inquiry-based learning that encourages kids to solve problems in the community around them.”

An IB school should be highly localized in its approach, Doramus said, noting that there are IB schools around the world, including in Israel and Arab countries. “You can’t get more diverse politically and culturally than a scenario like that,” he said.

While IB schools proliferate in more urban and coastal areas of the U.S., they’re relatively rare in the rural Mountain West. Forge is just the fifth school in Idaho with IB affiliation and, along with Sage, is the only public IB charter school. The board of Sage had long discussed opening an IB school in rural Middleton, 25 miles northwest of Boise. “The thought was to put both IB and charter education where none of that had previously existed,” Doramus said.

One reason for the scarcity of IB schools in Idaho might be the conspiracy-theorist take on IB that circulates on some far-right websites and talk shows. Doramus said he has seen websites that portray it as left-leaning, even communist, with a world government agenda. None of that is remotely true.

But those inaccurate portrayals made student recruitment in conservative Middleton challenging.

Still, when the school opened with kindergarten through fifth grade in early September, 264 of its 276 seats were filled. That’s because, Doramus said, plenty of parents were open-minded, and when they learned about the school’s approach to education, they were excited to enroll their kids.

Perhaps the main attraction for some families is that students start learning Spanish in kindergarten. “Families have been eager for their kids to have some of that cultural language exposure and diversity,” Doramus said.

A unique feature of Forge is that the classrooms, which Doramus calls learning spaces, belong to the students, not the teachers. This means that a kindergarten class will remain in the same physical space through third or fourth grade, and the teacher will move to a different classroom for the following year’s kindergarten class. The students get to decorate their space; they choose, to some extent, what goes on the walls and how the room is arranged.

“When kids come back to school from summer break, they come home to the same classroom they left in the spring. It feels like home, and it empowers the kids,” Doramus said.

Forge faced challenges prior to opening, and although the school is now open, it’s still an uphill climb. It had to delay its opening by three weeks because construction was behind schedule from the outset. The decision to delay the opening was made last December, giving parents plenty of time to plan their children’s school options.

Forge will also have to do intensive fundraising to finish the physical plant. The high school has yet to be built, and the school to date lacks a playground. But Doramus is optimistic that funding will fall into place.

“The community is very supportive of what we’re doing, offering an inclusive, empowering educational environment where kids feel it is safe to take risks in their learning,” Doramus said. “We want them to be curious, ask tough questions of the world around them, and challenge themselves to find answers to questions and solutions to problems.”

Treasure Valley Classical Academy

Engaging students in the highest matters and the deepest questions

Kim Piotrowski was homeschooling her then-fourth-grade daughter when she heard about the Treasure Valley Classical Academy that would be opening the following year in the hamlet of Fruitland.

Piotrowski was familiar with the Barney Charter School Initiative, which supports the launch of K-12 charter schools across the country. Barney is a program of the private Hillsdale College in Michigan. Founded in 1844 by abolitionists known as Free Will Baptists, it has a liberal arts curriculum based on the Western heritage as a product of both Greco-Roman culture and the Judeo-Christian tradition. Hillsdale requires every student, regardless of major, to complete a core curriculum that includes courses on the Great Books, the U.S. Constitution, biology, chemistry and physics. These same traditions and values animate the Barney Charter School Initiative and the work of its 24 public charter school partners across the country.

The Barney initiative’s website says its partner schools “will train the minds and improve the hearts of young people through a rigorous, classical education in the liberal arts and sciences, with instruction in the principles of moral character and civic virtue.”

That was right up Piotrowski’s alley. She was willing to stop homeschooling if she could get her daughter into Treasure Valley. There was just one problem: The family lives in the town of Marsing, Idaho, which is 40 miles south of Fruitland.

No problem. Piotrowski was so enthused about the school that she bought a house in Fruitland. Then she landed the job of receptionist at the school. She and her daughter return to Marsing on the weekends.

“I feel blessed on all sides,” she said. “My daughter loves the school, and so do I.”

Talk to any number of Treasure Valley parents, and one comes away with a similar sense of devotion to the school and its mission. That may be in part because Fruitland is nestled in a deeply conservative part of Idaho. Many of the parents had been homeschooling their children because they were wary of the values being imparted to their children by traditional public schools.

The classical academy opened this fall with 310 students in grades K-6. The school will add a grade each year until it’s K-12 and enrolling up to 702 students. Its inaugural student population is significantly more diverse than the town of Fruitland. Three-quarters of the school’s students are white, 11 percent are mixed race, and 5 percent are Latino. About 30 percent qualify for federally subsidized lunches, which is often used as a proxy for low-income status.

Its home is a long-vacant middle school in the heart of town. Built in 1928, the brick-and-masonry school building seems perfectly suited to house a school where students are immersed in a classical education. A $4.2 million renovation took longer than expected and forced the school to delay its August opening by a week.

Given its approach and philosophy, it might seem that Treasure Valley is designed for a small segment of society, but Piotrowski, as well as school principal Stephen Lambert, insist anyone can thrive in their school.

“This is good for all human beings. This is how human formation ought to happen,” said Lambert, who came to Fruitland after running another successful Barney charter school in Atlanta, and before that serving in the Air Force for a quarter-century, retiring as a colonel. “Our country needs this to develop citizens of virtue and knowledge. This education is empowering, and if you work hard at it, then you will have the choice to do anything you want with your life.”

The school’s Barney-designed curriculum is identical to that of Lambert’s prior school, Atlanta Classical Academy, which graduated its first class of seniors in 2019. All 34 of the Atlanta school’s graduating seniors were offered admission to postsecondary four-year institutions, many of them highly selective.

What, in Lambert’s view, is a classical education? It’s rigorous, it’s academic, and it’s broad, as opposed to the specialized offerings of many school programs these days.

Lambert is confident that many of his graduates will be admitted to highly selective colleges and universities. But, he stressed, that’s not the main objective of Treasure Valley Classical Academy. “This academic curriculum will prepare them to be very competitive. Is that our objective? No, it is not. Our objective is to build human beings; it is not to be a college factory.”

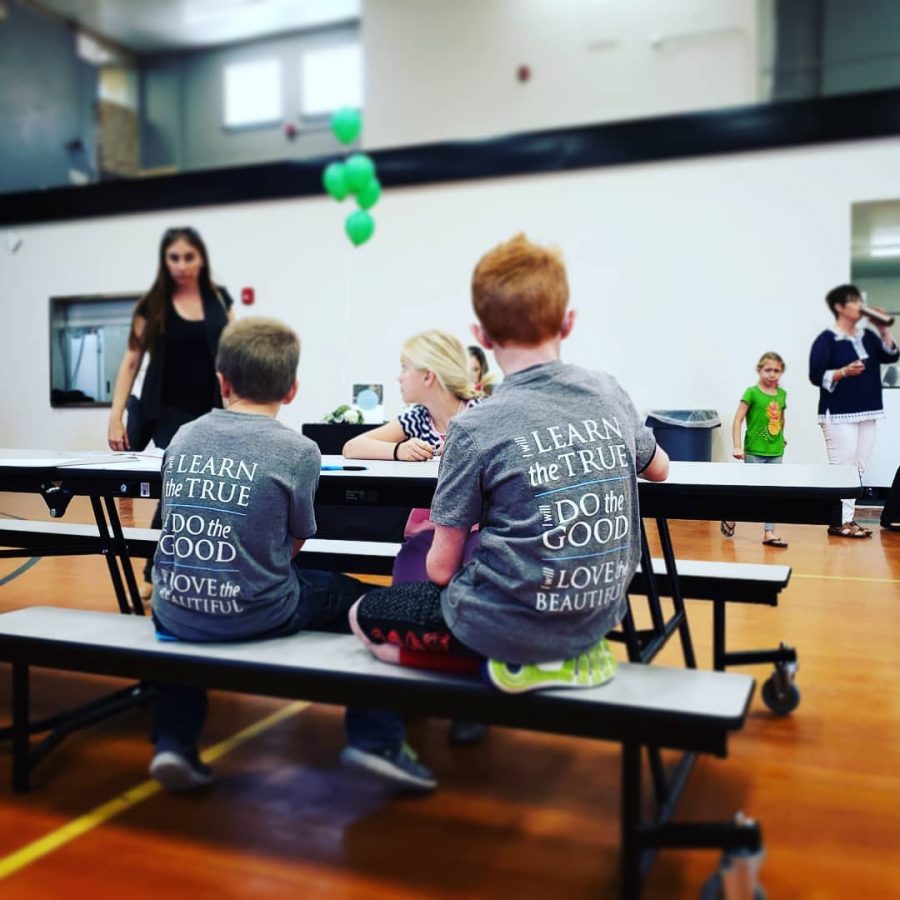

Walking the halls of the meticulously renovated building, with its high ceilings, wood floors and soaring banks of windows, feels in some ways like stepping into a time machine and going back 60 years. Students in uniforms (girls in plaid skirts and white blouses, boys in button-down or polo shirts and slacks) walk silently through the halls in straight lines. Classrooms — including kindergarten — feature individual desks in neat rows.

Inspirational quotations from historical figures festoon the hallways, and the school’s vision statement is prominently visible throughout the school:

Our vision is to form future citizens who uphold the ideals of our country’s founding and promoted the continuation of our American experiment — through a classical, great books curriculum designed to engage students in the highest matters and the deepest questions of truth, justice, virtue, and beauty.

Academically, the school focuses on great books in literature (fourth-graders were reading Robin Hood earlier this year; books like The Secret Garden and To Kill a Mockingbird stocked the shelves in the teacher resource room); primary source documents in history; “text-centered, teacher-led instruction fostering pre-Socratic inquiry and discussion”; Spanish, as well as Latin, for all seventh- through ninth-graders.

Parent Sheena Lankford has four children at the school: boys in sixth and third grade, girls in fifth and first grade. Like many Treasure Valley parents, she and her husband homeschooled their children before the school opened. She has not regretted the decision.

“It is important to us to build a good education, but even more important to us for them to have good character,” Lankford said. “This school really embodies that.”

Bluum CEO Terry Ryan said the three new schools his organization helped open are providing new, high-quality choices for students in more rural areas.

“We have an opportunity to help open schools that provide our families, children and communities with options for success that simply wouldn’t exist if it were not for the strategic growth and expansion of public charter schools like Elevate, Forge and Treasure Valley Classical Academy,” Ryan said. “We are proud to work with these schools and their leaders, and we feel privileged to work together to help move education forward in Idaho.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)